My first friend, my priceless friend!

And I blessed fate

When my yard is secluded

covered in sad snow,

Your bell has rung.

Analysis of Pushkin's poem "I. I. Pushchin»

Among his lyceum friends, Alexander Pushkin especially singled out Ivan Pushchin, with whom the poet had a very warm and trusting relationship. The two young people were united not only by common views on life, but also by a love of literature. In their youth, they even competed among themselves on the subject of who would write a poem on a given topic faster and better.

The fate of Ivan Pushchin was tragic. He was one of the participants in the Decembrist uprising, after the failure of which he received life imprisonment. The last time the friends met was just on the eve of these tragic events, in the winter of 1825. At this time, Pushkin lived in the Mikhailovskoye family estate, where, by order of the authorities, he was exiled for freethinking. And Pushchin was one of the first to visit the poet during this difficult period for him. The meeting of friends was short, but its meaning became clear to Pushkin much later, after the Decembrist uprising was ruthlessly suppressed, and his lyceum comrade was a prisoner of the Chita jail. Ivan Pushchin assumed such a development of events, so he came to Pushkin in order to say goodbye, although he did not say a word about the fact that he was to become one of the participants in a secret conspiracy and an attempt on the life of Emperor Nicholas I. This meeting of friends turned out to be the last, more was not destined to meet.

On the eve of the anniversary of the Decembrist uprising, in the winter of 1826, Pushkin wrote a poem called “I. I. Pushchin ”, which was transferred to the convict a few years later through the wife of the Decembrist Nikita Muravyov. In it, the poet recalls their last meeting, noting that he “blessed fate” when Ivan Pushchin came to him in Mikhailovskoye to brighten up loneliness and distract the author from gloomy thoughts about his own fate. In this moment best friend morally supported Pushkin, who was on the verge of despair, believing that his career was ruined, and his life was hopeless. Therefore, when Pushchin found himself in a similar situation, the author considered it his duty to send him an encouraging verse message, in which he confessed: “I pray to holy providence.” By this, the poet wanted to emphasize that he not only worries about the fate of his friend, but also believes that his sacrifice was not made to society in vain, and future generations will be able to appreciate this selfless act. At this time, the poet already knows that Ivan Pushchin refused to flee abroad after the failure of the Decembrist uprising and survived his arrest in his St. Petersburg house. Turning to a friend, the poet dreams that his voice, dressed in verse, will give him consolation. “May he illuminate the prison with a beam of lyceum clear days!”, Pushkin notes. Later, Ivan Pushchin wrote in his diary: "Pushkin's voice echoed in me with joy." Namely, this short message subsequently formed the basis of the memoirs of the former convict, which he dedicated to his friendship with the great Russian poet.

Pushkin was very upset by the separation from his friend, and subsequently addressed him a few more poems. Through his high-ranking acquaintances, he even tried to influence the decision of the authorities, hoping that the sentence of life imprisonment for Ivan Pushchin would still be mitigated. However, Emperor Nicholas I, who survived the horror of the assassination attempt on the day of his ascension to the throne, refused to pardon the Decembrist. Only after almost 30 years Ivan Pushchin received the right to return to St. Petersburg. He visited the grave of the poet, located on the territory of the Svyatogorsky monastery, as well as in Mikhailovsky, paying tribute to his lyceum friend, who did not turn away from him in difficult times.

My first friend, my priceless friend

190 years ago, the world's most famous poem about friendship was written.

I.I. Pushchino

My first friend

my friend is priceless!

And I blessed fate

When my yard is secluded

covered in sad snow,

Your bell has rung.

I pray holy Providence:

Yes, my voice to your soul

Gives the same comfort

May he illuminate the prison

Beam lyceum clear days!

Alexander Pushkin 1826

The friends met in Mikhailovsky at eight o'clock in the morning on January 11 (23rd according to the new style), 1825, and spent the whole day, evening and part of the night in conversation.

The arrival of Pushchin was a huge event for the disgraced poet. After all, even relatives did not dare to visit the exile, they dissuaded Pushchin from the trip.

The unexpected joy of the meeting illuminated not only that short January day, but also much that awaited friends ahead. When, thirty years later, Ivan Ivanovich Pushchin takes up his pen to describe his meeting with Pushkin in Mikhailovsky, every letter in his manuscript will shine with happiness. "Notes on Pushkin" is one of the brightest works created in the memoir genre in Russian.

Shortly before parting, friends remembered how they talked through a thin wooden partition in the Lyceum. Pushchin had the thirteenth room, Pushkin had the fourteenth. It's right in the middle of a long corridor. From a boyish point of view, the location is advantageous ─ while the tutor is coming from one end or the other, the neighbors will warn you of the danger. And Pushkin and Pushchin had a common window, a partition divided it strictly in half.

Reviews of the overseer Martyn Piletsky about the lyceum students have been preserved, here is what he wrote about the 13-year-old Pushchin:

"... Nobility, good nature with courage and subtle ambition, especially prudence ─ are his excellent qualities."

Who could have known then how useful Ivan would be both this courage and this prudence ...

The thirteenth number brought three bottles of Clicquot champagne, the manuscript "Woe from Wit", a letter from Ryleev, gifts from Uncle Vasily Lvovich, a lot of news to Mikhailovskoye, and took away the beginning of the poem "Gypsies", letters ... He left after midnight, at three o'clock January 12th.

"... The coachman had already harnessed the horses, the bell rang at the porch, the clock struck three. We still clinked glasses, but we drank sadly: as if it was felt that we were drinking together for the last time, and drinking for eternal separation! Silently I threw a fur coat over my shoulders and ran away in a sleigh. Pushkin was still saying something after me; not hearing anything, I looked at him: he stopped on the porch with a candle in his hand. The horses rushed downhill. I heard: "Farewell, friend!" .."

When Pushkin undertakes to complete his message to Pushchin, he will have been in prison for almost a year ─ first in the Peter and Paul Fortress, and then in the Shlisselburg Fortress. After the verdict, Ivan Pushchin and Wilhelm Küchelbecker were deleted from the "Memorial book of the Lyceum", as if they did not exist at all.

In October 1827, Pushchin, shackled in hand and foot shackles, was sent by stage to the Chita jail. The journey took three months.

"On the very day of my arrival in Chita, Alexandra Grigoryevna Muravyova calls me to the stockade and gives me a piece of paper on which it was written in an unknown hand: "My first friend, my priceless friend! .."

This was early in 1828. And Pushchin saw the original poem only in 1842.

Dmitry Shevarov "Motherland", No. 5, 2016

Illustration ─ Nikolai Ge. "Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin in the village of Mikhailovsky" (1875): Pushkin and Pushchin reading "Woe from Wit".

Yuri Markovich Nagibin

My first friend, my priceless friend

We lived in the same building, but didn't know each other. Not all the guys in our house belonged to the yard freemen. Other parents, protecting their children from the pernicious influence of the court, sent them for a walk to the grand garden at the Lazarev Institute or to the church garden, where old pawled maples overshadowed the tomb of the boyars Matveevs.

There, languishing from boredom under the supervision of decrepit devout nannies, the children stealthily comprehended the secrets about which the court spoke at the top of its voice. Fearfully and greedily they sorted out the rock inscriptions on the walls of the boyar tomb and the pedestal of the monument to the state councilor and cavalier Lazarev. My future friend, through no fault of his own, shared the fate of these miserable, greenhouse children.

All the children of the Armenian and adjacent lanes studied in two adjacent schools, on the other side of Pokrovka. One was in Starosadsky, next to the German church, the other - in Spasoglinishevsky Lane. I was not lucky. In the year I entered, the influx was so great that these schools could not accept everyone. With a group of our guys, I ended up in school No. 40, very far from home, in Lobkovsky Lane, behind Chistye Prudy.

We immediately realized that we would have to solo. The Chistoprudnys reigned here, and we were considered strangers, uninvited aliens. Over time, everyone will become equal and united under the school banner. At first, a healthy instinct for self-preservation kept us in a tight group. We united at breaks, went to school in a group and returned home in a group. The most dangerous was the crossing of the boulevard, here we kept the military formation. Having reached the mouth of Telegraph Lane, they relaxed somewhat, behind Potapovsky, feeling completely safe, they began to fool around, yell songs, fight, and, with the onset of winter, start dashing snow battles.

In the Telegraph I first noticed this long, thin, pale freckled boy with large gray-blue eyes half a face wide. Standing aside and tilting his head to his shoulder, he observed our valiant amusements with quiet, unenvious admiration. He shuddered a little when a snowball, thrown by a friendly but alien to condescension hand, covered someone's mouth or eye socket, smiled sparingly at especially outrageous antics, a faint blush of constrained excitement painted his cheeks. And at some point, I caught myself screaming too loudly, gesticulating exaggeratedly, feigning inappropriate, out of play, fearlessness. I realized that I was exhibiting myself in front of a strange boy, and I hated him. Why is he rubbing near us? What the hell does he want? Has he been sent by our enemies? .. But when I expressed my suspicions to the guys, they laughed at me:

Have you eaten henbane? Yes, he is from our house! ..

It turned out that the boy lives in the same building as me, on the floor below, and studies at our school, in a parallel class. It's amazing we never met! I immediately changed my attitude towards the grey-eyed boy. His imaginary stubbornness turned into subtle delicacy: he had the right to keep company with us, but did not want to impose himself, patiently waiting to be called. And I took it upon myself.

During another snow fight, I started throwing snowballs at him. The first snowball that hit him on the shoulder embarrassed and seemed to upset the boy, the next caused an indecisive smile on his face, and only after the third did he believe in the miracle of his communion and, grabbing a handful of snow, fired a return shell at me. When the fight was over, I asked him:

Do you live below us?

Yes, the boy said. - Our windows overlook the Telegraph.

So you live near Aunt Katya? Do you have one room?

Two. The second is dark.

We also. Only light goes to the trash. - After these secular details, I decided to introduce myself. - My name is Yura, and yours?

And the boy said:

... Tom is forty-three years old ... How many acquaintances there were then, how many names sounded in my ears, nothing compares to that moment when, in a snow-covered Moscow lane, a lanky boy quietly called himself: Pavlik.

What a reserve of individuality this boy, then a young man, had - he did not happen to become an adult - if he managed to enter so firmly into the soul of another person, by no means a prisoner of the past, with all his love for his childhood. There are no words, I am one of those who willingly evokes the spirits of the past, but I do not live in the darkness of the past, but in the harsh light of the present, and Pavlik is not a memory for me, but an accomplice in my life. Sometimes the feeling of his continuing existence in me is so strong that I begin to believe: if your substance has entered the substance of the one who will live after you, then you will not die completely. Let this not be immortality, but still a victory over death.

I know I can't really write about Pavlik yet. And I don't know if I'll ever be able to write. A lot of things are incomprehensible to me, well, at least what the death of twenty-year-olds means in the symbolism of being. And yet he should be in this book, without him, in the words of Andrei Platonov, the people of my childhood are incomplete.

At first, our acquaintance meant more to Pavlik than to me. I was already tempted in friendship. In addition to ordinary and good friends, I had a bosom friend, dark-haired, thick-haired, cut like a girl, Mitya Grebennikov. Our friendship began at a tender age, three and a half years old, and at the time described was five years old.

Mitya was a resident of our house, but a year ago his parents changed the apartment. Mitya ended up next door, in a large six-story building on the corner of Sverchkovo and Potapovsky, and was terribly proud. The house was, however, anywhere, with luxurious front doors, heavy doors and a spacious smooth elevator. Mitya, tirelessly, boasted of his house: “When you look at Moscow from the sixth floor ...”, “I don’t understand how people do without an elevator ...”. I delicately reminded him that just recently he lived in our house and got along just fine without an elevator. Looking at me with moist, dark eyes like prunes, Mitya said disgustedly that this time seemed to him a terrible dream. This should have been punched in the face. But Mitya not only looked like a girl in appearance - he was weak-hearted, sensitive, tearful, capable of hysterical outbursts of rage - and a hand was not raised against him. And yet, I gave it to him. With a heart-rending roar, he grabbed a fruit knife and tried to stab me. However, as a womanly quick-witted, he climbed to put up almost the next day. “Our friendship is greater than ourselves, we have no right to lose it” - these are the phrases he knew how to bend, and even worse. His father was a lawyer, and Mitya inherited the gift of eloquence.

Our precious friendship almost collapsed on the very first day of school. We ended up in the same school, and our mothers took care to seat us at the same desk. When they chose class self-government, Mitya offered me to be a nurse. And I did not name him when they put forward candidates for other public posts.

I. I. Pushchin

Notes

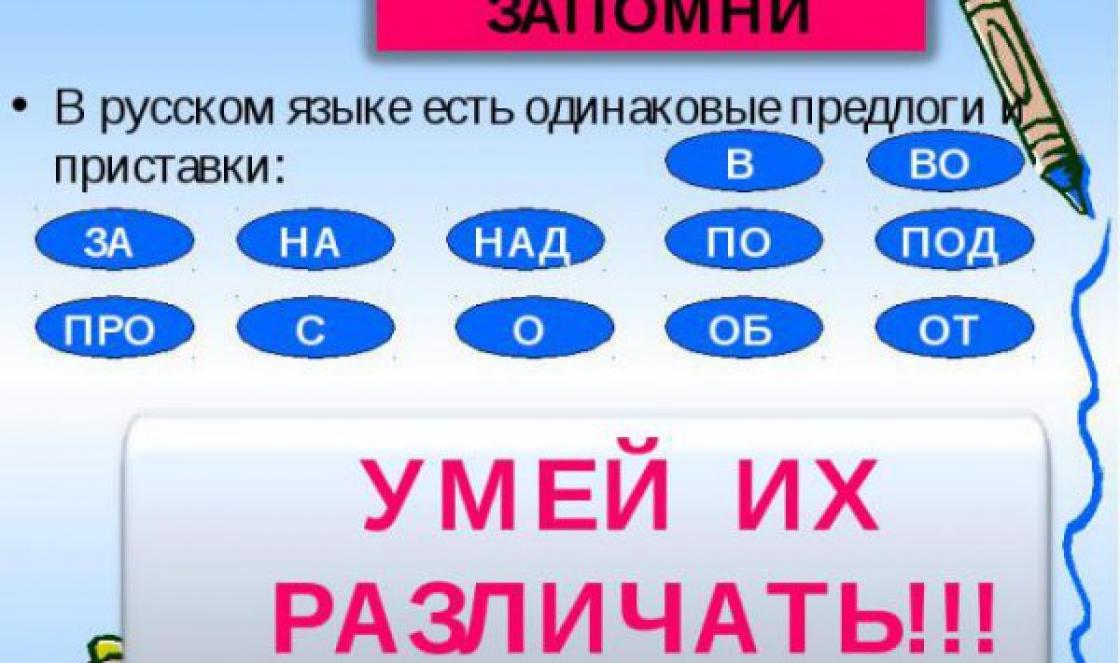

I. I. PUSHCHIN. My first friend, my priceless friend!. It was not published during Pushkin's lifetime. Written December 13, 1826, in Pskov.

The poem was sent to Pushchin in Siberia for hard labor along with a message to the Decembrists "In the depths of Siberian ores."

For the first stanza of this poem, Pushkin took without changes the first 5 verses of the unfinished message to Pushchin, written back in 1825. See "From early editions."

From earlier editions

In an unfinished message to I. I. Pushchin in 1825, the verse "Your bell has announced" followed:

Forgotten shelter, disgraced hut You suddenly revived with joy, On the deaf and distant side You shared the day of exile, the sad day With a sad friend. Tell me where the years have gone, Days of hope and freedom> Tell me what are ours? what friends? Where are these linden vaults? Where is youth? Where are you? Where I am? Fate, fate with an iron hand Has broken our peaceful lyceum, But you are happy, O dear brother, On your chosen line. You defeated prejudices And from grateful citizens You knew how to demand respect, In the eyes of public opinion You exalted the dark rank. In its humble foundation You observe justice, You honor ........... ...................

Unfinished message of 1825. The message was caused by Pushchin's arrival in Mikhailovskoye, where he spent one day with Pushkin. At the end of the message, it is said about the position of the judge, elected by Pushchin after his departure from the guard¤

The author talks about the beginning of everything in the life of every person. He insists that everything once happened to everyone for the first time. Suddenly, and for the first time in his life, a person meets another person. But we are also destined to tie our destinies for the rest of our lives. They become true friends.

The author tells about his faithful and devoted friend. His friend's name was Sasha. They met back in the kindergarten, but this meeting was very important and decisive for everyone. The author's friend had a very interesting appearance. He was thin, with huge green eyes. I always liked to be neat and neatly dressed. The friends loved spending time together. With pleasure each of them listened to the other.

Friends studied at different schools. Each of them had friends of classmates, but they never doubted that they were the closest friends and this was for life. The author compares their friendship with the friendship between Pushchin and Pushkin. He is glad that his friend is also called the Great Poet. The author is proud and rejoices in the strong friendship of two great people. He wants to take their example. He says that fate has not yet tested his friendship with Sasha, but he is sure that they will be able to overcome everything and maintain their devoted friendship.

Their relationship will be as strong and eternal as Pushkin and Pushchin.

Picture or drawing Nagibin My first friend, my priceless friend

Other retellings and reviews for the reader's diary

- Summary Ostrovsky Heart is not a stone

In a play main character- The young wife of a rich old man. Verochka is a pure, honest, but naive person. Everything is from inexperience, because it is always within four walls: at the mother’s, at the husband’s, to whom the shoemaker goes home.

- Summary of Chekhov Boys

The story of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov Boys tells of two high school students who came to New Year visiting the parents of one of the boys. They were going to run away to America on New Year's Eve

- Summary Chekhov Terrible Night

In the work of A.P. Chekhov's "Terrible Night" Ivan Petrovich Panikhidin tells the audience a story from his life. He visited séance at your friend's house

- Summary of Ushinsky Wind and Sun

The Sun and the Wind could not agree on which of them is the most powerful. We decided to test our strength on a lone traveler riding along the road.

- Summary of the tale Two frosts

The two brothers of Frost decided to have fun, to freeze people. Just then they saw that on one side the gentleman was riding, in a bearskin coat, and on the other side, a peasant was riding, in a torn short fur coat.