Brief biography of Otto von Bismarck - prince, politician, statesman, first Chancellor of the German Empire, who implemented the plan for the unification of Germany, called the “Iron Chancellor”.

Otto von Bismarck, full name Otto Eduard Leopold Karl-Wilhelm-Ferdinand Duke von Lauenburg Prince von Bismarck und Schönhausen (in German Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen)

Born on April 1, 1815 at Schönhausen Castle in the Brandenburg province. The Bismarck family belonged to the ancient nobility, descended from conquering knights (in Prussia they were called junkers). Otto spent his childhood on the family estate of Kniephof near Naugard, in Pomerania.

From 1822 to 1827, Bismarck was educated in Berlin, studying at the Plamann school, in which the main emphasis was on the development of physical abilities, and then continued his studies at the Frederick the Great gymnasium.

Otto's interests are expressed in the study of foreign languages, politics of past years, the history of military and peaceful confrontation between different countries. After graduating from high school, Otto entered the university. Studied law and jurisprudence in Göttingen, Berlin. Upon completion of his studies, Otto received a position in the Berlin Municipal Court, and there in Berlin he joined the Jaeger Regiment.  In 1838, having moved to Greifswald, Bismarck continued to carry out military service.

In 1838, having moved to Greifswald, Bismarck continued to carry out military service.

A year later, the death of his mother forces Bismarck to return to his “family nest.” In Pomerania, Otto begins to lead the life of a simple landowner. By working hard, he gains respect, raises the authority of the estate and increases his income. But due to his hot temper and violent disposition, his neighbors nicknamed him “mad Bismarck.”

Bismarck continues to educate himself by studying the works of Hegel, Kant, Spinoza, David Friedrich Strauss and Feuerbach. The life of a landowner began to tire Bismarck, and in order to unwind, he went traveling, visiting England and France.

After the death of his father, Bismarck inherited estates in Pomerania. In 1847 he married Johanna von Puttkamer.

On May 11, 1847, Bismarck had the first opportunity to enter politics as a deputy of the newly formed United Landtag of the Kingdom of Prussia.

From 1851 to 1959, Otto von Bismarck represented Prussia in the Federal Diet, which met in Frankfurt am Main.

from 1859 to 1862, Bismarck was Prussian ambassador to Russia, and in 1862 to France. Upon his return to Prussia, he becomes Minister-President and Minister of Foreign Affairs. The policy he pursued during these years was aimed at the unification of Germany and the rise of Prussia over all German lands. As a result of three victorious wars of Prussia: in 1864 together with Austria against Denmark, in 1866 against Austria, in 1870-1871 against France, the unification of the German lands was completed with “iron and blood”, and thus an influential state appeared - the German Empire. The most important consequence of the Austro-Prussian War was the formation in 1867 of the North German Confederation, for which Otto von Bismarck himself wrote the constitution. After the formation of the North German Confederation, Bismarck became Chancellor. On January 18, 1871, in the proclaimed German Empire, he received the highest government post of Imperial Chancellor, and, in accordance with the constitution of 1871, practically unlimited power.  With the help of a complex system of alliances: the alliance of three emperors - Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia in 1873 and 1881; Austro-German alliance 1879; Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy 1882; The Mediterranean Agreement of 1887 between Austria-Hungary, Italy and England and the “reinsurance treaty” with Russia of 1887 Bismarck managed to maintain peace in Europe.

With the help of a complex system of alliances: the alliance of three emperors - Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia in 1873 and 1881; Austro-German alliance 1879; Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy 1882; The Mediterranean Agreement of 1887 between Austria-Hungary, Italy and England and the “reinsurance treaty” with Russia of 1887 Bismarck managed to maintain peace in Europe.

In 1890, due to political differences with Emperor Wilhelm II, Bismarck resigned, receiving the honorary title of Duke and the rank of Colonel General of the Cavalry. But in politics, he continued to be a prominent figure as a member of the Reichstag.

Otto von Bismarck died on July 30, 1898 and was buried on his own estate in Friedrichsruhe, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. In Germany there are monuments to Otto von Bismorck; the most majestic was the 34-meter figure of Bismarck, which was constructed over 5 years according to the design of Hugo Lederer.

Section topic: Brief biography of Otto von Bismarck

Gorchakov's student

It is generally accepted that Bismarck's views as a diplomat were largely formed during his service in St. Petersburg under the influence of the Russian vice-chancellor Alexander Gorchakov. The future “Iron Chancellor” was not very happy with his appointment, taking it for exile.

Alexander Mikhailovich Gorchakov

Gorchakov prophesied a great future for Bismarck. Once, when he was already chancellor, he said, pointing to Bismarck: “Look at this man! Under Frederick the Great he could have become his minister.” In Russia, Bismarck studied the Russian language, spoke it very well and understood the essence of the characteristic Russian way of thinking, which greatly helped him in the future in choosing the right political line in relation to Russia.

He took part in the Russian royal pastime - bear hunting, and even killed two bears, but stopped this activity, declaring that it was dishonorable to take a gun against unarmed animals. During one of these hunts, his legs were so severely frostbitten that there was a question of amputation.

Russian love

Twenty-two-year-old Ekaterina Orlova-Trubetskaya

At the French resort of Biarritz, Bismarck met the 22-year-old wife of the Russian Ambassador to Belgium, Ekaterina Orlova-Trubetskoy. A week in her company almost drove Bismarck crazy. Catherine's husband, Prince Orlov, could not take part in his wife's festivities and bathing, as he was wounded in the Crimean War. But Bismarck could. Once she and Catherine almost drowned. They were rescued by the lighthouse keeper. On this day, Bismarck would write to his wife: “After several hours of rest and writing letters to Paris and Berlin, I took a second sip of salt water, this time in the harbor when there were no waves. Swimming and diving a lot, dipping into the surf twice would be too much for one day.” This incident became, as it were, a divine hint so that the future chancellor would not cheat on his wife again. Soon there was no time left for betrayal - Bismarck would be swallowed up by politics.

Ems dispatch

In achieving his goals, Bismarck did not disdain anything, even falsification. In a tense situation, when the throne became vacant in Spain after the revolution in 1870, William I’s nephew Leopold began to lay claim to it. The Spaniards themselves called the Prussian prince to the throne, but France intervened in the matter, which could not allow such an important throne to be occupied by a Prussian. Bismarck made a lot of efforts to bring the matter to war. However, he was first convinced of Prussia’s readiness to enter the war.

Battle of Mars-la-Tour

To push Napoleon III into conflict, Bismarck decided to use the dispatch sent from Ems to provoke France. He changed the text of the message, shortening it and giving it a harsher tone that was insulting to France. In the new text of the dispatch, falsified by Bismarck, the end was composed as follows: “His Majesty the King then refused to receive the French ambassador again and ordered the adjutant on duty to tell him that His Majesty had nothing more to say.” This text, offensive to France, was transmitted by Bismarck to the press and to all Prussian missions abroad and the next day became known in Paris. As Bismarck expected, Napoleon III immediately declared war on Prussia, which ended in the defeat of France.

Caricature from Punch magazine. Bismarck manipulates Russia, Austria and Germany

"Nothing"

Bismarck continued to use Russian throughout his political career. Russian words slip into his letters every now and then. Having already become the head of the Prussian government, he even sometimes made resolutions on official documents in Russian: “Impossible” or “Caution.” But the Russian “nothing” became the favorite word of the “Iron Chancellor”. He admired its nuance and polysemy and often used it in private correspondence, for example: “Alles nothing.”

Resignation. The new Emperor Wilhelm II looks down from above

An incident helped Bismarck to understand this word. Bismarck hired a coachman, but doubted that his horses could go fast enough. "Nothing!" - answered the driver and rushed along the uneven road so briskly that Bismarck became worried: “You won’t throw me out?” "Nothing!" - answered the coachman. The sleigh overturned, and Bismarck flew into the snow, bleeding his face. In a rage, he swung a steel cane at the driver, and he grabbed a handful of snow with his hands to wipe Bismarck’s bloody face, and kept saying: “Nothing... nothing!” Subsequently, Bismarck ordered a ring from this cane with the inscription in Latin letters: “Nothing!” And he admitted that in difficult moments he felt relief, telling himself in Russian: “Nothing!”

![]()

Otto Eduard Leopold Karl-Wilhelm-Ferdinand Duke von Lauenburg Prince von Bismarck und Schönhausen(German) Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen ; April 1, 1815 - July 30, 1898) - prince, politician, statesman, first Chancellor of the German Empire (Second Reich), nicknamed the "Iron Chancellor". He had the honorary rank (peacetime) of Prussian Colonel General with the rank of Field Marshal (March 20, 1890).

While serving as Reich Chancellor and Prussian Minister-Chairman, he had significant influence on the policies of the created Reich until his resignation in the city. In foreign policy, Bismarck adhered to the principle of the balance of power (or European balance, see Bismarck's alliance system)

In domestic politics, the time of his reign from the city can be divided into two phases. At first he made an alliance with moderate liberals. Numerous domestic reforms took place during this period, such as the introduction of civil marriage, which was used by Bismarck to weaken the influence of the Catholic Church (see Kulturkampf). Beginning in the late 1870s, Bismarck separated from the liberals. During this phase, he resorts to policies of protectionism and government intervention in the economy. In the 1880s, an anti-socialist law was introduced. Disagreements with the then Kaiser Wilhelm II led to Bismarck's resignation.

In subsequent years, Bismarck played a prominent political role, criticizing his successors. Thanks to the popularity of his memoirs, Bismarck managed to influence the formation of his own image in the public consciousness for a long time.

By the middle of the 20th century, German historical literature was dominated by an unconditionally positive assessment of the role of Bismarck as a politician responsible for uniting the German principalities into a single national state, which partially satisfied national interests. After his death, numerous monuments were erected in his honor as a symbol of strong personal power. He created a new nation and implemented progressive social welfare systems. Bismarck, being loyal to the king, strengthened the state with a strong, well-trained bureaucracy. After World War II, critical voices began to sound louder, accusing Bismarck, in particular, of curtailing democracy in Germany. More attention was paid to the shortcomings of his policies, and the activities were considered in the current context.

Biography

Origin

Otto von Bismarck was born on April 1, 1815 into a family of small landed nobles in the Brandenburg province (now Saxony-Anhalt). All generations of the Bismarck family served the rulers in peaceful and military fields, but did not show themselves to be anything special. Simply put, the Bismarcks were junkers - descendants of conquering knights who founded settlements in the lands east of the Elbe River. The Bismarcks could not boast of extensive landholdings, wealth or aristocratic luxury, but were considered noble.

Youth

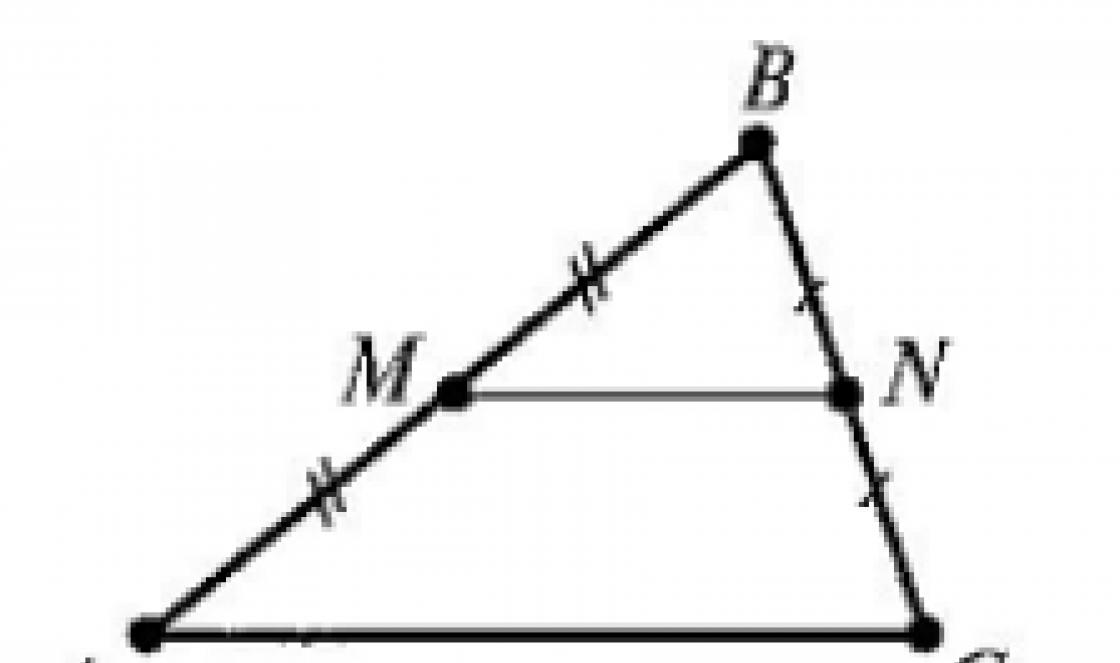

With iron and blood

The regent under the incompetent King Frederick William IV, Prince Wilhelm, closely associated with the army, was extremely dissatisfied with the existence of the Landwehr - a territorial army that played a decisive role in the fight against Napoleon and maintained liberal sentiments. Moreover, the Landwehr, relatively independent of the government, proved ineffective in suppressing the 1848 revolution. Therefore, he supported the Prussian Minister of War Roon in developing a military reform that envisaged the creation of a regular army with service life in the infantry increased to 3 years and four years in the cavalry. Military spending was supposed to increase by 25%. This met with resistance, and the king dissolved the liberal government, replacing it with a reactionary administration. But the budget was again not approved.

At this time, European trade was actively developing, in which Prussia played an important role with its rapidly developing industry, an obstacle to which was Austria, which practiced a protectionist position. To inflict moral damage on her, Prussia recognized the legitimacy of the Italian king Victor Emmanuel, who came to power in the wake of the revolution against the Habsburgs.

Annexation of Schleswig and Holstein

Bismarck is a triumphant man.

Creation of the North German Confederation

The fight against the Catholic opposition

Bismarck and Lasker in Parliament

The unification of Germany led to the fact that communities that were once in violent conflict with each other found themselves in one state. One of the most important problems facing the newly created empire was the question of interaction between the state and the Catholic Church. On this basis it began Kulturkampf- Bismarck's struggle for the cultural unification of Germany.

Bismarck and Windthorst

Bismarck met the liberals halfway in order to ensure their support for his course, agreed with the proposed changes in civil and criminal legislation and ensuring freedom of speech, which did not always correspond to his wishes. However, all this led to the strengthening of the influence of centrists and conservatives, who began to view the attack against the church as a manifestation of godless liberalism. As a result, Bismarck himself began to view his campaign as a serious mistake.

The long struggle with Arnim and the irreconcilable resistance of Windthorst's centrist party could not but affect the health and morale of the chancellor.

Strengthening peace in Europe

Introductory quote to the exhibition of the Bavarian War Museum. Ingolstadt

We do not need war, we belong to what the old Prince Metternich had in mind, namely, to a state completely satisfied with its position, which can defend itself if necessary. And, besides, even if this becomes necessary, do not forget about our peaceful initiatives. And I declare this not only in the Reichstag, but especially to the whole world, that this has been the policy of Kaiser Germany for the past sixteen years.

Soon after the creation of the Second Reich, Bismarck became convinced that Germany did not have the ability to dominate Europe. He failed to realize the hundreds of years old idea of uniting all Germans in a single state. This was prevented by Austria, which was striving for the same thing, but only under the condition of the leading role in this state of the Habsburg dynasty.

Fearing French revenge in the future, Bismarck sought rapprochement with Russia. On March 13, 1871, he, together with representatives of Russia and other countries, signed the London Convention, which lifted the ban on Russia to have a navy in the Black Sea. In 1872, Bismarck and Gorchakov (with whom Bismarck had a personal relationship, like a talented student with his teacher), organized a meeting in Berlin of three emperors - German, Austrian and Russian. They came to an agreement to jointly confront the revolutionary danger. After that, Bismarck had a conflict with the German Ambassador to France, Arnim, who, like Bismarck, belonged to the conservative wing, which alienated the Chancellor from the conservative Junkers. The result of this confrontation was the arrest of Arnim under the pretext of improper handling of documents.

Bismarck, taking into account Germany's central position in Europe and the associated real danger of being involved in a war on two fronts, created a formula that he followed throughout his reign: “A strong Germany strives to live in peace and develop peacefully.” To this end, she must have a strong army so as not to be attacked by anyone who draws the sword from its scabbard.

Throughout his service, Bismarck experienced the “nightmare of coalitions” (le cauchemar des coalitions), and, figuratively speaking, tried unsuccessfully to juggle five balls in the air.

Now Bismarck could hope that England would concentrate on the problem of Egypt, which arose after France bought up shares in the Suez Canal, and Russia became involved in solving the Black Sea problems, and therefore the danger of creating an anti-German coalition was significantly reduced. Moreover, the rivalry between Austria and Russia in the Balkans meant that Russia needed German support. Thus, a situation was created in which all significant forces in Europe, with the exception of France, would not be able to create dangerous coalitions, being involved in mutual rivalry.

At the same time, this created a need for Russia to avoid aggravation of the international situation and it was forced to lose some of the benefits of its victory at the London negotiations, which were expressed at the congress that opened on June 13 in Berlin. The Berlin Congress was created to consider the results of the Russian-Turkish war, which was chaired by Bismarck. The Congress turned out to be surprisingly effective, although Bismarck had to constantly maneuver between representatives of all the great powers. On July 13, 1878, Bismarck signed the Treaty of Berlin with representatives of the great powers, which established new borders in Europe. Then many of the territories transferred to Russia were returned to Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina were transferred to Austria, and the Turkish Sultan, filled with gratitude, gave Cyprus to Britain.

After this, a sharp pan-Slavist campaign against Germany began in the Russian press. The coalition nightmare arose again. On the verge of panic, Bismarck invited Austria to conclude a customs agreement, and when she refused, even a mutual non-aggression treaty. Emperor Wilhelm I was frightened by the end of the previous pro-Russian orientation of German foreign policy and warned Bismarck that things were moving toward an alliance between Tsarist Russia and France, which had become a republic again. At the same time, he pointed out the unreliability of Austria as an ally, which could not deal with its internal problems, as well as the uncertainty of Britain’s position.

Bismarck tried to justify his line by pointing out that his initiatives were taken in the interests of Russia. On October 7, he concluded a “Dual Alliance” with Austria, which pushed Russia into an alliance with France. This was Bismarck's fatal mistake, destroying the close relations between Russia and Germany that had been established since the German War of Liberation. A tough tariff struggle began between Russia and Germany. From that time on, the General Staffs of both countries began to develop plans for a preventive war against each other.

According to this treaty, Austria and Germany were supposed to jointly repel the Russian attack. If Germany were attacked by France, Austria pledged to remain neutral. It quickly became clear to Bismarck that this defensive alliance would immediately turn into offensive action, especially if Austria was on the verge of defeat.

However, Bismarck still managed to confirm an agreement with Russia on June 18, according to which the latter pledged to maintain neutrality in the event of a Franco-German war. But nothing was said about the relationship in the event of an Austro-Russian conflict. However, Bismarck demonstrated an understanding of Russia's claims to the Bosporus and Dardanelles in the hope that this would lead to conflict with Britain. Bismarck's supporters viewed this move as further proof of Bismarck's diplomatic genius. However, the future showed that this was only a temporary measure in an attempt to avoid an impending international crisis.

Bismarck proceeded from his belief that stability in Europe could be achieved only if England joined the “Mutual Treaty”. In 1889, he approached Lord Salisbury with a proposal to conclude a military alliance, but the lord categorically refused. Although Britain was interested in resolving the colonial problem with Germany, it did not want to bind itself to any obligations in central Europe, where the potentially hostile states of France and Russia were located. Bismarck’s hopes that the contradictions between England and Russia would contribute to its rapprochement with the countries of the “Mutual Treaty” were not confirmed.

Danger on the left

“As long as it’s stormy, I’m at the helm”

To the 60th anniversary of the Chancellor

In addition to the external danger, the internal danger became increasingly stronger, namely the socialist movement in the industrial regions. To combat it, Bismarck tried to pass new repressive legislation. Bismarck spoke more and more often about the “Red Menace,” especially after the assassination attempt on the emperor.

Colonial policy

At certain points he showed commitment to the colonial issue, but this was a political move, for example during the election campaign of 1884, when he was accused of lack of patriotism. In addition, this was done in order to reduce the chances of the heir prince Frederick with his leftist views and far-reaching pro-English orientation. In addition, he understood that the key problem for the country's security was normal relations with England. In 1890, he exchanged Zanzibar from England for the island of Heligoland, which much later became an outpost of the German fleet in the world's oceans.

Otto von Bismarck managed to involve his son Herbert in colonial affairs, who was involved in resolving issues with England. But there were also enough problems with his son - he inherited only bad traits from his father and was a drunkard.

Resignation

Bismarck tried not only to influence the formation of his image in the eyes of his descendants, but also continued to interfere in contemporary politics, in particular, he undertook active campaigns in the press. Bismarck was most often attacked by his successor, Caprivi. Indirectly, he criticized the emperor, whom he could not forgive for his resignation. In the summer, Mr. Bismarck took part in the elections to the Reichstag, however, he never took part in the work of his 19th constituency in Hanover, never used his mandate, and in 1893. resigned

The press campaign was successful. Public opinion swung in favor of Bismarck, especially after Wilhelm II began to openly attack him. The authority of the new Reich Chancellor Caprivi suffered especially badly when he tried to prevent Bismarck from meeting with the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph. The journey to Vienna turned into a triumph for Bismarck, who declared that he had no responsibilities to the German authorities: “all bridges were burned”

Wilhelm II was forced to accept reconciliation. Several meetings with Bismarck in the city went well, but did not lead to real detente in relations. Just how unpopular Bismarck was in the Reichstag was shown by the fierce battles over the approval of congratulations on the occasion of his 80th birthday. Due to the publication in 1896. The top-secret reinsurance agreement attracted the attention of the German and foreign press.

Memory

Historiography

In the more than 150 years since Bismarck's birth, many different interpretations of his personal and political activities have arisen, some of them mutually contradictory. Until the end of World War II, German-language literature was dominated by writers whose point of view was influenced by their own political and religious worldview. Historian Karina Urbach noted in the city: “His biography was taught to at least six generations, and it is safe to say that each subsequent generation studied a different Bismarck. No other German politician has been used and distorted as much as he."

Empire times

Controversies surrounding the figure of Bismarck existed even during his lifetime. Already in the first biographical publications, sometimes multi-volume, the complexity and ambiguity of Bismarck was emphasized. Sociologist Max Weber critically assessed Bismarck's role in the process of German unification: “The work of his life was not only the external, but also the internal unity of the nation, but each of us knows: this was not achieved. This cannot be achieved using his methods." Theodor Fontane, in the last years of his life, painted a literary portrait in which he compared Bismarck with Wallenstein. The assessment of Bismarck from Fontane's point of view differs significantly from the assessment of most contemporaries: “he is a great genius, but a small man.”

A negative assessment of Bismarck's role did not find support for a long time, partly thanks to his memoirs. They became an almost inexhaustible source of quotes for his fans. For decades, the book formed the basis of the image of Bismarck among patriotic citizens. At the same time, it weakened the critical view of the founder of the empire. During his lifetime, Bismarck had personal influence over his image in history, as he controlled access to documents and sometimes corrected manuscripts. After the death of the chancellor, control over the formation of the image in history was taken over by his son, Herbert von Bismarck.

Professional historical science could not get rid of the influence of Bismarck's role in the unification of the German lands and joined in the idealization of his image. Heinrich von Treitschke changed his attitude towards Bismarck from critical to devoted admirer. He called the founding of the German Empire the most striking example of heroism in German history. Treitschke and other representatives of the Lesser German-Borussian school of history were fascinated by Bismarck's strength of character. Bismarck biographer Erich Marx wrote in 1906: “In fact, I must admit: living in those times was such a great experience that everything that has to do with it is of value for history.” However, Marx, along with other Wilhelmian historians such as Heinrich von Siebel, noted the contradictory nature of Bismarck's role in comparison with the achievements of the Hohenzollerns. So, in 1914. in school textbooks, it was not Bismarck, Wilhelm I, who was called the founder of the German Empire.

A decisive contribution to the exaltation of Bismarck's role in history was made in the First World War. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Bismarck in 1915. articles were published that did not even hide their propaganda purpose. In a patriotic impulse, historians noted the duties of German soldiers to defend the unity and greatness of Germany achieved by Bismarck from foreign invaders, and at the same time, remained silent about Bismarck’s numerous warnings about the inadmissibility of such a war in the middle of Europe. Bismarck scholars such as Erich Marx, Mack Lenz and Horst Kohl have portrayed Bismarck as a conduit for the German warrior spirit.

Weimar Republic and Third Reich

Germany's defeat in the war and the creation of the Weimar Republic did not change Bismarck's idealistic image, since the elite historians remained loyal to the monarch. In such a helpless and chaotic state, Bismarck was like a guide, a father, a genius to be followed in order to end the “Versailles humiliation.” If any criticism of his role in history was expressed, it concerned the Little German way of solving the German question, and not the military or imposed unification of the state. Traditionalism prevented the emergence of innovative biographies of Bismarck. The publication of further documents in the 1920s once again helped to emphasize Bismarck's diplomatic skill. The most popular biography of Bismarck at the time was written by Mr. Emil Ludwig, which presented a critical psychological analysis of how Bismarck was portrayed as a Faustian hero in the 19th century historical drama.

During the Nazi period, a historical lineage between Bismarck and Adolf Hitler was more often depicted in order to secure the Third Reich's leading role in the German unity movement. Erich Marx, a pioneer of Bismarck studies, emphasized these ideologically driven historical interpretations. In Britain, Bismarck was also portrayed as the predecessor of Hitler, who stood at the beginning of Germany's special path. As World War II progressed, Bismarck's weight in propaganda decreased somewhat; Since then, his warning about the inadmissibility of war with Russia has not been mentioned. But conservative representatives of the resistance movement saw their guide in Bismarck

An important critical work was published by the German lawyer in exile Erich Eick, who wrote a biography of Bismarck in three volumes. He criticized Bismarck for his cynical attitude towards democratic, liberal and humanistic values and held him responsible for the destruction of democracy in Germany. The system of unions was very cleverly constructed, but, being an artificial construction, it was doomed to collapse from birth. However, Eick could not help but admire the figure of Bismarck: “but no one, anywhere, can disagree with the fact that he [Bismarck] was the main figure of his time... No one can help but admire the power of the charm of this man, who is always curious and important."

Post-war period until 1990

After World War II, influential German historians, notably Hans Rothfelds and Theodor Schieder, took a varied but positive view of Bismarck. Friedrich Meinecke, a former admirer of Bismarck, argued in 1946. in the book “The German Disaster” (German. Die deutsche Katastrophe) that the painful defeat of the German nation-state canceled out all praise of Bismarck for the foreseeable future.

Briton Alan J.P. Taylor made it public in 1955. a psychological, and not least because of this limited, biography of Bismarck, in which he tried to show the struggle between the paternal and maternal principles in the soul of his hero. Taylor positively characterized Bismarck's instinctive struggle for order in Europe with the aggressive foreign policy of the Wilhelminian era. The first post-war biography of Bismarck, written by Wilhelm Momsen, differed from the works of his predecessors in a style that pretended to be sober and objective. Momsen emphasized Bismarck's political flexibility, and believed that his failures could not overshadow the successes of government.

In the late 1970s, a movement of social historians against biographical research emerged. Since then, biographies of Bismarck have begun to appear, in which he is depicted either in extremely light or dark colors. A common feature of most new biographies of Bismarck is an attempt to synthesize Bismarck's influence and describe his position in the social structures and political processes of the time

The American historian Otto Pflanze released between and. a multi-volume biography of Bismarck, in which, unlike others, Bismarck’s personality was placed in the foreground, studied by means of psychoanalysis. Pflanze criticized Bismarck for his treatment of political parties and subordination of the constitution to his own purposes, which set a negative precedent to follow. According to Pflanz, the image of Bismarck as the unifier of the German nation comes from Bismarck himself, who from the very beginning sought only to strengthen Prussian power over the major states of Europe.

Phrases attributed to Bismarck

- By providence itself I was destined to be a diplomat: after all, I was even born on the first of April.

- Revolutions are conceived by geniuses, carried out by fanatics, and their results are used by scoundrels.

- People never lie so much as after a hunt, during a war and before elections.

- Don't expect that once you take advantage of Russia's weakness, you will receive dividends forever. Russians always come for their money. And when they come, do not rely on the Jesuit agreements you signed, which supposedly justify you. They are not worth the paper they are written on. Therefore, you should either play fairly with the Russians, or not play at all.

- The Russians take a long time to harness, but they travel quickly.

- Congratulate me - the comedy is over... (while leaving the post of chancellor).

- As always, he has a prima donna smile on his lips and an ice compress on his heart (about the Chancellor of the Russian Empire Gorchakov).

- You don't know this audience! Finally, the Jew Rothschild... this, I tell you, is an incomparable brute. For the sake of speculation on the stock exchange, he is ready to bury all of Europe, and it’s… me who’s to blame?

- There will always be someone who doesn't like what you do. This is fine. Everyone only likes kittens.

- Before his death, having briefly regained consciousness, he said: “I am dying, but from the point of view of the interests of the state, this is impossible!”

- The war between Germany and Russia is the greatest stupidity. That is why it will definitely happen.

- Study as if you were to live forever, live as if you were to die tomorrow.

- Even the most favorable outcome of the war will never lead to the disintegration of the main strength of Russia, which is based on millions of Russians... These latter, even if they are dismembered by international treatises, are just as quickly reunited with each other, like particles of a cut piece of mercury...

- The great questions of the time are not decided by the decisions of the majority, but only by iron and blood!

- Woe to the statesman who does not take the trouble to find a basis for war that will still retain its significance even after the war.

- Even a victorious war is an evil that must be prevented by the wisdom of nations.

- Revolutions are prepared by geniuses, carried out by romantics, and their fruits are enjoyed by scoundrels.

- Russia is dangerous due to the meagerness of its needs.

- A preventive war against Russia is suicide due to fear of death.

Gallery

see also

Notes

- Richard Carstensen / Bismarck anekdotisches.Muenchen:Bechtle Verlag. 1981. ISBN 3-7628-0406-0

- Martin Kitchen. The Cambridge Illustrated History of Germany:-Cambridge University Press 1996 ISBN 0-521-45341-0

- Nachum T.Gidal:Die Juden in Deutschland von der Römerzeit bis zur Weimarer Republik. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Lexikon Verlag 1988. ISBN 3-89508-540-5

- Showing the significant role of Bismarck in European history, the author of the cartoon is mistaken regarding Russia, which in those years pursued a policy independent of Germany.

- “Aber das kann man nicht von mir verlangen, dass ich, nachdem ich vierzig Jahre lang Politik getrieben, plötzlich mich gar nicht mehr damit abgeben soll.” Zit. nach Ullrich: Bismarck. S. 122.

- Ullrich: Bismarck. S. 7 f.

- Alfred Vagts: Diederich Hahn - Ein Politikerleben. In: Jahrbuch der Männer vom Morgenstern. Band 46, Bremerhaven 1965, S. 161 f.

- "Alle Brücken sind abgebrochen."Volker Ullrich: Otto von Bismarck. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-499-50602-5, S. 124.

- Ullrich: Bismarck. S. 122-128.

- Reinhard Pözorny(Hg) Deutsches National-Lexikon-DSZ-Verlag. 1992. ISBN 3-925924-09-4

- In the original: English. „His life has been taught to at least six generations, and one can fairly say that almost every second German generation has encountered another version of Bismarck. No other German political figure has been as used and abused for political purposes.” Div.: Karina Urbach, Between Saviour and Villain. 100 Years of Bismarck Biographies,in: The Historical Journal. Jg. 41, Nr. 4, December 1998, art. 1141-1160 (1142).

- Georg Hesekiel: Das Buch vom Grafen Bismarck. Velhagen & Klasing, Bielefeld 1869; Ludwig Hahn: Fürst von Bismarck. Sein politisches Leben und Wirken. 5 Bd. Hertz, Berlin 1878-1891; Hermann Jahnke: Fürst Bismarck, sein Leben und Wirken. Kittel, Berlin 1890; Hans Bloom: Bismarck und seine Zeit. Eine Biographie für das deutsche Volk. 6 Bd. mit Reg-Bd. Beck, Munich 1894-1899.

- “Denn dieses Lebenswerk hätte doch nicht nur zur äußeren, sondern auch zur inneren Einigung der Nation führen sollen und jeder von uns weiß: das ist nicht erreicht. Es konnte mit seinen Mitteln nicht erreicht werden.” Zit. n. Volker Ullrich: Die nervöse Großmacht. Aufstieg und Untergang des deutschen Kaiserreichs. 6. Aufl. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 978-3-596-11694-2, S. 29.

- Theodore Fontane: Der Zivil-Wallenstein. In: Gotthard Erler (Hrsg.): Kahlebutz und Krautentochter. Märkische Portraits. Aufbau Taschenbuch Verlag, Berlin 2007,

The collector of German lands, the “Iron Chancellor” Otto von Bismarck, was a great German politician and diplomat. The unification of Germany in 1871 was completed with his tears, sweat and blood.

In 1871, Otto von Bismarck became the first Chancellor of the German Empire. Under his leadership, Germany was unified through a “revolution from above.”

This was a man who loved to drink, eat well, fight duels in his spare time, and make a couple of good fights. For some time, the Iron Chancellor served as Prussia's ambassador to Russia. During this time, he fell in love with our country, but he really didn’t like expensive firewood, and in general he was a miser...

Here are Bismarck's most famous quotes about Russia:

The Russians take a long time to harness, but they travel quickly.

Don't expect that once you take advantage of Russia's weakness, you will receive dividends forever. Russians always come for their money. And when they come, do not rely on the Jesuit agreements you signed, which supposedly justify you. They are not worth the paper they are written on. Therefore, you should either play fairly with the Russians, or not play at all.

Even the most favorable outcome of the war will never lead to the disintegration of Russia's main strength. The Russians, even if they are dismembered by international treatises, will just as quickly reunite with each other, like particles of a cut piece of mercury. This is the indestructible state of the Russian nation, strong with its climate, its spaces and limited needs.

It is easier to defeat ten French armies, he said, than to understand the difference between perfect and imperfect verbs.

You should either play fairly with the Russians or not play at all.

A preventive war against Russia is suicide due to fear of death.

Presumably: If you want to build socialism, choose a country that you don’t mind.

“The power of Russia can only be undermined by the separation of Ukraine from it... it is necessary not only to tear off, but also to contrast Ukraine with Russia. To do this, you just need to find and cultivate traitors among the elite and, with their help, change the self-awareness of one part of the great people to such an extent that they will hate everything Russian, hate their family, without realizing it. Everything else is a matter of time.”

Of course, the great Chancellor of Germany was not describing today, but it is difficult to deny his insight. The European Union must stand on the borders with Russia. By any means. This is an important part of the strategy. It is not for nothing that the United States was so sensitive to these desperate vacillations of the Ukrainian leadership. Brussels has entered into this, its first significant geopolitical battle.

Never plot anything against Russia, because it will respond to every cunning of yours with its unpredictable stupidity.

This interpretation, more expanded, is common in RuNet.

Never plot anything against Russia - they will find their own stupidity for any of our cunning.

The Slavs cannot be defeated, we have been convinced of this for hundreds of years.

This is the indestructible state of the Russian nation, strong with its climate, its spaces and limited needs.

Even the most favorable outcome of an open war will never lead to the disintegration of the main strength of Russia, which is based on millions of Russians themselves...

Reich Chancellor Prince von Bismarck to Ambassador in Vienna Prince Henry VII Reuss

Confidentially

No. 349 Confidential (secret) Berlin 05/03/1888

After the arrival of the expected report No. 217 of the 28th of last month, Count Kalnoki has a tinge of doubt that the officers of the General Staff, who assumed the outbreak of war in the fall, may still be wrong.

One could argue on this topic if such a war would possibly lead to such consequences that Russia, in the words of Count Kalnoki, “will be defeated.” However, such a development of events, even with brilliant victories, is unlikely.

Even the most successful outcome of the war will never lead to the collapse of Russia, which rests on millions of Russian believers of the Greek faith.

These latter, even if they are subsequently corroded by international treaties, will reconnect with each other as quickly as separated droplets of mercury find their way to each other.

This is the indestructible State of the Russian nation, strong in its climate, its spaces and its unpretentiousness, as well as through the awareness of the need to constantly protect its borders. This State, even after complete defeat, will remain our creation, an enemy seeking revenge, as we have in the case of France today in the West. This would create a situation of constant tension for the future, which we would be forced to take upon ourselves if Russia decides to attack us or Austria. But I am not ready to take on this responsibility and be the initiator of creating such a situation ourselves.

We already have a failed example of the “Destruction” of a nation by three strong opponents,a much weaker Poland. This destruction failed for a full 100 years.

The vitality of the Russian nation will be no less; we will, in my opinion, have greater success if we simply treat them as an existing, constant danger against which we can create and maintain protective barriers. But we will never be able to eliminate the very existence of this danger.

By attacking today's Russia, we will only strengthen its desire for unity; waiting for Russia to attack us can lead to the fact that we will wait for its internal disintegration before it attacks us, and moreover, we can wait for this, the less we stop it from sliding into a dead end through threats.

f. Bismarck.

All the activities of the outstanding German politician, the “Iron Chancellor” Otto von Bismarck, were closely connected with Russia.

A book was published in Germany “Bismarck. Magician of Power”, Propylaea, Berlin 2013 under authorship Bismarck biographer Jonathan Steinberg.

The popular science 750-page tome entered the list of German bestsellers. There is enormous interest in Otto von Bismarck in Germany. Bismarck stayed in Russia as the Prussian envoy for almost three years, and his diplomatic activities were closely connected with Russia all his life. His statements about Russia are widely known - not always unambiguous, but most often benevolent.

In January 1859, the king's brother Wilhelm, who was then regent, sent Bismarck as envoy to St. Petersburg. For other Prussian diplomats this appointment would have been a promotion, but Bismarck took it as an exile. The priorities of Prussian foreign policy did not coincide with Bismarck’s beliefs, and he was removed from the court further, sending him to Russia. Bismarck had the diplomatic qualities necessary for this post. He had natural intelligence and political insight.

In Russia they treated him favorably. Since during the Crimean War, Bismarck opposed Austrian attempts to mobilize German armies for war with Russia and became the main supporter of an alliance with Russia and France, who had recently fought with each other. The alliance was directed against Austria.

In addition, he was favored by the Empress Dowager, née Princess Charlotte of Prussia. Bismarck was the only foreign diplomat who communicated closely with the royal family.

Another reason for his popularity and success: Bismarck spoke Russian well. He began to learn the language as soon as he learned about his new assignment. At first I studied on my own, and then I hired a tutor, law student Vladimir Alekseev. And Alekseev left his memories of Bismarck.

Bismarck had a fantastic memory. After just four months of studying Russian, Otto von Bismarck could already communicate in Russian. Bismarck initially hid his knowledge of the Russian language and this gave him an advantage. But one day the tsar was talking with Foreign Minister Gorchakov and caught Bismarck’s eye. Alexander II asked Bismarck head-on: “Do you understand Russian?” Bismarck confessed, and the Tsar was amazed at how quickly Bismarck mastered the Russian language and gave him a bunch of compliments.

Bismarck became close to the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Prince A.M. Gorchakov, who assisted Bismarck in his efforts aimed at diplomatic isolation of first Austria and then France.

It is believed that Bismarck’s communication with Alexander Mikhailovich Gorchakov, an outstanding statesman and Chancellor of the Russian Empire, played a decisive role in the formation of Bismarck’s future policy.

Gorchakov predicted a great future for Bismarck. Once, when he was already chancellor, he said, pointing to Bismarck: “Look at this man! Under Frederick the Great he could have become his minister.” Bismarck studied the Russian language well and spoke very decently, and understood the essence of the characteristic Russian way of thinking, which greatly helped him in the future in choosing the right political line in relation to Russia.

However, the author believes that Gorchakov’s diplomatic style was alien to Bismarck, who had the main goal of creating a strong, united Germany. TO when the interests of Prussia diverged from the interests of Russia, Bismarck confidently defended Prussia's positions. After the Berlin Congress, Bismarck broke up with Gorchakov.Bismarck more than once inflicted sensitive defeats on Gorchakov in the diplomatic arena, in particular at the Berlin Congress of 1878. And more than once he spoke negatively and disparagingly about Gorchakov.He had much more respect forGeneral of the Cavalry and Russian Ambassador to Great BritainPyotr Andreevich Shuvalov,

Bismarck wanted to be aware of both the political and social life of Russia, so I read Russian bestsellers, including Turgenev’s novel “The Noble Nest” and Herzen’s “The Bell,” which was banned in Russia.Thus, Bismarck not only learned the language, but also became familiar with the cultural and political context of Russian society, which gave him undeniable advantages in his diplomatic career.

He took part in the Russian royal sport - bear hunting, and even killed two, but stopped this activity, declaring that it was dishonorable to take a gun against unarmed animals. During one of these hunts, his legs were so severely frostbitten that there was a question of amputation.

Stately, representative,two meters tall andwith a bushy mustache, a 44-year-old Prussian diplomatenjoyed great success with“very beautiful” Russian ladies.Social life did not satisfy him; the ambitious Bismarck missed big politics.

However, only one week in the company of Katerina Orlova-Trubetskoy was enough for Bismarck to be captured by the charms of this young attractive 22-year-old woman.

In January 1861, King Frederick William IV died and was replaced by former regent William I, after which Bismarck was transferred as ambassador to Paris.

The affair with Princess Ekaterina Orlova continued after his departure from Russia, when Orlova’s wife was appointed Russian envoy to Belgium. But in 1862, at the resort of Biarritz, a turning point occurred in their whirlwind romance. Katerina’s husband, Prince Orlov, was seriously wounded in the Crimean War and did not take part in his wife’s fun festivities and bathing. But Bismarck accepted. She and Katerina almost drowned. They were rescued by the lighthouse keeper. On this day, Bismarck would write to his wife: “After several hours of rest and writing letters to Paris and Berlin, I took a second sip of salt water, this time in the harbor when there were no waves. A lot of swimming and diving, dipping into the surf twice would be too much for one day.” Bismarck accepted I took this as a sign from above and did not cheat on my wife again. Moreover, King William I appointed him Prime Minister of Prussia, and Bismarck devoted himself entirely to “big politics” and the creation of a unified German state.

Bismarck continued to use Russian throughout his political career. Russian words regularly slip into his letters. Having already become the head of the Prussian government, he even sometimes made resolutions on official documents in Russian: “Impossible” or “Caution.” But the Russian “nothing” became the favorite word of the “Iron Chancellor”. He admired its nuance and polysemy and often used it in private correspondence, for example: “Alles nothing.”

One incident helped him penetrate into the secret of the Russian “nothing”. Bismarck hired a coachman, but doubted that his horses could go fast enough. "Nothing!" - answered the driver and rushed along the uneven road so briskly that Bismarck became worried: “You won’t throw me out?” "Nothing!" - answered the coachman. The sleigh overturned, and Bismarck flew into the snow, bleeding his face. In a rage, he swung a steel cane at the driver, and he grabbed a handful of snow with his hands to wipe Bismarck’s bloody face, and kept saying: “Nothing... nothing!” Subsequently, Bismarck ordered a ring from this cane with the inscription in Latin letters: “Nothing!” And he admitted that in difficult moments he felt relief, telling himself in Russian: “Nothing!” When the “Iron Chancellor” was reproached for being too soft towards Russia, he replied:

In Germany, I’m the only one who says “nothing!”, but in Russia – the whole people!

Bismarck always spoke with admiration about the beauty of the Russian language and knowledgeably about its difficult grammar. “It is easier to defeat ten French armies,” he said, “than to understand the difference between perfect and imperfect verbs.” And he was probably right.

The “Iron Chancellor” was firmly convinced that a war with Russia could be extremely dangerous for Germany. The existence of a secret treaty with Russia in 1887—the “reinsurance treaty”—shows that Bismarck was not above acting behind the backs of his own allies, Italy and Austria, in order to maintain the status quo in both the Balkans and the Middle East.

Rivalry between Austria and Russia in the Balkans meant that Russia needed support from Germany. Russia needed to avoid aggravating the international situation and was forced to lose some of the benefits of its victory in the Russian-Turkish war. Bismarck presided over the Berlin Congress devoted to this issue. The Congress turned out to be surprisingly effective, although Bismarck had to constantly maneuver between representatives of all the great powers. On July 13, 1878, Bismarck signed the Treaty of Berlin with representatives of the great powers, which established new borders in Europe. Then many of the territories transferred to Russia were returned to Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina were transferred to Austria, and the Turkish Sultan, filled with gratitude, gave Cyprus to Britain.

After this, a sharp pan-Slavist campaign against Germany began in the Russian press. The coalition nightmare arose again. On the verge of panic, Bismarck invited Austria to conclude a customs agreement, and when she refused, even a mutual non-aggression treaty. Emperor Wilhelm I was frightened by the end of the previous pro-Russian orientation of German foreign policy and warned Bismarck that things were moving toward an alliance between Tsarist Russia and France, which had become a republic again. At the same time, he pointed out the unreliability of Austria as an ally, which could not deal with its internal problems, as well as the uncertainty of Britain’s position.

Bismarck tried to justify his line by pointing out that his initiatives were taken in the interests of Russia. On October 7, 1879, he concluded a “Mutual Treaty” with Austria, which pushed Russia into an alliance with France. This was Bismarck's fatal mistake, destroying the close relations between Russia and Germany. A tough tariff struggle began between Russia and Germany. From that time on, the General Staffs of both countries began to develop plans for a preventive war against each other.

P.S. Bismarck's legacy.

Bismarck bequeathed to his descendants never to directly fight with Russia, since he knew Russia very well. The only way to weaken Russia according to Chancellor Bismarck is to drive a wedge between a single people, and then pit one half of the people against the other. For this it was necessary to carry out Ukrainization.

And so Bismarck’s ideas about the dismemberment of the Russian people, thanks to the efforts of our enemies, came true. Ukraine has been separated from Russia for 23 years. The time has come for Russia to return Russian lands. Ukraine will only have Galicia, which Russia lost in the 14th century and it has already been under anyone, and since then has never been free.That’s why Bendera’s people are so angry with the whole world. It's in their blood.

To successfully implement Bismarck's ideas, the Ukrainian people were invented. And in modern Ukraine, a legend about a certain mysterious people is being circulated - ukrah, who supposedly flew from Venus and are therefore an exceptional people. TO of course, none ukrov and Ukrainians in ancient times It never happened. Not a single excavation confirms this.

It is our enemies who are implementing the idea of the iron chancellor Bismarck to dismember Russia. Since the beginning of this process, the Russian people have already endured six different waves Ukrainization:

- from the end of the 19th century until the Revolution - in the occupied Austrians of Galicia;

- after the Revolution of 17 - during the “banana” regimes;

- in the 20s - the bloodiest wave of Ukrainization, carried out by Lazar Kaganovich and others. (In the Ukrainian SSR in the 1920s - 1930s, the widespread introduction of the Ukrainian language and culture. Ukrainization in those years can be considered as an integral element of the all-Union campaign indigenization.)

- during the Nazi occupation of 1941-1943;

- during the time of Khrushchev;

- after the rejection of Ukraine in 1991 - permanent Ukrainization, especially aggravated after the usurpation of power by Orangeade. The process of Ukrainization is generously financed and supported by the West and the United States.

Term Ukrainization is now used in relation to state policy in independent Ukraine (after 1991), aimed at the development of the Ukrainian language, culture and its implementation in all areas at the expense of the Russian language.

It should not be understood that Ukrainization was carried out periodically. No. Since the beginning of the 20s, it has been and is ongoing continuously; the list reflects only its key points.

200 years ago, on April 1, 1815, the first Chancellor of the German Empire, Otto von Bismarck, was born. This German statesman went down as the creator of the German Empire, the “Iron Chancellor” and the de facto leader of the foreign policy of one of the greatest European powers. Bismarck's policies made Germany the leading military-economic power in Western Europe.

Youth

Otto von Bismarck (Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen) was born on April 1, 1815 at Schönhausen Castle in the Brandenburg Province. Bismarck was the fourth child and second son of a retired captain of a small nobleman (they were called Junkers in Prussia) Ferdinand von Bismarck and his wife Wilhelmina, née Mencken. The Bismarck family belonged to the ancient nobility, descended from the knights who conquered the Slavic lands on Labe-Elbe. The Bismarcks traced their ancestry back to the reign of Charlemagne. The Schönhausen estate has been in the hands of the Bismarck family since 1562. True, the Bismarck family could not boast of great wealth and was not one of the largest landowners. The Bismarcks have long served the rulers of Brandenburg in peaceful and military fields.

From his father, Bismarck inherited toughness, determination and willpower. The Bismarck family was one of the three most self-confident families of Brandenburg (Schulenburg, Alvensleben and Bismarck), whom Frederick William I called “bad, disobedient people” in his “Political Testament”. My mother came from a family of government employees and belonged to the middle class. During this period in Germany there was a process of merging of the old aristocracy and the new middle class. From Wilhelmina, Bismarck received the liveliness of the mind of an educated bourgeois, a subtle and sensitive soul. This made Otto von Bismarck a very extraordinary person.

Otto von Bismarck spent his childhood on the family estate of Kniephof near Naugard, in Pomerania. Therefore, Bismarck loved nature and retained a sense of connection with it throughout his life. He received his education at the Plamann private school, the Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium and the Zum Grauen Kloster Gymnasium in Berlin. Bismarck graduated from his last school at the age of 17 in 1832, having passed the matriculation exam. During this period, Otto was most interested in history. In addition, he was fond of reading foreign literature and learned French well.

Otto then entered the University of Göttingen, where he studied law. Study attracted little attention from Otto at that time. He was a strong and energetic man, and gained fame as a reveler and fighter. Otto took part in duels, various pranks, visited pubs, chased women and played cards for money. In 1833, Otto moved to the New Metropolitan University in Berlin. During this period, Bismarck was mainly interested, apart from “pranks,” in international politics, and his area of interest went beyond the borders of Prussia and the German Confederation, within the framework of which the thinking of the overwhelming majority of young nobles and students of that time was limited. At the same time, Bismarck had high self-esteem; he saw himself as a great man. In 1834 he wrote to a friend: “I will become either the greatest scoundrel or the greatest reformer of Prussia.”

However, Bismarck's good abilities allowed him to successfully complete his studies. Before exams, he visited tutors. In 1835 he received a diploma and began working in the Berlin Municipal Court. In 1837-1838 served as an official in Aachen and Potsdam. However, he quickly became bored with being an official. Bismarck decided to leave public service, which went against the will of his parents, and was a consequence of his desire for complete independence. Bismarck was generally distinguished by his craving for complete freedom. The career of an official did not suit him. Otto said: “My pride requires me to command, and not to carry out other people’s orders.”

Bismarck, 1836

Bismarck the landowner

Since 1839, Bismarck has been developing his Kniephof estate. During this period, Bismarck, like his father, decided to “live and die in the countryside.” Bismarck studied accounting and agriculture on his own. He proved himself to be a skillful and practical landowner who knew well both the theory of agriculture and practice. The value of Pomeranian estates increased by more than a third during the nine years that Bismarck ruled them. At the same time, three years fell during the agricultural crisis.

However, Bismarck could not be a simple, albeit intelligent, landowner. There was a power hidden within him that did not allow him to live peacefully in the countryside. He still gambled, sometimes in an evening he lost everything that he had managed to accumulate over months of painstaking work. He campaigned with bad people, drank, and seduced the daughters of peasants. He was nicknamed “mad Bismarck” for his violent temper.

At the same time, Bismarck continued his self-education, read the works of Hegel, Kant, Spinoza, David Friedrich Strauss and Feuerbach, and studied English literature. Byron and Shakespeare fascinated Bismarck more than Goethe. Otto was very interested in English politics. Intellectually, Bismarck was an order of magnitude superior to all the Junker landowners around him. In addition, Bismarck, a landowner, participated in local government, was a deputy from the district, deputy landrat and a member of the Landtag of the province of Pomerania. He expanded the horizons of his knowledge through travel to England, France, Italy and Switzerland.

In 1843, a decisive turn took place in Bismarck's life. Bismarck made acquaintance with Pomeranian Lutherans and met the fiancée of his friend Moritz von Blankenburg, Maria von Thadden. The girl was seriously ill and dying. The personality of this girl, her Christian beliefs and fortitude during her illness struck Otto to the depths of his soul. He became a believer. This made him a staunch supporter of the king and Prussia. Serving the king meant serving God for him.

In addition, there was a radical turn in his personal life. At Maria's, Bismarck met Johanna von Puttkamer and asked for her hand in marriage. Marriage to Johanna soon became Bismarck's main support in life, until her death in 1894. The wedding took place in 1847. Johanna gave birth to Otto two sons and a daughter: Herbert, Wilhelm and Maria. A selfless wife and caring mother contributed to Bismarck's political career.

Bismarck and his wife

"Raging Deputy"

During the same period, Bismarck entered politics. In 1847 he was appointed representative of the Ostälb knighthood in the United Landtag. This event was the beginning of Otto's political career. His activities in the interregional body of class representation, which mainly controlled the financing of the construction of the Ostbahn (Berlin-Königsberg road), mainly consisted of delivering critical speeches directed against the liberals who were trying to form a real parliament. Among conservatives, Bismarck enjoyed a reputation as an active defender of their interests, who was able, without delving too deeply into substantive argumentation, to create “fireworks”, distract attention from the subject of the dispute and excite minds.

Opposing the liberals, Otto von Bismarck helped organize various political movements and newspapers, including the New Prussian Newspaper. Otto became a member of the lower house of the Prussian parliament in 1849 and the Erfurt parliament in 1850. Bismarck was then an opponent of the nationalist aspirations of the German bourgeoisie. Otto von Bismarck saw in the revolution only the “greed of the have-nots.” Bismarck considered his main task to be the need to point out the historical role of Prussia and the nobility as the main driving force of the monarchy, and the defense of the existing socio-political order. The political and social consequences of the 1848 revolution, which engulfed large parts of Western Europe, had a profound impact on Bismarck and strengthened his monarchical views. In March 1848, Bismarck even planned to march with his peasants on Berlin to end the revolution. Bismarck occupied ultra-right positions, being more radical even than the monarch.

During this revolutionary time, Bismarck acted as an ardent defender of the monarchy, Prussia and the Prussian Junkers. In 1850, Bismarck opposed a federation of German states (with or without the Austrian Empire), as he believed that this unification would only strengthen the revolutionary forces. After this, King Frederick William IV, on the recommendation of King Adjutant General Leopold von Gerlach (he was the leader of an ultra-right group surrounded by the monarch), appointed Bismarck as Prussia's envoy to the German Confederation, in the Bundestag meeting in Frankfurt. At the same time, Bismarck also remained a deputy of the Prussian Landtag. The Prussian conservative debated so fiercely with the liberals over the constitution that he even fought a duel with one of their leaders, Georg von Vincke.

Thus, at the age of 36, Bismarck took the most important diplomatic post that the Prussian king could offer. After a short stay in Frankfurt, Bismarck realized that further unification of Austria and Prussia within the framework of the German Confederation was no longer possible. The strategy of the Austrian Chancellor Metternich, trying to turn Prussia into a junior partner of the Habsburg Empire within the framework of “Middle Europe” led by Vienna, failed. The confrontation between Prussia and Austria in Germany during the revolution became obvious. At the same time, Bismarck began to come to the conclusion that war with the Austrian Empire was inevitable. Only war can decide the future of Germany.

During the Eastern Crisis, even before the start of the Crimean War, Bismarck, in a letter to Prime Minister Manteuffel, expressed concern that the policy of Prussia, which fluctuates between England and Russia, if deviated towards Austria, an ally of England, could lead to war with Russia. “I would be careful,” noted Otto von Bismarck, “to moor our elegant and durable frigate to an old, worm-eaten warship of Austria in search of protection from a storm.” He proposed to wisely use this crisis in the interests of Prussia, and not England and Austria.

After the end of the Eastern (Crimean) War, Bismarck noted the collapse of the alliance of the three eastern powers - Austria, Prussia and Russia, based on the principles of conservatism. Bismarck saw that the gap between Russia and Austria would last a long time and that Russia would seek an alliance with France. Prussia, in his opinion, had to avoid possible alliances opposing each other, and not allow Austria or England to involve it in an anti-Russian alliance. Bismarck increasingly took anti-British positions, expressing his distrust in the possibility of a productive union with England. Otto von Bismarck noted: “The security of England’s island location makes it easier for her to abandon her continental ally and allows her to abandon him to the mercy of fate, depending on the interests of English politics.” Austria, if it becomes an ally of Prussia, will try to solve its problems at the expense of Berlin. In addition, Germany remained an area of confrontation between Austria and Prussia. As Bismarck wrote: “According to the policy of Vienna, Germany is too small for the two of us... we both cultivate the same arable land...”. Bismarck confirmed his earlier conclusion that Prussia would have to fight against Austria.

As Bismarck improved his knowledge of diplomacy and the art of statecraft, he increasingly moved away from the ultra-conservatives. In 1855 and 1857 Bismarck made “reconnaissance” visits to the French Emperor Napoleon III and came to the conclusion that he was a less significant and dangerous politician than Prussian conservatives believed. Bismarck broke with Gerlach's entourage. As the future “Iron Chancellor” said: “We must operate with realities, not fictions.” Bismarck believed that Prussia needed a temporary alliance with France to neutralize Austria. According to Otto, Napoleon III de facto suppressed the revolution in France and became the legitimate ruler. Threatening other states with the help of revolution is now “England’s favorite pastime.”

As a result, Bismarck began to be accused of betraying the principles of conservatism and Bonapartism. Bismarck answered his enemies that “... my ideal politician is impartiality, independence in decision-making from sympathy or antipathy towards foreign states and their rulers.” Bismarck saw that stability in Europe was more threatened by England, with its parliamentarism and democratization, than by Bonapartism in France.

Political "study"

In 1858, the brother of King Frederick William IV, who suffered from a mental disorder, Prince Wilhelm, became regent. As a result, Berlin's political course changed. The period of reaction was over and Wilhelm proclaimed a "New Era", ostentatiously appointing a liberal government. Bismarck's ability to influence Prussian policy fell sharply. Bismarck was recalled from the Frankfurt post and, as he himself bitterly noted, sent “to the cold on the Neva.” Otto von Bismarck became envoy to St. Petersburg.

The St. Petersburg experience greatly helped Bismarck as the future Chancellor of Germany. Bismarck became close to the Russian Foreign Minister, Prince Gorchakov. Gorchakov would later assist Bismarck in isolating first Austria and then France, which would make Germany the leading power in Western Europe. In St. Petersburg, Bismarck will understand that Russia still occupies key positions in Europe, despite the defeat in the Eastern War. Bismarck studied well the alignment of political forces around the tsar and in the capital's "society", and realized that the situation in Europe gives Prussia an excellent chance, which comes very rarely. Prussia could unite Germany, becoming its political and military core.

Bismarck's activities in St. Petersburg were interrupted due to a serious illness. Bismarck was treated in Germany for about a year. He finally broke with the extreme conservatives. In 1861 and 1862 Bismarck was twice presented to Wilhelm as a candidate for the post of Foreign Minister. Bismarck outlined his view on the possibility of uniting a “non-Austrian Germany.” However, Wilhelm did not dare to appoint Bismarck as minister, since he made a demonic impression on him. As Bismarck himself wrote: “He considered me more fanatical than I really was.”

But at the insistence of War Minister von Roon, who patronized Bismarck, the king nevertheless decided to send Bismarck “to study” in Paris and London. In 1862, Bismarck was sent as envoy to Paris, but did not stay there long.

To be continued…