Huss Jan (Huss, John) (c. 1372-1415), Czech. religious reformer. As a preacher in Prague and a zealous supporter of Wycliffe's views, he aroused the hostility of the church and was excommunicated (1411), put on trial and burned at the stake. After his death he was declared a martyr, his followers ("Hussites") began a war against the "Holy Roman Empire", and at first inflicted several. serious defeats for the emperor's army.

Excellent definition

Incomplete definition ↓

Jan Hus

The great Czech religious figure Jan Hus was born around 1369 in the town of Husinec, on the border of Bohemia and Bavaria. His parents were apparently poor peasants. Gus lost his father early, and his mother raised him. Having graduated from the Prachatice school located not far from Husinets, Hus went to study in the capital around 1390, where he enrolled as a student at the Faculty of Liberal Arts of the University of Prague. In 1393 he received a bachelor's degree in liberal arts, and in 1396 a master's degree. Soon after this, around 1401, he was ordained priest and in the same year he was elected dean of the Faculty of Arts. Finally, in October 1402, Hus was elected for the first time to the highest academic position of rector of the university. Around the same time, a significant change occurred in Hus's lifestyle. Under the influence of books - primarily the writings of Wycliffe - he turned from a cheerful secular man almost into an ascetic. Much evidence has been preserved of the deep influence of the ideas of the English reformer on Hus. One of Hus’s acquaintances later recalled that he once admitted: “Wycliffe’s books opened my eyes, and I read them and re-read them.” However, this influence should not be exaggerated. Although Hus's own writings are in places literal extracts from Wycliffe, he did not accept his teaching in its entirety. In particular, on the important issue of the Eucharist, he had his own opinion. If Wycliffe taught that during transubstantiation, bread remains bread and Christ is present in the sacrament only symbolically, and not physically, then Huss (in full agreement with Catholic teaching) believed that Christ is actually contained in the holy sacrament approximately in the same way as the soul is contained in a person - the appearance of the bread covers Him as the body covers the soul. Hus did not share many of Wycliffe's other radical views. He did not completely deny papal authority, deeply respected the sacrament of the priesthood, and accepted the general view of the Catholic Church on the important mediating role of the clergy in the relationship between God and the laity. Their views on the meaning of Scripture also differed. If for Wycliffe Scripture contained the entire Christian teaching, then for Hus it was only its basis. Like all Catholics, he believed that teaching continued to develop through the rules of holy popes and the decrees of councils. Without touching on Catholic dogmas, Hus, however, very severely castigated the vices of the modern church. His speeches met with a lively response from the laity and had a huge impact on his contemporaries. During the time of Hus, Czech society experienced a rise in national consciousness, accompanied by opposition to the Catholic clergy. Prague citizens loudly demanded that sermons in churches be delivered not only in Latin and German, but also in Czech. King Wenceslas IV supported this demand, and soon a new chapel was opened in Prague, called Bethlehem Chapel. Several very eloquent preachers have spoken here, but none of them acquired a fraction of the importance that Hus's speeches gave to this chapel. His pale, emaciated face, his thoughtful eyes struck the parishioners even before his voice was heard. Against the background of the general decline in the morality of the clergy, his reputation has always been crystal clear. One of Hus’s personal enemies later wrote about him: “His life was harsh, his behavior was impeccable, his selflessness was such that he never took anything for his needs and did not accept any gifts or offerings.” In his sermons, he did not strive to amaze parishioners with the beauty of his style; Hus’s speech was neither ardent nor brilliant, so the listeners were affected mainly by the strength and sincerity of his conviction. Hus' denunciations were always harsh and merciless; he spared neither secular nor clergy, he constantly spoke about the arrogance of the clergy, about the pursuit of hierarchical promotions, about self-interest and greed. There were more than enough reasons for this. The state of the church at that time presented a most bleak sight. It generally seemed to many believers that it had turned from “God’s house” into an institution intended solely for collecting money. The popes imposed an annual tax on the entire Christian world and took more than what was established. The papal court openly traded ecclesiastical positions. The Roman Curia generated large incomes from the sale of indulgences, which outraged all respectable Christians to the depths of their souls. To all this was added many years of dual papacy. In 1378, Urban VI and Clement VII were simultaneously elected to the papal throne. After this, for half a century, Europe saw “the abomination of desolation in the holy place.” Some states recognized the Roman high priest. Others preferred his opponent, who established his court in Avignon. Popes and antipopes continually cursed each other and quarreled obscenely. There was no end in sight to the schism, and respectable Christians began to doubt that Christ was watching over his church. It was clear to everyone that both high priests were false vicars of Christ, both antichrists, and that the only way to improve matters was to overthrow and depose both. The Czech Church also presented a sad picture of decline. Many Prague priests lived almost openly with their mistresses, held feasts with dancing, played dice, hunted and committed other inappropriate acts. The monks (there were more than a thousand of them in Prague alone) spent most of their time in idleness and indulged in a wide variety of vices. Many of them were noticed in relationships with women. But worst of all was the unbridled thirst for gold that then gripped the entire church. “The last penny that the old woman will tie in her bedspread to protect it from a thief or robber, the priest and monk will be able to lure this penny from her...” said Huss. “Wealth has poisoned and spoiled the church. Where do wars, excommunications, quarrels between popes and bishops come from? Dogs squabble over bones. Take away the bone and the world will be restored. Where does bribery, simony come from, where does the impudence of clergy come from, where does adultery come from? Everything comes from this poison.” Hus's harsh speeches greatly offended the clergy. Numerous complaints began to be received against Prague Archbishop Zbynek. “Against us,” wrote one of the informers, “outrageous sermons are heard that torment the souls of devout people, destroy faith and make the clergy hateful to the people.” Many were extremely irritated by Hus's assertion that a priest who demands money for performing the sacraments, especially from the poor, is guilty of “simony and heresy.” They were also indignant because Hus said about the death of one canon: “I would not like to die with such income.” Angry at Hus, his enemies for a long time did not have the opportunity to accuse him of anything serious. But then more and more often (and completely unfoundedly) heretical errors began to be attributed to him. In 1403, a controversy broke out at the University of Prague over the theological teachings of Wycliffe. The German master Hübner extracted 45 heretical provisions from his treatises, for the discussion of which rector Gerraser convened all Prague doctors and masters. The meeting was stormy. When the public notary read the reprehensible paragraphs, a whole phalanx of Czech masters, who saw Wycliffe as their teacher, stood up for the new ideas. But they could not achieve victory, and at the end of the debate the majority decided: “That no one should teach, preach or affirm, either publicly or secretly, the above-mentioned paragraphs under pain of violating the oath.” This ruling was initially not followed by any punitive measures. Among Hus's courtiers and colleagues there were many Wycliffists, and he himself never hid his affection for the English teacher in his sermons. But over the years, the hostility of the official church to Wycliffe's ideas became more and more irreconcilable. At the end of 1407, Pope Gregory XII sent a bull to the Archbishop of Prague demanding the eradication of sectarians preaching against the doctrine of Holy Communion. After this, in 1408, a new, more severe persecution began. Again the notorious 45 paragraphs were condemned, Wycliffe's ideas were strictly forbidden to be taught and defended. The Wycliffe party in the Czech Republic was defeated and was soon to disappear completely, but then, fortunately for it, serious friction arose between the king and the archbishop. The reason for them was a church schism: while Archbishop Zbynek and his entire chapter continued to focus on Rome, King Wenceslas (who advocated the overthrow of both rivals - both the Roman Gregory XII and the Avignon Benedict XIII) demanded neutrality from his subjects. (It was assumed that at the Council of Pisa, the convening of which Wenceslas actively supported, a legitimate pope would finally be elected, who would put an end to the long-standing schism.) The debate over neutrality had important consequences for the University of Prague. From its very foundation it was not a purely Czech national institution, since it served as the main intellectual center not only for the Czechs, but also for the Germans. According to the charter, the university staff - both professors and students - was divided into four nations - Czech, Polish, Bavarian and Saxon. In all matters of internal self-government each nation had one vote. Formally, this proclaimed the equality of nations, but in fact such an organization ensured the complete dominance of the German party, for the Bavarians and Saxons were natural Germans, and mainly immigrants from Silesia were enrolled in the Polish nation. The question of neutrality, raised by the king, caused a split in the university along national lines. German professors and the highest Czech clergy stood firmly behind Gregory, and the Czech party, led by Hus, unanimously spoke out for neutrality. The angry archbishop called Hus a “disobedient son of the church” and forbade him to perform any priestly duties. Along with him, the rest of the supporters of neutrality were rejected. But this measure, instead of frightening the Czech nation, inspired it. The sympathies of the Prague population were entirely on their side. Hus suggested turning to the king with a request to change the university charter in such a way that when deciding all issues, the votes of Germans and Czechs would be equal. The king at first received Hus very unfriendly, but then granted his wish. The result of all these movements was the split of the University of Prague. The Germans, outraged by the innovation, began to demand the restoration of their rights. Vaclav flared up and ordered the rector to be driven away and his seal and keys to be taken away. Then, on May 16, 1409, more than five thousand Germans - professors and students - left Prague and retired to Leipzig, where they founded a new German university. As a result, Wycliffe's Czech followers grew stronger again. The victory over the Germans made the name Hus extremely popular in the Czech Republic, and especially in Prague. In October 1409, elections were held for the first rector of the university after the schism. It was Jan Hus for the second time. The council of prelates in Pisa, which met at the same time with the support of Wenceslas, elected (in defiance of Gregory and Benedict) Alexander V as the new pope. The archbishop, after a futile struggle with the king, was forced to acknowledge this choice. But he continued to be Hus's enemy. In March 1410, Zbynek obtained from the pope a bull condemning Wycliffe's heresy and giving him the broadest powers to eradicate it. Four months later, he ordered all the books of Wycliffe that he managed to get his hands to be publicly burned, and then pronounced a curse on Hus and his supporters. But when the priests began, in accordance with his orders, to proclaim the excommunication of Huss, the people forcibly opposed this in all the churches. Most of the Prague priests were so intimidated that they no longer dared repeat the curse. But in some places the archbishop’s supporters prevailed. For almost a month, unrest and confusion continued in the Prague churches. Finally, the king stopped them with strict measures. In general, victory in the Czech Republic went to the followers of Hus. The university and the royal court were entirely on his side, and the people of Prague warmly supported him. But outside the kingdom, the attitude towards him remained exactly the opposite - under the influence of papal bulls, the opinion that Hus was a real heretic gradually established itself here. They began to demand him to go to Rome for trial, but Hus did not go because he feared reprisals. Then in February 1411 he was given over to the papal curse. However, Hus, not paying attention to either the archbishop's or the papal excommunications, continued to preach in his chapel. In the last years of his life, like Wycliffe, he devoted much effort to translating the Bible into Czech. By this time, there were already Czech translations of many books of the Holy Scriptures, but not all of them were of satisfactory quality, differing in style and language (a single literary Czech language did not yet exist at that time; there were several dialects). Hus carefully reviewed all these translations, correcting errors and flaws, and, like Wycliffe, finally created a Bible for the people, which they could read without difficulty. Meanwhile, the persecution of Hus intensified. In 1412, Pope John XXIII ordered him to be excommunicated again. The curse had to be repeated with the ringing of bells, with the lighting and extinguishing of candles. The formula of the curse said that from now on no one should give Hus any food, drink, or shelter, and the place on which he stands is subject to interdict. All faithful sons of the church were charged with the duty of detaining Hus wherever they met him, and delivering him into the hands of the archbishop or bishop. The Pope ordered the Bethlehem Chapel to be destroyed as a hotbed of heresy. There was no way to carry out these threats in Prague, where Hus had many supporters. When one day the enemies of Hus tried to disrupt a service in the Bethlehem chapel, crowds of people instantly came running, and the terrified opponents left with nothing. The king also remained the patron of Hus, although he really did not like the latter’s quarrel with the pope - it cast a shadow on Wenceslas’s reputation, for his enemies spread rumors about him in Europe as a defender of heretics. At the end of 1412, he persuaded Hus to leave Prague and thereby put an end to the unrest. While outside the capital, he wrote his main work, “On the Church.” It became his testament for Czech reformers. In the fall of 1414, at the request of Emperor Sigismund, a church council met in Constance, which was supposed to put an end to the protracted schism of the Western Church. (The Council of Pisa failed to do this; in fact, it even strengthened it, since instead of two popes there were three). Along the way, other complicated church matters were resolved in Constance. The case of Huss was one of them, and the emperor sent him a personal invitation to the council. Sigismund wrote that he would give Hus the opportunity to express his views, and promised to release him to his homeland even if Hus did not obey the decision of the council. Many of Hus's friends, knowing Sigismund's fickleness, dissuaded him from this trip. However, Gus decided to go. It seemed to him that by appearing at the council, he would justify himself before his accusers and convince not only the laity, but also the prelates of the truth of his ideas. When Hus arrived in Constance, it was already noisy and crowded, although the cathedral had not yet opened. At first, no one paid attention to him and it seemed that no one cared about him. But it was only an illusion. His enemies hated him too much to let him escape from their hands. The reprisal against the Czech reformer was a foregone conclusion. Hus expected a fair trial or public debate and was confident of his success. However, his fate was decided in a completely different way. On November 28, 1414, the cardinals, having gathered before Pope John XXIII, privately discussed the teachings of Hus and decided that he should be taken into custody. On the same day, the unfortunate man was imprisoned in a Dominican monastery, in a gloomy, damp cell adjacent to the cloaca. This happened without the knowledge of the emperor. At first, Sigismund became very angry and announced his intention to release the prisoner by force. But after some time, he sharply lowered his tone and gave the clergy complete power over the fate of his client. Hus was transferred to Gottlieben Castle, which belonged to the Bishop of Constance, chained and kept in great severity. In June 1415, the public trial of Hus began. There were three meetings in total, but at none of them Gus was allowed to speak freely. In order to give a legal appearance to the impending reprisal, they tried to attribute to him the spread of Wycliffe’s heretical provisions. Hus skillfully defended himself, although he was in a very difficult position - he had to single-handedly confront an entire council of hostile bishops. Formally, his guilt was never proven. The majority of the council members were ready to be satisfied with the life sentence of the accused. But this required that Hus admit his mistakes. He flatly refused. The prelates had no choice but to declare him a stubborn heretic and sentence him to be burned at the stake. The execution took place on July 6, 1415.

Jan Hus is the most famous Czech in world history. He was born in 1369 (according to other sources in 1371) in the village of Gusinets in South Bohemia into a peasant family.

In 1393 he graduated from the University of Prague, initially became a bachelor of theology, and then received a master's degree in liberal arts. He served as dean of the Faculty of Liberal Arts, and in 1402-1403. and 1409-1410 served as rector.

At the same time, in 1402, Hus was appointed rector and preacher of the Bethlehem Chapel in the old part of Prague, where he was mainly engaged in reading sermons in Czech.

In his sermons, he spoke out against church wealth, called for depriving the Church of property, subordinating it to secular power, condemned the corruption of the clergy and exposed the morals of the clergy, demanded reform of the Church, condemned simony, and spoke out against German dominance in the Czech Republic, in particular at the University of Prague. This criticism appealed to the nobility, who dreamed of seizing church lands and wealth, and even to King Wenceslas IV. The sermons of Jan Hus also met the demands of the burghers, who strived for a “cheap” Church.

In a conflict with the German magistrates of the University of Prague, who opposed the ideas of Jan Hus, King Wenceslas IV took his side and in 1409 signed the Decree of Kutnagorsk, which turned the University of Prague into a Czech educational institution; The management of the university passed into the hands of the Czechs, and the German masters left it. But at the same time, the University of Prague turned from an international center into a provincial educational institution.

1409-1412 is the time of Jan Hus’s complete break with the Catholic Church and the further development of his reformist teachings. Hus placed the authority of the Holy Scriptures above the authority of the pope, church councils and papal decrees, which, in his opinion, contradicted the Bible. Jan Hus's ideal was the early Christian church. Jan Hus recognized only the Holy Scripture as the source of faith. By 1410-1412, Jan Hus's position in Prague had worsened, and the Prague archbishop spoke out against him.

In 1412, Jan Hus opposed the sale of papal indulgences, which caused a conflict with Wenceslaus IV, who refused to further support the dangerous heretic, so this dealt a blow to his already weak international prestige. In 1413, a bull appeared with the excommunication of Jan Hus from the Church and an interdict (prohibition to perform church rites) on Prague and other Czech cities that would provide him with refuge. Under the pressure of circumstances, Jan Hus was forced to leave Prague and for 2 years lived in the castles of the nobles who patronized him, continuing his preaching work in Southern and Western Bohemia.

In exile, Jan Hus wrote his main work - a large essay “On the Church”, in which he criticized the entire organization of the Catholic Church and church orders, denied the special position of the pope, the necessity of his power, argued that priests should be deprived of secular power and left them with as much property as possible. as much as is necessary for a comfortable existence.

The Church saw a dangerous heresy in the teachings of Jan Hus, and in 1414 he was summoned to the German city of Constance for a church council, which met to put an end to the schism in the Church and condemn heresies. Jan Hus, having received a safe conduct from Emperor Sigismund I, decided to go to Constance and defend his views. However, in violation of all obligations, he was imprisoned, where he spent 7 months.

Then Hus was asked to abandon his writings. On July 6, 1415, Jan Hus was brought to the cathedral and a sentence was read, according to which, if he did not renounce his views, he would be sent to the stake. Jan Hus said:

I will not renounce!

He was immediately deprived of his priesthood and executed. They say that when Jan Hus was already standing on the flaring fire, one old woman threw a bundle of brushwood into the fire. She sincerely believed that the burning of a person was pleasing to God and that the fire would cleanse his soul.

Oh, holy simplicity! - exclaimed Gus.

This phrase has become a catchphrase.

The ashes of Jan Hus were thrown into the waters of the Rhine.

The execution of Jan Hus shook Czech society and caused an explosion of indignation that resulted in the Hussite movement. Jan Hus was declared a Czech saint.

The most famous and beloved historical hero of the Czech Republic is Jan Hus - scientist, writer, priest. Jan Hus was a native of the town of Husinec (Southern Bohemia). He was born in 1371, into a peasant family. In the Czech Republic he became a national hero during his lifetime. To this day, centuries after his death, Jan Hus enjoys great respect. Among the people [...]

The most famous and beloved historical hero of the Czech Republic is Jan Hus- scientist, writer, priest.

Jan Hus was a native of the city Gusinec(South Bohemia). He was born in 1371, into a peasant family. In the Czech Republic he became a national hero during his lifetime. To this day, centuries after his death, Jan Hus enjoys great respect. People consider him a saint, although he was not canonized. The Pope has repeatedly expressed his respect for the personality of Jan Hus, but refused to canonize this man as a saint.

During his lifetime, Hus preached against the evil caused to the people by the church.

He graduated from the University of Prague, became a bachelor, master, dean of the Faculty of Liberal Arts, and subsequently - rector of the university. He was a scientist, wrote scientific works on linguistics. His research is still used in Czech grammar today. At the same time (in 1402) Hus served as a preacher and rector of the Prague Bethlehem Chapel. Thousands of townspeople gathered in the chapel to listen to the preaching of the denouncing priest. Hus mercilessly denounced the greed of the rich and the bribery of the church.

Jan Hus is considered by many to be a fiery revolutionary, but he did not carry out a revolution - neither in politics nor in religion. He sought one thing from the church - that it observe the Law of God and act in accordance with Christian teaching. Hus harshly criticized the institution of the church. He was criticized for the sale of indulgences, drunkenness and riotous behavior of priests. He described terrible incidents in the lives of clergy. Thus, one Prague kanovnik (high church rank) lost money and clothes in a tavern; returned home at night, practically naked. He woke up the whole street by knocking and screaming. This priest committed such sprees three times. What example could he set for his parishioners?

It was precisely this behavior of church ministers that Jan Hus criticized. He himself was by no means a saint; he especially sinned as a student. He later honestly admitted this.

There is a lot of controversy regarding the appearance of Jan Hus. In the 19th century, he was often depicted as Christ, although he called himself fat. Several surviving images prove that the reformer was quite plump, bald and did not wear a beard.

There is another misconception. It is believed that it was because of Hus that the Cathedral of Constance. This is wrong. The council was convened to discuss issues of faith, and it took several months. This information was hidden from the people for a long time. Only after the uprising in the Czech Republic did everything change. It became common knowledge that the Pope who sentenced Jan Hus to death was a former pirate. (Pope John XXIII fled the Czech Republic. His name was subsequently adopted by another Pope to purify him.)

The concept of “Hussite wars” is associated by many with the personality of Jan Hus. However, Hus was burned on July 6, 1415 in the city Constanta. The Hussite wars began only in 1419 (they lasted until 1434). Jan Zizka- the hero of the Hussite wars - did not know Jan Hus. Theoretically, of course, he could attend the sermons of the reformer priest in the Bethlehem Chapel, but this has not been proven. And all the stories in literary works about the friendship that existed between two national heroes are just creative fiction.

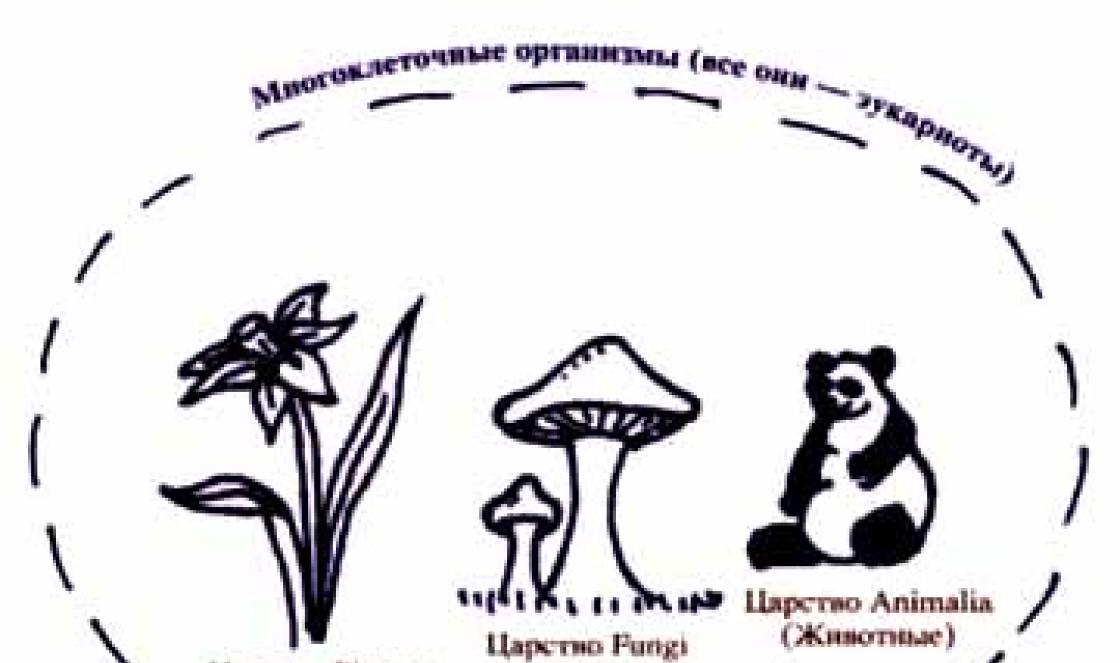

Hus did not want war and bloodshed. He just wanted the truth and wanted everyone to live righteously. In his scientific works and sermons, he often referred to the ideas of the Englishman John Wycliffe- professor and priest. (Wycliffe was highly revered in the Czech Republic.) The English professor sharply criticized the church, especially the idea of transubstantiation. This refers to the Christian rite of the Mass, during which the faithful are given a host (for the Orthodox - prosphora) and wine. It is believed that in the mouth of a believer these substances turn into the body and blood of Christ. John Wycliffe called this idea nonsense.

Hus also criticized the practice of communion. At that time, priests took communion with wine and bread; the laity were given only bread during mass. Hus tried to prove that during early Christianity everyone received communion in the same way. These were not just the details of church ritual - this approach equated ordinary parishioners with priests. (The followers of Jan Hus began to give communion to the laity with both bread and wine).

At one time, Wycliffe was also called to the Council. Hus was accused of following the ideas of the Englishman. After the conviction of Jan Hus, the churchmen decided to “deal with” Wycliffe. Since the English professor had been dead for a long time, his bones were dug out of the grave and ceremonially burned.

The Catholic Church still calls John Wycliffe a most dangerous heretic. Because of his ideas John Paul II and refused to canonize Jan Hus. In addition to his connections with Wycliffe, Hus is accused of criticizing the Catholic Church. It is believed that with his critical statements, Jan Hus changed the rank of clergyman.

The Czech people consider Jan Hus a saint and a national hero. He left a huge literary legacy and contributed to the Czech language, its spelling and orthography. This contributed to the spread of literacy among ordinary Czechs.

Hus's works were accessible and understandable to the people. He developed his own style of polemic, establishing a new type of prose in Czech literature.

How can I save up to 20% on hotels?

It’s very simple - look not only on booking. I prefer the search engine RoomGuru. He searches for discounts simultaneously on Booking and on 70 other booking sites.

The message about Jan Hus, the Czech religious reformer, the national hero of the Czech Republic, will tell you his short biography and some interesting facts from his life. The information in the report will help you prepare for classes.

Jan Huss short biography

The future reformer was born around 1370 in Southwestern Bohemia into a peasant family. Around 1390, Jan entered the University of Prague, from which he graduated in 1393 with a master's degree. Having decided to connect his life with spirituality, Hus was ordained a priest in 1400. And after 2 years, the activist received the position of preacher in the Bethlehem Chapel in Prague.

Jan Hus began studying the scholastic dispute between supporters of realism and nominalism. A fierce national and religious struggle began in the country. And these questions were of great interest to the young reformer. Simultaneously with his work as a preacher, Hus served as rector and dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Prague. From 1403, on the instructions of his student and Prague Archbishop Zbynek Zaichik, Jan Hus began to preach at councils and congresses in Prague before the clergy.

Why did Jan Hus criticize the Catholic Church?

The activities of Jan Hus were aimed at exposing the shortcomings of the clergy and condemning the luxury and wealth of the Church. Although he considered himself a son of the Catholic Church, he adhered to two Protestant theses - he believed that the Holy Scriptures were more authoritative than the decisions of councils and the pope and supported the teachings and views of St. Augustine. His sermons attracted a large number of listeners, but the clergy, especially the German ones, showed dissatisfaction with them.

Finally, in 1403, the German party decisively opposed Jan Hus. A debate took place at the University of Prague, at which a large number of clergy voted to prohibit him from preaching at church congresses, and then from serving as a priest. In 1409, the Council of Pisa was convened to deal with the issues of the Great Schism between the Czech and German clergy. In 1410, a new accusation was brought against the former priest. The verdict of the church council on Jan Hus was as follows: he was even banned from any teaching activity at the university and excommunicated from the church.

During this period, Pope John XXIII declared a crusade against King Ladislaus of Naples, who supported Antipope Gregory XII. Gregory XII issued a bull of indulgence to those who would side with him. Hus condemned indulgences and appealed to King Wenceslas, but received no support. In October 1412, he retired to Kozijrádek Castle to his friend, continuing to preach secretly. A treatise in Latin “On the Church” and other works in Czech were written in the castle.

The Catholic Church and King Vaclav of the Czech Republic did not like the growing popularity of Jan Hus and they constantly watched him and put a spoke in his wheels. Therefore, the activist had to hide. It is known that in 1412 the former priest lived in the vicinity of Prague, but no one knew where exactly. The two kings Wenceslas and Sigismund hatched a conspiracy against him - Hus was invited to the next church council in 1414. His friends discouraged him from attending this event, but the reformer still went to defend the truth of his beliefs. What sentence was passed on Jan Hus at this council? He was arrested and deprived of the opportunity to defend his work. In prison, the leader was ill, and the clergy constantly urged him to renounce his teachings. And King Sigismund issued a decree on the execution of the Czech hero, whose trial lasted many months.

The last court hearing on July 6, 1415 sentenced Jan Hus to death by burning alive at the stake. And even being tied to a pillar, in the middle of a kindling fire, the reformer did not lose faith and continued to say hymns and prayers in the name of God.

- During my student years I liked to visit baths.

- According to his lifetime image, Hus was bald, fat and beardless.

- In the Czech Republic, Jan Hus is a national hero.

- While studying at the University of Prague, he constantly lacked money for food. And in order to prolong the “pleasure” of food, Gus made a spoon out of bread and ate pea soup with it.

- When the reformer was engaged in preaching activities, he built houses for poor people and students.

Jan Hus (1369-1415) - national hero of the Czech Republic, preacher, priest, thinker, worked as rector of the University of Prague. He was burned at the stake along with all his labors; such an execution served as a prerequisite for the start of hostilities waged by the followers of Jan Hus; in history they were called the “Hussite Wars.”

Childhood

The Middle Ages period is still far from us, so that we can accurately find out exactly when Jan Hus was born. According to some sources, he was born in 1369, according to others - in 1371. This happened in the small town of Gusinec, located in the south of the Czech Republic. In those days, the concept of “surname,” which had disappeared with Ancient Rome, was just beginning to be revived. So Jan Hus got his last name from the name of the city in which he was born - Gusinets.

The peasant family where the boy was born was very poor. Biographers were able to establish that his father’s name was Mikhail and in the family, in addition to Jan, there were two more sons. Despite poverty, the parents really wanted to send their child to school, hoping that he would study and become a priest. At the end of the 14th century, for a poor boy from a humble family, school was the only way to break into the people. Jan Hus' parents perceived schooling as a path not to knowledge, but to a quiet future life, relative material well-being, and good nutrition.

The nearest educational institution was in the town of Prachatice, from Gusinets it took an hour to walk. And the boy went to this school, spending two hours every day on the road (there and back). Compared to his hometown, Prachatitsa seemed bright and large to the child; the main road to Prague, southern Germany and Austria passed through it. A cathedral was built in the city, which seemed huge to little Jan. And also in Prachatice, by that time various types of crafts had already received great development, which to this day glorify the Czech Republic, especially the production of wonderful glass and silver shiny products.

The main school subjects for Jan Hus were rhetoric, dialectics and grammar. In the senior classes, astronomy, arithmetic and natural sciences were added.

University

Despite material difficulties and poverty, the family made every effort to promote Ian further. At the age of 18, the guy graduated from school and, together with his mother, went to Prague to enter university. Today this educational institution is one of the oldest universities in Europe.

Mom decided to present gifts to the university authorities in the form of a live goose from the homestead and a large soft white roll. However, already on the very outskirts of Prague, the goose ran away, and my mother had to please the management of the educational institution with only one roll. Either the pastries turned out to be too tasty, or Ian had decent knowledge, the guy was still accepted into the university.

The educational institution had three faculties - medical, theological and liberal arts. Jan Hus entered the Faculty of Arts because studying at the other two was much more expensive, although later his whole life was connected with theology, or rather with its criticism.

Jan Hus's student years were spent in complete poverty. He ate only pea soup, because it was cheaper than all other food. He didn’t even have anything to buy dishes for. Each time he made himself a spoon from bread crumbs in the hope that it would last him a long time. But all the time he ate this bread spoon of his along with the stew, as he was incredibly hungry.

In 1393, Jan Hus received a bachelor's degree, and in 1396, a master of arts.

Teaching activities

During his studies at the university, Jan Hus showed a penchant for theology (the science that studies religion). Therefore, immediately after he received his master’s degree, Gus was offered to stay at the educational institution and take up teaching.

The young teacher thought freely. With his students, Hus began to study the works of the English theologian and Oxford University professor John Wycliffe, despite the fact that his works in the field of theology were considered heretical in 1382. However, Ian was not afraid of this; he not only presented Wycliffe’s theory to the students, but also developed it. Hus rejected the spiritual, unlimited power of the Pope, arguing that the true head of the Catholic Church was Jesus Christ. And Ian denounced the wealth of the church much more categorically than Wycliffe.

Despite the fact that Jan Hus was a freethinker, and Wycliffe’s works were publicly burned at the stake, in 1401 the young teacher was appointed dean of the Faculty of Philosophy, and in 1402 rector at the University of Prague.

Jan Hus was the first rector of this educational institution, who was a Czech by nationality; until 1402, only Germans were given such a position. Moreover, it was an amazing career for the son of poor peasants.

Preaching activities

His career growth was explained by the fact that Gus, in addition to his extensive education, had undeniable talents and was a very popular speaker at that time. Since 1401, Hus held sermons in the Church of St. Michael, which attracted many people. And the very next year, 1402, he was appointed preacher and rector in the private Bethlehem chapel, which was located in the old part of Prague. This chapel was founded in 1391 and differed from the others in that services were conducted not in Latin, but in Czech. Sometimes about three thousand people gathered at Hus’s sermon.

In his stories, Jan touched on everyday life, which was very unusual for that time. Despite the fact that he himself was a deeply religious person, he criticized the church and exposed the shortcomings of people in church service. His opinion was contrary to the official policy of the Catholic Church:

- Priests were not supposed to sell church positions and sacraments. Money could only be taken from the rich, and then in small quantities necessary to satisfy the first vital needs of the clergyman.

- Despite the fact that one wants a calm and prosperous life, every Christian should not be afraid to risk it in search of the truth.

- The successors of Christ must be poor, like the apostles. But they, on the contrary, only think about increasing their wealth.

- Blind submission to the church is unacceptable; it is necessary to think with your own head. Hus cited words from Holy Scripture to this thesis: “If a blind man leads a blind man, both will end up in a pit.”

- Only just people deserve to have property. If a rich man is unjust, then he is a thief.

- An authority that violates God's commandments cannot be recognized by him.

Others also observed the depraved and cynical life of spiritual ministers, but they were afraid of punishment and tried to remain silent. Silence was unusual for Hus; he began to fight. Jan perfectly understood how dangerous his decision was, because he knew how heretics were burned at the stake throughout Europe by the Inquisition.

To promote his teachings, Hus used not only cathedral sermons. On his instructions, the walls in the Bethlehem chapel were painted with paintings with edifying subjects. He is the author of several songs that have become popular among the people, and a reformer of Czech spelling. Thanks to his Latin work “Czech Orthography,” books became more accessible to ordinary people. He is responsible for the development of diacritics.

Among other things, Jan was also a passionate patriot of the Czech Republic. He owns the translation of the Bible into Czech, thereby depriving the priests of their exclusive right to make money from its interpretation. Hus was also an ardent opponent of German dominance in the Czech Republic. Although the Czech Republic received legal recognition of independence in 1212, there were still Germans in all key positions (rectors, burgomasters, military commanders). Jan Hus preached that “in the Kingdom of Bohemia, according to the law of nature, Czechs should be first in positions.”

Persecution and execution

Larger and larger crowds of people gathered at the sermons of Jan Hus, and the heads of church institutions became increasingly restless; in the person of this preacher they saw their terrible and dangerous enemy.

In 1408, Hus's friends were arrested and accused of heresy. And in 1409, the Pope of Rome issued a bull against John himself (a bull is the most important papal document with a lead seal). According to this bull, the Archbishop of Prague took punitive action against Hus: he was forbidden to preach, and all of Jan’s books were collected and burned.

But Hus's influence on ordinary people continued to grow, and then in 1411 the Archbishop of Prague called him a heretic.

In the fall of 1414, the Pope’s patience ran out. On his initiative, Hus was summoned to the Ecumenical Council in the city of Constance. The preacher was told that the highest church hierarchs wanted to listen to him personally and understand his train of thought.

At that time, the Czech Republic was legally subordinate to Emperor Sigismund, who was also present at the Ecumenical Council. By his order, Jan Hus was given a safe conduct, which guaranteed the preacher an unhindered return to Prague. However, it later turned out that Sigismund not only deceived Hus by issuing him an ordinary travel document, but also demanded the death penalty at the stake for Jan.

Hus was accused of heresy, and also of organizing the expulsion of the Germans from the University of Prague. He was arrested and imprisoned in a dark, damp basement of a Dominican monastery. They demanded that Hus renounce his heretical views and repent. But Jan wrote a statement to the council: “They want me to renounce. But then I will betray my conscience and disgrace the faith of Christ. If I renounce the truth, then how can I then look at the sky and into the eyes of my people? I will never do this."

He was sentenced to death, which was carried out on July 6, 1415. Hus was taken out of the city of Constanta to a meadow, where a sharp wooden stake like a pillar was stuck into the ground in the middle. The preacher was tied to him with ropes and chains, and armfuls of firewood, brushwood, and bundles of straw were laid out around him. He, already consumed by fire, was asked one last time: “Renounce!” Gus did not do this and burned alive. After burning, so that no remains of him remained on the ground, the ashes were thrown into the stream of the Rhine River.

The execution of Jan Hus led to his followers (the Hussites) taking hostilities against the Catholics. The Hussite Wars were devastating for Europe, lasting from 1419 to 1434, neither side achieved any significant results, and opponents were forced to compromise.

To this day, Jan Hus has not been rehabilitated by the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, in modern Czechia he enjoys great respect, he is revered as a fighter for national identity against the Germans. There are many monuments to him, a large number of museums and streets are named after Jan Hus.

In 1915, in the center of Prague on Old Town Square (an ancient square located in the historical part of the city, Stare Mesto), a monument to Jan Hus was erected on the day of the 500th anniversary of his execution.

Jan Hus was mentioned more than once in poetry. Taras Shevchenko wrote his poem “The Heretic” about him, Fyodor Tyutchev dedicated the poem “Hus at the stake” to him, Yevgeny Yevtushenko recalled Jan Hus along with Pushkin and Petofi in his work “Tanks are marching through Prague...”