The Tale of Khoja Nasreddin is one of my favorite books. One of those that can be called ageless. That's great rarity! I never cling to the past - if I have “outgrown” a book, I will not return to it, I just remember the feelings that it gave in its time, and for this I am grateful to the author. But "Nasreddin" can be re-read at 10, and at 20, at 30, and at 60 years old - and there will be no feeling that he has outgrown.

In addition to all the joys that the Tale brings, it also contributed to the desire to go to Uzbekistan - a trip to Bukhara in 2007. was not just a trip to the old and beautiful city, I went to the homeland of Khoja Nasreddin. It was possible to look at the city in two ways: directly and through the prism of the book. And it is obvious that it makes sense to come to Bukhara again.

In the light of everything written above, it is all the more strange that no matter how many editions of the Tale fell into the hands, practically nothing was written in them about the author - Leonid Solovyov. A very meager biography - a maximum of a couple of small paragraphs. Attempts to find more information were fruitless. Up to this day. I could not imagine, for example, that the second part of The Tale (like R. Shtilmark's The Heir from Calcutta) was written in the Stalinist camp, and that thanks to this Solovyov was not exiled to Kolyma ...

It so happened that Leonid Solovyov did not get into the memoirs of his contemporaries. There are only brief notes of the mother, sisters, wife, preserved in the archives, and even a sketch in the papers of Yuri Olesha. Even a normal, solid photo portrait cannot be found. There are only a few small home photographs. Random, amateur. Solovyov's biography is full of sharp turns, strong upheavals, which by no means always coincide with general historical ones.

He was born on August 19, 1906, in Tripoli (Lebanon). The fact is that the parents were educated in Russia at public expense. So they weren't rich. They had to work for a certain period of time where they were sent. They sent them to Palestine. Each separately. There they met and got married. The Russian Palestine Society set itself missionary goals. In particular, he opened schools in Russian for Arabs.

Vasily Andreevich and Anna Alekseevna taught at one of these schools. In the year of his son's birth, his father was a collegiate adviser, assistant inspector of the North Syrian schools of the Imperial Orthodox Palestinian Society (as it was fully called). Having served the prescribed term in a distant land, the Solovyovs returned to Russia in 1909. According to the official movements of the father until 1918, their place of residence was Buguruslan, then nearby was the Pokhvistnevo station of the Samara-Zlatoust railway. Since 1921 - Uzbekistan, the city of Kokand.

There, Leonid studied at school and a mechanical college, without finishing it. Started working there. At one time he taught various subjects at the school of the FZU of the oil industry. Started writing. Began to be published in newspapers. He rose to Pravda Vostoka, which was published in Tashkent. He distinguished himself at the competition, which was announced by the Moscow magazine "World of Adventures". The story "On the Syr-Darya Shore" appeared in this magazine in 1927.

1930 Solovyov leaves for Moscow. He enters the literary and scriptwriting department of the Institute of Cinematography (VGIK). Finished it in June 1932. The dates found in Solovyov's biography are sometimes surprising. But the document on graduation from the institute has been preserved in the archive. Yes, Solovyov studied from the thirtieth to the thirty-second!

His first stories and stories about today's life, new buildings, everyday work of people, about Central Asia did not go unnoticed. In 1935-1936, special articles were devoted to Solovyov by the magazines Krasnaya Nov and Literary Studies. Suppose, in Krasnaya Nov, A. Lezhnev admitted: “His stories are built up each time around one simple idea, like the pulp of a cherry around a bone”, “... his stories retain an intermediate form between everyday feuilleton and a story” and so on. Nevertheless, the article was called "About L. Solovyov", and this meant that he was recognized, introduced into the series.

After the publication of "Troublemaker" Leonid Vasilyevich became completely famous. In the February issue of "Literary Studies" for 1941, following the greetings to Kliment Voroshilov on his sixtieth birthday, there was a heading "Writers about their work." She was taken to Solovyov. He talked about his latest book. In a word, he moved forward firmly and steadily.

When the war began, Solovyov became a war correspondent for the Krasny Fleet newspaper. He writes a kind of modern prose epics: "Ivan Nikulin - Russian sailor", "Sevastopol stone". According to the scripts, films are staged one after another.

In September 1946 Solovyov arrested. Either he really annoyed someone, or there was a denunciation, or one led to another. He spent ten months in pre-trial detention. In the end, he admitted his guilt - of course, fictitious: the plan of a terrorist act against the head of state. He said something unflattering about Stalin. Apparently, he told his friends, but he was mistaken in them. Solovyov was not shot, because the idea is not yet the action. We were sent to the Dubravlag camp. His address was as follows: Mordovian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, Potma station, Yavas post office, mailbox LK 241/13.

According to the memoirs of fellow camper Alexander Vladimirovich Usikov, Solovyov was selected as part of the stage to Kolyma. He wrote to the head of the camp, General Sergeenko, that if he was left here, he would take up the second book about Khoja Nasreddin. The general ordered Solovyov to leave. And The Enchanted Prince was indeed written in the camp. Manuscripts have been preserved. Papers, of course, were not given. She was sent by her family. Parents then lived in Stavropol, sisters - in various other cities.

Solovyov managed to become a night watchman in a workshop where wood was dried. Then he became a night attendant, that is, like a watchman at the bathhouse. Apparently, new prisoners were also brought in at night, they had to comply with sanitary standards. Occasionally, Moscow acquaintances were delivered. These meetings were great events in a monotonous life. Lonely night positions gave Solovyov the opportunity to concentrate on his literary pursuits.

The work on the book has been delayed. Still, by the end of 1950, The Enchanted Prince was written and sent to the authorities. The manuscript was not returned for several years. Solovyov was worried. But someone saved the "Enchanted Prince" - by accident or being aware of what was being done.

For reasons unclear to the biographer, apparently, in the middle of 1953 Solovyov's prison and camp life continued already in Omsk. Presumably, it was from there that he was released in June 1954, when all cases were reviewed. Among others, it became clear that Solovyov's accusation was exaggerated. I had to start life over.

For the first time, Leonid Vasilyevich married very early, back in Central Asia, in Kanibadam, Elizaveta Petrovna Belyaeva. But their paths soon parted. The Moscow family was Tamara Alexandrovna Sedykh. According to eyewitness accounts, their union was not smooth, or rather painful. Upon Solovyov's arrival from the camp, Sedykh did not take him back into the house. All letters were returned unopened. Solovyov had no children.

In the first days after the camp he was met in Moscow by Yuri Olesha. The Central Archive of Literature and Art (TsGALI) keeps a record of this meeting: “July 13. I met Leonid Solovyov, who returned from exile ("Troublemaker"). Tall, old, lost his teeth. (…) Decently dressed. This, he says, was bought by a man who owes him. I went to the department store and bought it. He says about life there that he did not feel bad - not because he was placed in any special conditions, but because inside, as he says, he was not in exile. “I took it as retribution for the crime I committed against one woman - my first, as he put it, “real wife.” Now I believe I'll get something."

Confused, confused, with bitter reproaches to himself, without money, where was he to go? On reflection, Leonid Vasilyevich went to Leningrad for the first time in his life, to his sister Zinaida (the eldest, Ekaterina, lived until the end of her days in Central Asia, in Namangan). Zina was tight. Lived with difficulty. In April 1955, Solovyov married Maria Markovna Kudymovskaya, a teacher of the Russian language, most likely his age. They lived on Kharkovskaya Street, building 2, apartment 16. There, in the last months of his life, I met Leonid Vasilyevich and I, unexpectedly learning that the author of The Tale of Khoja Nasreddin lives in Leningrad.

Everything seemed to be on the mend. Lenizdat was the first to publish The Enchanted Prince, preceded by The Troublemaker. The book was a huge success. Solovyov again began to work for the cinema. Started The Book of Youth. But health was deteriorating. He had severe hypertension. I found Leonid Vasilyevich walking, but half of his body was paralyzed. On April 9, 1962, he died before reaching fifty-six.

At first, in Leningrad, Solovyov was immediately supported by Mikhail Aleksandrovich Dudin. We also met friendly people. But in Leningrad literary life Leonid Vasilievich did not really enter. He kept himself apart - most likely due to ill health and mental unrest. When Maria Markovna gathered writers at her place to celebrate some date connected with Solovyov, there were three of us and one more, who did not know Leonid Vasilyevich. He was buried at the Red Cemetery in Avtovo.

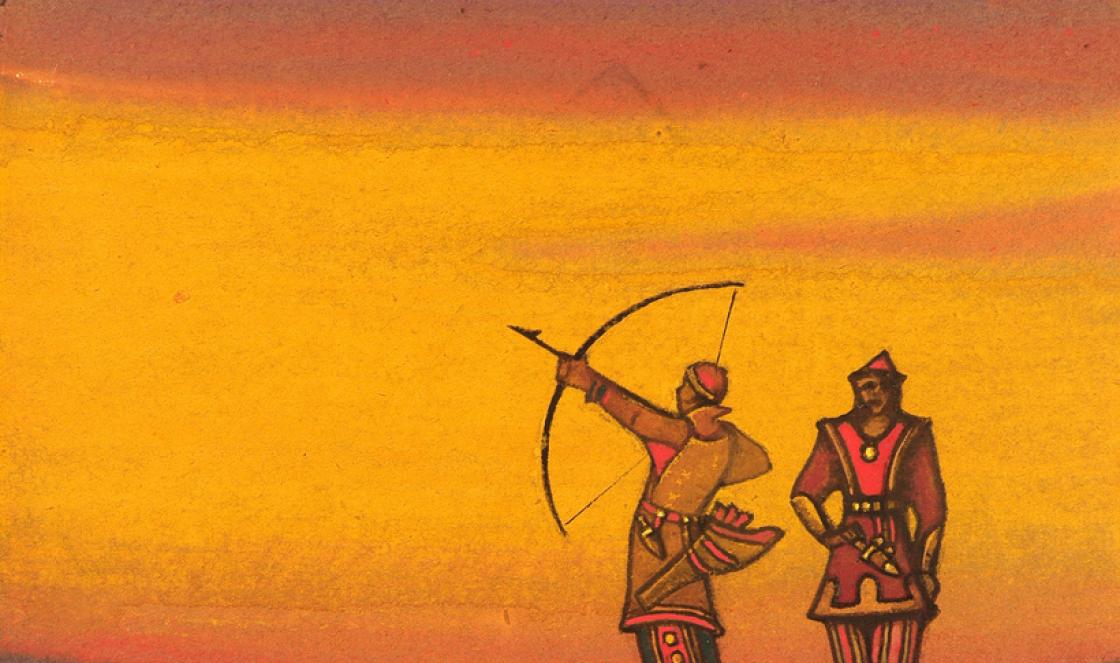

Monument to Khoja Nasreddin in Bukhara

P.S. In 2010, the complete works of Leonid Solovyov were published in 5 volumes. Publishing House "Book Club Knigovek".

All day the sky was covered with a gray veil. It became cold and deserted. The dull treeless steppe plateaus with burnt-out grass made me sad. Went to sleep...

In the distance appeared the post of the TRF the Turkish equivalent of our traffic police. I instinctively prepared for the worst, because I know from past driving experience that meetings with such services do not bring much joy.

I have not had to deal with Turkish "road owners" yet. Are they the same as ours? Just in case, in order not to give the road guards time to come up with an excuse to find fault with us, they stopped themselves and “attacked” them with questions, remembering that the best defense is an attack.

But, as we have seen, there is a completely different “climate”, and the local “traffic cops”, in whom drivers are accustomed to seeing their eternal opponents, were not at all going to stop us and were not at all opponents of motorists. Even vice versa.

The police kindly answered our questions, gave a lot of advice, and in general showed the liveliest interest in us and especially in our country. Already a few minutes of conversation convinced me: these are simple, disinterested and kind guys, conscientiously fulfilling their official duty, which at the same time does not prevent them from being sympathetic, cheerful and smiling. The hospitable policemen invited us to their post to drink a glass of tea and continue the conversation there...

After this fleeting meeting, it seemed to me that the sky seemed to brighten up, and it became warmer, and nature smiled ... And it was as if the shadow of that cheerful person who, according to the Turks, once lived here, flashed by.

We were approaching the city of Sivrihisar. The surroundings are very picturesque - rocky mountains, bristling up to the sky with sharp teeth. From a distance, I was mistaking them for ancient fortress walls. Apparently, the city was named “Sivrihisar”, which means “fortress with pointed walls”. At the entrance to the city, to the left of the highway, they suddenly saw a monument an old man in a wide-brimmed hat is sitting on a donkey, thrusting a long stick into the globe, on which is written: “Dunyanyn merkezi burasydyr” (“The center of the world is here”).

I was waiting for this meeting and therefore I immediately guessed: this is the legendary Nasreddin-Khoja ...

I remembered an anecdote. Nasreddin was asked a tricky question that seemed impossible to answer: "Where is the center of the Earth's surface?" “Here,” Hodge replied, sticking his stick into the ground. If you don’t believe me, you can make sure I’m right by measuring the distances in all directions...”

But why is this monument erected here? We turn into the city and at the hotel, which is called "Nasreddin-Khoja", we learn that, it turns out, one of the neighboring villages is no more, no less the homeland of the favorite of the Turks.

This further piqued our curiosity. Immediately we go to the specified village. Today it is also called Nasreddin-Khoja. And at the time when Nasreddin was born there, her name was Hortu.

Three kilometers from the road leading to Ankara, a roadside sign made us turn sharply to the southwest.

Along the main street of the village there are whitewashed blank end walls of adobe houses, painted with color paintings illustrating jokes about Nasreddin. On the central square, which, like the main street in this small village, can only be called so conditionally, a small monument has been erected. On the pedestal there is an inscription testifying that Nasreddin was born here in 1208 and lived until the age of 60. He died in 1284 in Aksehir...

The headman pointed out to us a narrow, crooked street, where one car could not pass, that was where Nasreddin's house was. The huts huddle closely, clinging to each other. Walls without windows that had grown into the ground, like blind old men crushed by the unbearable burden of time, were powdered with whitewash, which, contrary to their aspirations, did not hide age, but, on the contrary, showed wrinkles even more. The same miserable and compassionate crooked doors and gates squinted and wrinkled from old age and disease... Some houses were two stories high; the second floors hung like bony loggias over crooked steep streets.

Nasreddin's dwelling differs from others in that the house was built not immediately outside the gate, at the "red line", but in the depths of a tiny "patch" courtyard, at the back border of the site. Cramped on both sides by neighbors, a dilapidated house, built of unhewn stones, nevertheless contained several small rooms and an open veranda on the second floor. In the lower floor utility rooms and for the traditional personal transport of the East the unchanging donkey. In an empty courtyard without a single tree, only an antediluvian axle from a cart with wooden solid curved wheels has been preserved.

No one has lived in the house for a long time, and it has fallen into complete disrepair. However, they say, as a token of grateful memory to the glorious Nasreddin, a new, solid house worthy of his on the main square will be built in his native village. And then the villagers are ashamed that their illustrious countryman has such a wreck ... And, right, they will hang a memorial plaque on that house with the inscription: "Nasreddin-Khoja was born and lived here."

Such a neglected view of his house surprised us a lot: the popularity of Nasreddin-Khoja has reached truly global proportions. With the growth of his popularity, the number of applicants who considered Nasreddin their countryman also grew. Not only the Turks, but also many of their neighbors in the Middle East, the Caucasus, and Central Asia consider him “their own” ...

Such a neglected view of his house surprised us a lot: the popularity of Nasreddin-Khoja has reached truly global proportions. With the growth of his popularity, the number of applicants who considered Nasreddin their countryman also grew. Not only the Turks, but also many of their neighbors in the Middle East, the Caucasus, and Central Asia consider him “their own” ...

Nasreddin's grave is located in the city of Akshehir, about two hundred kilometers south of his native village. It is curious that the date of death on the tombstone of the crafty merry fellow and joker, as they say, is also deliberately indicated in a playful spirit, in his manner backwards (this is how Nasreddin-Khoja often rode his donkey) that is, 386 instead of 683, which corresponds to 1008 according to our chronology. But ... it turns out then that he died before he was born! True, this kind of "inconsistency" does not bother the fans of the beloved hero.

I asked the inhabitants of Nasreddin-Khoja whether any of the descendants of the Great Joker had accidentally remained here. It turned out that there are descendants. In less than five minutes, the neighbors, without hesitation, introduced us to the direct descendants of Nasreddin, whom we captured against the backdrop of a historic dwelling ...

favorite of Nasreddin

Alternative descriptionsPet

Donkey, hinny or mule

The person who does the minimum work for the maximum reward

Beast of burden

long-eared transport

Transport Nasreddin

Asian "horse"

Donkey with Central Asian ornament

Stubborn Stubborn

hard-working donkey

donkey hard worker

industrious animal

cargo cattle

Cattle with a bale on their back

Living "truck" Asian

Resigned hard worker

Same donkey

Skotina Nasreddin

Shurik's eared transport

Donkey with an Asian bias

Workaholic Donkey

Donkey plowed

. Asian "truck"

. "motor" arba

Horse_Nasred-_din

Nasredin taught him to speak

Donkey harnessed to a cart

Domesticated African donkey

Stubborn

Horse Nasreddin

Animal Nasreddin

Central Asian version of Winnie the Pooh's friend

pet in the middle east

Same as donkey

Donkey from Central Asia

Asian Donkey

Donkey in the expanses of Central Asia

hoofed pet

Donkey in Asia

. “Looking for porridge from the mother-in-law” (palindrome)

Donkey who moved to Central Asia

working donkey

Transport of cunning Khoja Nasreddin

Central Asian donkey

donkey workaholic

Donkey of Central Asian nationality

Horse Khoja Nasreddin

Eared stubborn workaholic

Donkey hard worker

Asian cattle

Central Asian pet

Arba engine

industrious donkey

laborious donkey

eared hard worker

Stubborn Beast

He is a donkey

Four-legged cart tractor

Donkey that drags a cart

hardworking donkey

working animal

working donkey

What animal can stubbornly?

. "tractor" for arba

What animal can kick?

What animal is harnessed to the cart?

Horse plus donkey

diligent donkey

Eastern name for donkey

. "tractor" arba

Donkey or mule

Horse and donkey mix

Pet, donkey or mule

The man who does the hardest work without a murmur

Donkey and Regio hinny or mule

Stubborn Stubborn

. "Looking for porridge from the mother-in-law" (palind.)

. "Transport" Nasreddin

. "Tractor" carts

. "Tractor" for arba

. asian truck

. "Looking for porridge from his mother-in-law" (palindrome)

. "motor" arba

Asian "horse"

Live "truck" Asian

What animal is harnessed to the cart

What animal can kick

What animal can stubbornly

M. tatarsk. sib. orenb. kavk. donkey; donkey, donkey donkey; donkey, donkey m. donkey foal; in some places, the donkey is called both the hinny and the mule, even the mashtak, a small horse. Either a donkey, or an ishan, that is, not all the same: either a donkey, or a Muslim clergyman. donkey, donkey, belonging to the donkey., related

Donkey middle-az. nationality

Wed-az. donkey

Another name for donkey

. "Skakun" in a cart cart

Donkey harnessed to a cart

O. BULANOVA

There is probably not a single person who has not heard of Khoja Nasreddin, especially in Muslim East. His name is remembered in friendly conversations, in political speeches, and in scientific disputes. They remember for various reasons, and even for no reason at all, simply because Hodge has been in all conceivable and unthinkable situations in which a person can find himself: he deceived and was deceived, cunning and getting out, was immensely wise and a complete fool.

For so many years he joked and mocked human stupidity, self-interest, complacency, ignorance. And it seems that stories in which reality goes hand in hand with laughter and paradox are almost not conducive to serious conversations. If only because this person is considered a folklore character, fictional, legendary, but in no way historical figure. However, just as seven cities argued for the right to be called the homeland of Homer, so three times as many peoples are ready to call Nasreddin theirs.

Nasreddin was born in the family of the venerable Imam Abdullah in the Turkish village of Khorto in 605 AH (1206) near the city of Sivrihisar in the province of Eskisehir. However, dozens of villages and cities in the Middle East are ready to argue about the nationality and birthplace of the great cunning.

In maktab, an elementary Muslim school, little Nasreddin asked his teacher - domullah - tricky questions. The domulla simply could not answer many of them. Then Nasreddin studied in Konya, the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate, lived and worked in Kastamonu, then in Aksehir, where, in the end, he died.

Turkish professor-historian Mikayil Bayram conducted an extensive study, the results of which showed that the full name of the real prototype of Nasreddin is Nasir ud-din Mahmud al-Khoyi, he was born in the city of Khoy, Iranian province of Western Azerbaijan, was educated in Khorasan and became a student of the famous Islamic figure Fakhr ad-din ar-Razi.

Caliph of Baghdad sent him to Anatolia to organize resistance Mongol invasion. He served as a qadi, an Islamic judge, in Kayseri and later became a vizier at the court of Sultan Kay-Kavus II in Konya. He managed to visit a huge number of cities, got acquainted with many cultures and was famous for his wit, so it is quite possible that he was the first hero of funny or instructive stories about Khoja Nasreddin.

True, it seems doubtful that this educated and influential person rode around on a modest donkey and quarreled with his quarrelsome and ugly wife. But what a noble cannot afford is quite accessible to the hero of funny and instructive anecdotes, isn't it?

However, there are other studies that admit that the image of Khoja Nasreddin is a good five centuries older than is commonly believed in modern science.

An interesting hypothesis was put forward by Azerbaijani scientists. A number of comparisons allowed them to assume that the famous Azerbaijani scientist Haji Nasireddin Tusi, who lived in the 13th century, was the prototype of Nasreddin. Among the arguments in favor of this hypothesis is, for example, the fact that in one of the sources Nasreddin is called by this name - Nasireddin Tusi.

In Azerbaijan, Nasreddin's name is Molla - perhaps this name, according to researchers, is a distorted form of the name Movlan, which belonged to Tusi. He had another name - Hassan. This point of view is confirmed by the coincidence of some motifs from the works of Tusi himself and anecdotes about Nasreddin (for example, ridicule of soothsayers and astrologers). The considerations are interesting and not without persuasiveness.

Thus, if you start looking in the past for a person similar to Nasreddin, it will very soon become clear that his historicity borders on legendary. However, many researchers believe that traces of Khoja Nasreddin should not be sought in historical chronicles and grave crypts, which, judging by his character, he did not want to get into, but in those parables and anecdotes that were told and are still being told by the peoples of the Middle East and Central Asia, and not only them.

Folk tradition draws Nasreddin truly many-sided. Sometimes he appears as an ugly, unsightly man in an old, worn dressing gown, in the pockets of which, alas, there are too many holes for something to be stale. Why, sometimes his dressing gown is simply greasy with dirt: long wanderings and poverty take their toll. At another time, on the contrary, we see a person with a pleasant appearance, not rich, but living in abundance. In his house there is a place for holidays, but there are also black days. And then Nasreddin sincerely rejoices at the thieves in his house, because finding something in empty chests is a real success.

Khoja travels a lot, but it is not clear where is his home after all: in Akshehir, Samarkand, Bukhara or Baghdad? Uzbekistan, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Armenia (yes, she too!), Greece, Bulgaria are ready to give him shelter. His name is inclined to different languages: Khoja Nasreddin, Jokha Nasr-et-din, Mulla, Molla (Azerbaijani), Afandi (Uzbek), Ependi (Turkmen), Nasyr (Kazakh), Anasratin (Greek). Friends and students are waiting for him everywhere, but there are also enough enemies and ill-wishers.

The name Nasreddin is spelled differently in many languages, but they all go back to the Arabic Muslim personal name Nasr ad-Din, which translates as "Victory of the Faith." In different ways and address Nasreddin in parables different peoples- it can be a respectful address “Khoja”, and “Molla”, and even the Turkish “effendi”. It is characteristic that these three appeals - khoja, molla and efendi - are in many ways very close concepts.

Compare yourself. “Khoja” in Farsi means “master”. This word exists in almost all Turkic languages, as well as in Arabic. Initially, it was used as the name of the clan of the descendants of Islamic Sufi missionaries in Central Asia, representatives of the “white bone” estate (Turk. “ak suyuk”). Over time, “Khoja” became an honorary title, in particular, Islamic spiritual mentors of Ottoman princes or teachers of Arabic literacy in a mekteb, as well as noble husbands, merchants or eunuchs in ruling families, began to be called this way.

Mulla (molla) has several meanings. For Shiites, a mullah is the leader of a religious community, a theologian, a specialist in interpreting issues of faith and law (for Sunnis, these functions are performed by the ulema). In the rest of the Islamic world, in a more general sense, as a respectful title, it can mean: “teacher”, “assistant”, “owner”, “protector”.

Efendi (afandi, ependi) (this word has Arabic, Persian, and even ancient Greek roots) means “one who can (in court) defend himself”). This is an honorary title of noble people, a polite treatment with the meanings “master”, “respected”, “master”. Usually followed the name and was given mainly to representatives of scientific professions.

But back to the reconstructed biography. Khoja has a wife, son and two daughters. The wife is a faithful interlocutor and eternal opponent. She is grumpy, but sometimes much wiser and calmer than her husband. His son is completely different from his father, and sometimes he is just as cunning and troublemaker.

Khoja has many professions: he is a farmer, a merchant, a doctor, a healer, he even trades in theft (most often unsuccessfully). He is a very religious person, so his fellow villagers listen to his sermons; he is fair and knows the law well, therefore he becomes a judge; he is majestic and wise - and now the great emir and even Tamerlane himself want to see him as his closest adviser. In other stories, Nasreddin is a stupid, narrow-minded person with many shortcomings and is even sometimes reputed to be an atheist.

One gets the impression that Nasreddin is a manifestation human life in all its diversity, and everyone can (if he wants) discover his own Nasreddin.

It can be concluded that Khoja Nasreddin is, as it were, a different outlook on life, and if certain circumstances cannot be avoided, no matter how hard you try, then you can always learn something from them, become a little wiser, and therefore much freer from these very circumstances! And maybe, at the same time, it will turn out to teach someone else ... or teach a lesson. Nasreddin will definitely not rust.

For the Arab tradition, Nasreddin is not an accidental character. It is not at all a secret that every fable or anecdote about him is a storehouse of ancient wisdom, knowledge about the path of a person, about his destiny and ways of gaining a true existence. And Hoxha is not just an eccentric or an idiot, but someone who, with the help of irony and paradox, tries to convey high religious and ethical truths.

It can be boldly concluded that Nasreddin is a real Sufi! Sufism is an internal mystical trend in Islam that developed along with official religious schools. However, the Sufis themselves say that this trend is not limited to the religion of the prophet, but is the seed of any genuine religious or philosophical teaching. Sufism is the striving for Truth, for the spiritual transformation of man; this is a different way of thinking, a different view of things, free from fears, stereotypes and dogmas. And in this sense, real Sufis can be found not only in the East, but also in Western culture.

The mystery that Sufism is shrouded in, according to its followers, is connected not with some special mysticism and secrecy of the teaching, but with the fact that there were not so many sincere and honest seekers of truth in all ages.

In our age, accustomed to sensations and revelations, these truths pale before stories of mystical miracles and world conspiracies, but it is about them that the sages speak. And with them Nasreddin. The truth is not far away, it is here, hidden behind our habits and attachments, behind our selfishness and stupidity.

The image of Khoja Nasreddin, according to Idris Shah, is an amazing discovery of the Sufis. Khoja does not teach or rant, there is nothing far-fetched in his tricks. Someone will laugh at them, and someone, thanks to them, will learn something and realize something. Stories live their lives, wandering from one nation to another, Hodge travels from anecdote to anecdote, the legend does not die, wisdom lives on.

Khoja Nasreddin constantly reminds us that we are limited in understanding the essence of things, and therefore in their assessment. And if someone is called a fool, there is no point in being offended, because for Khoja Nasreddin such an accusation would be the highest of praises! Nasreddin is the greatest teacher, his wisdom has long crossed the borders of the Sufi community. But few people know this Hodja.

In the East, there is a legend that says that if you tell seven stories about Khoja Nasreddin in a special sequence, then a person will be touched by the light of eternal truth, giving extraordinary wisdom and power. How many were those who from century to century studied the legacy of the great mockingbird, one can only guess.

Generations changed generations, fairy tales and anecdotes were passed from mouth to mouth throughout all the tea and caravanserai of Asia, the inexhaustible folk fantasy added to the collection of stories about Khoja Nasreddin all new parables and anecdotes that spread over a vast territory. The themes of these stories have become part of the folklore heritage of several peoples, and the differences between them are explained by the diversity national cultures. Most of them depict Nasreddin as a poor villager and have absolutely no reference to the time of the story - their hero could live and act in any time and era.

For the first time, the stories about Khoja Nasreddin were subjected to literary processing in 1480 in Turkey, being recorded in a book called “Saltukname”, and a little later, in the 16th century, by the writer and poet Jami Ruma Lamiya (died in 1531), the following manuscript with stories about Nasreddin dates back to 1571. Later, several novels and stories were written about Khoja Nasreddin (“Nasreddin and his wife” by P. Millin, “Rosary from cherry stones” by Gafur Gulyam, etc.).

Well, the 20th century brought the stories about Khoja Nasreddin to the movie screen and the theater stage. Today, the stories about Khoja Nasreddin have been translated into many languages and have long become part of the world's literary heritage. So, 1996-1997 was declared by UNESCO international year Khoja Nasreddin.

The main feature of the literary hero Nasreddin is to get out of any situation as a winner with the help of a word. Nasreddin, masterfully mastering the word, neutralizes any of his defeats. Hoxha's frequent tricks are feigned ignorance and the logic of the absurd.

The Russian-speaking reader knows the stories about Khoja Nasreddin not only from collections of parables and anecdotes, but also from the wonderful novels by Leonid Solovyov "Troublemaker" and "The Enchanted Prince", combined into "The Tale of Khoja Nasreddin", also translated into dozens of foreign languages.

In Russia, the “official” appearance of Khoja Nasreddin is associated with the publication of the “History of Turkey” by Dmitry Cantemir (Moldovan ruler who fled to Peter I), which included the first historical anecdotes about Nasreddin (Europe got to know him much earlier).

The subsequent, unofficial existence of the great Hoxha is shrouded in mist. Once, leafing through a collection of fairy tales and fables collected by folklorists in Smolensk, Moscow, Kaluga, Kostroma and other regions in the 60-80s of the last century, researcher Alexei Sukharev found several anecdotes that exactly repeat the stories of Khoja Nasreddin. Judge for yourself. Foma says to Yerema: “I have a headache, what should I do?”. Yerema replies: “When I had a toothache, I pulled it out.”

And here is Nasreddin's version. “Afandi, what should I do, my eye hurts?” a friend asked Nasreddin. “When I had a toothache, I could not calm down until I pulled it out. Probably, you should do the same, and you will get rid of the pain, ”advised Hoxha.

It turns out that this is nothing unusual. Such jokes can be found, for example, in the German and Flemish legends about Thiel Ulenspiegel, in Boccaccio's Decameron, in Cervantes' Don Quixote. Similar characters among other peoples: Sly Peter - among the southern Slavs; in Bulgaria there are stories in which two characters are present at the same time, competing with each other (most often - Khoja Nasreddin and Sly Peter, which is associated with the Turkish yoke in Bulgaria).

The Arabs have a very similar character Jokha, the Armenians have Pulu-Pugi, the Kazakhs (along with Nasreddin himself) have Aldar Kose, the Karakalpaks have Omirbek, Crimean Tatars- Akhmet-akai, among the Tajiks - Mushfiks, among the Uighurs - Salai Chakkan and Molla Zaydin, among the Turkmens - Kemine, among the Ashkenazi Jews - Hershele Ostropoler (Hershele from Ostropol), among the Romanians - Pekale, among the Azerbaijanis - Molla Nasreddin. In Azerbaijan, the satirical magazine Molla Nasreddin, published by Jalil Mammadguluzade, was named after Nasreddin.

Of course, it is difficult to say that the stories about Khoja Nasreddin influenced the appearance of similar stories in other cultures. Somewhere for researchers this is obvious, but somewhere it is not possible to find visible connections. But it is difficult not to agree that there is something unusually important and attractive in this.

Of course, there will definitely be someone who will say that Nasreddin is incomprehensible or simply outdated. Well, if Hodge happened to be our contemporary, he would not be upset: you can’t please everyone. Yes, Nasreddin did not like to get upset at all. The mood is like a cloud: it ran and flew away. We get upset only because we lose what we had. Now, if you lost them, then there is something to be upset about. As for the rest, Khoja Nasreddin has nothing to lose, and this, perhaps, is his most important lesson.

The article uses materials from the Bolshoi Soviet Encyclopedia(article “Khodja Nasreddin”), from the book “Good Jokes of Khoja Nasreddin” by Alexei Sukharev, from the book “Twenty-Four Nasreddins” (Compiled by M.S. Kharitonov)

Khoja Nasreddin is a folklore character of the Muslim East and some peoples of the Mediterranean and the Balkans, the hero of short humorous and satirical miniatures and anecdotes, and sometimes everyday tales. There are frequent statements about its existence in real life in specific places (for example, in the city of Aksehir, Turkey).

At the moment, there is no confirmed information or serious grounds to talk about the specific date or place of Nasreddin's birth, so the question of the reality of the existence of this character remains open.

On the territory of Muslim Central Asia and the Middle East, in Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Central Asian and Chinese literature, as well as in the literature of the peoples of the Transcaucasus and the Balkans, there are many popular anecdotes and short stories about Khoja Nasreddin. The most complete collection of them in Russian contains 1238 stories.

The literary character of Nasreddin is eclectic and combines the syncretic image of a sage and a simpleton at the same time.

This internally contradictory image of an anti-hero, a vagabond, a freethinker, a rebel, a fool, a holy fool, a cunning rogue, and even a cynic philosopher, a subtle theologian and a Sufi, clearly transferred from several folklore characters, ridicules human vices, misers, bigots, hypocrites, bribe-taking judges and mullah.

Often finding himself on the verge of violating generally accepted norms and concepts of decency, his hero, nevertheless, invariably finds an extraordinary way out of the situation.

The main feature of the literary hero Nasreddin is to get out of any situation as a winner with the help of a word. Nasreddin-effendi masterfully mastering the word, neutralizes any of his defeats. Hoxha's frequent tricks are feigned ignorance and the logic of the absurd.

An integral part of the image of Nasreddin was the donkey, which appears in many parables or as main character, or as a satellite of Hoxha.

The Russian-speaking reader is best known for Leonid Solovyov's dilogy The Tale of Khoja Nasreddin, which consists of two novels: The Troublemaker and The Enchanted Prince. This book has been translated into dozens of languages around the world.

Similar characters among other peoples: Sly Peter among the southern Slavs, Jokha among the Arabs, Pulu-Pugi among the Armenians, Aldar Kose among the Kazakhs (along with Nasreddin himself), Omirbek among the Karakalpaks, is also found in the epos of the Kazakhs (especially the southern ones) due to the kinship of languages and cultures, Akhmet-akai among the Crimean Tatars, Mushfike among the Tajiks, Salyai Chakkan and Molla Zaidin among the Uighurs, Kemine among the Turkmens, Til Ulenspiegel among the Flemings and Germans, Hershele from Ostropol among the Ashkenazi Jews.

As three hundred years ago, as in our days, jokes about Nasreddin are very popular among children and adults in many Asian countries.

Several researchers date the emergence of anecdotes about Khoja Nasreddin to the 13th century. If we accept that this character actually existed, then he lived in the same 13th century.

Academician V. A. Gordlevsky, a prominent Russian turkologist, believed that the image of Nasreddin came out of anecdotes created among the Arabs around the name of Juhi and passed to the Seljuks, and later to the Turks as its extension.

Other researchers are inclined to believe that both images have only a typological similarity, explained by the fact that almost every nation in folklore has a popular hero-wit, endowed with the most contradictory properties.

The first anecdotes about Khoja Nasreddin were recorded in Turkey in "Saltukname" (Saltukname), a book dating from 1480 and a little later in the 16th century by the writer and poet "Jami Ruma" Lamia (d. 1531).

Later, several novels and stories about Khoja Nasreddin were written (Nasreddin and his wife by P. Millin, Rosary from cherry stones by Gafur Gulyam, etc.).

In Russia, Hodge anecdotes first appeared in the 18th century, when Dmitry Cantemir, a Moldavian ruler who fled to Peter I, published his History of Turkey with three "historical" anecdotes about Nasreddin.

In Russian tradition, the most common name is Khoja Nasreddin. Other options: Nasreddin-efendi, molla Nasreddin, Afandi (Efendi, Ependi), Anastratin, Nesart, Nasyr, Nasr ad-din.

IN Oriental languages there are several different versions of the name Nasreddin, they all boil down to three main ones:

* Khoja Nasreddin (with variations in the spelling of the name "Nasreddin"),

* Mulla (Molla) Nasreddin,

* Afandi (effendi) (Central Asia, especially among the Uighurs and in Uzbekistan).

The Persian word "hoja" (Persian waga "master") exists in almost all Turkic and Arabic. In the beginning, it was used as the name of the clan of the descendants of Islamic Sufi missionaries in Central Asia, representatives of the “white bone” class (Turk. “ak suyuk”). Over time, “Khoja” became an honorary title, in particular, Islamic spiritual mentors of Ottoman princes or teachers of Arabic literacy in Makteb, as well as noble husbands, merchants or eunuchs in ruling families, began to be called this way.

The Arabic Muslim personal name Nasreddin translates to "Victory of the Faith".

Mulla (molla) (arab. al-mullaa, Turkish molla) has several meanings. For Shiites, a mullah is the leader of a religious community, a theologian, an expert in interpreting issues of faith and law (for Sunnis, these functions are performed by the ulema).

In the rest of the Islamic world, in a more general sense, as a respectful title, it can mean: “teacher”, “assistant”, “owner”, “protector”.

Efendi (afandi, ependi) (arab. Afandi; Persian from ancient Greek aphthentes "one who can (in court) defend himself") - an honorary title of noble persons, polite treatment, with the meanings "master", "respected", "mister". It usually followed the name and was given mainly to representatives of learned professions.

The most developed and, according to some researchers, the classic and original is the image of Khoja Nasreddin, which still exists in Turkey.

According to the documents found, a certain Nasreddin really lived there at that time. His father was Imam Abdullah. Nasreddin was educated in the city of Konya, worked in Kastamonu and died in 1284 in Aksehir, where his grave and mausoleum (Hoca Nasreddin turbesi) have been preserved to this day.

On the tombstone there is most likely an erroneous date: 386 Hijri (i.e. 993 AD). Perhaps it is incorrect because the Seljuks appeared here only in the second half of the 11th century. It is suggested that the great joker has a “difficult” grave, and therefore the date must be read backwards.

Other researchers dispute these dates. K. S. Davletov attributes the origin of the image of Nasreddin to the 8th-11th centuries. There are also a number of other hypotheses.

Monuments

* Uzbekistan, Bukhara, st. N. Khusainova, house 7 (as part of the Lyabi-Khauz architectural ensemble)

* Russia, Moscow, st. Yartsevskaya, 25a (next to Molodezhnaya metro station) - opened on April 1, 2006, sculptor Andrey Orlov.

* Türkiye, reg. Sivrihisar, s. Horta

There is probably not a single person who has not heard of Khoja Nasreddin, especially in the Muslim East. His name is remembered in friendly conversations, in political speeches, and in scientific disputes. They remember for various reasons, and even for no reason at all, simply because Hodge has been in all conceivable and unthinkable situations in which a person can find himself: he deceived and was deceived, cunning and getting out, he was immensely wise and a complete fool ...

And for almost a thousand years now he has been joking and mocking human stupidity, self-interest, complacency, ignorance. And it seems that stories in which reality goes hand in hand with laughter and paradox are almost not conducive to serious conversations. If only because this person is considered a folklore character, fictional, legendary, but not a historical figure. However, just as seven cities argued for the right to be called the homeland of Homer, so three times as many peoples are ready to call Nasreddin theirs.

Scientists different countries they are searching: did such a person really exist and who was he? Turkish researchers believe that this person is historical, and insisted on their version, although they had not much more reason than scientists of other nations. We just decided that, that's all. Quite in the spirit of Nasreddin himself ...

Not so long ago, information appeared in the press that documents were found that mention the name of a certain Nasreddin. Having compared all the facts, you can bring them together and try to reconstruct the biography of this person.

Nasreddin was born in the family of the venerable Imam Abdullah in the Turkish village of Khorto in 605 AH (1206) near the city of Sivrihisar in the province of Eskisehir. However, dozens of villages and cities in the Middle East are ready to argue about the nationality and birthplace of the great cunning.

In maktabe, an elementary Muslim school, little Nasreddin asked his teacher - domulla - tricky questions. The domulla simply could not answer many of them.

Then Nasreddin studied in Konya, the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate, lived and worked in Kastamonu, then in Aksehir, where, in the end, he died. In Aksehir, his grave is still shown, and there is also an annual International Festival Khoja Nasreddin.

With the date of death is even more confusion. It can be assumed that if a person is not sure where he was born, then he does not know where he died. However, there is a grave and even a mausoleum - in the area of the Turkish city of Akshehir. And even the date of death on the gravestone of the tomb is indicated - 386 AH (993). But, as a prominent Russian turkologist and academician V.A. Gordlevsky, for a number of reasons, "this date is absolutely unacceptable." Because it turns out that Hodge died two hundred years before his birth! It was suggested, writes Gordlevsky, that such a joker as Nasreddin, and the tombstone inscription should not be read like people, but backwards: 683 AH (1284/85)! In general, somewhere in these centuries our hero was lost.

Researcher K.S. Davletov attributes the birth of the image of Nasreddin to the 8th-11th centuries, the era of the Arab conquests and the struggle of peoples against the Arab yoke: “If you look for a period in the history of the East that could serve as the cradle of the image of Nasreddin Hodja, which could give rise to such a magnificent artistic generalization, then, of course, , we can stop only at this epoch.

It is difficult to agree with the categorical nature of such a statement; the image of Nasreddin, as he came down to us, took shape over the centuries. Among other things, K.S. Davletov refers to “vague” information that “during the time of Caliph Harun ar-Rashid, there lived a famous scientist Mohammed Nasreddin, whose teaching turned out to be contrary to religion. He was sentenced to death and, in order to save himself, pretended to be insane. Under this mask, he then began to ridicule his enemies.

Turkish history professor Mikayil Bayram conducted an extensive study, the results of which showed that the full name of the real prototype of Nasreddin is Nasir ud-din Mahmud al-Khoyi, he was born in the city of Khoy, Iranian province of Western Azerbaijan, was educated in Khorasan and became a student of the famous Islamic figure Fakhr ad-din ar-Razi. The Caliph of Baghdad sent him to Anatolia to organize resistance to the Mongol invasion. He served as a qadi, an Islamic judge, in Kayseri and later became a vizier at the court of Sultan Kay-Kavus II in Konya. He managed to visit a huge number of cities, got acquainted with many cultures and was famous for his wit, so it is quite possible that he was the first hero of funny or instructive stories about Khoja Nasreddin.

True, it seems doubtful that this educated and influential man rode around on a modest donkey and quarreled with his quarrelsome and ugly wife. But what a noble cannot afford is quite accessible to the hero of funny and instructive anecdotes, isn't it?

However, there are other studies that admit that the image of Khoja Nasreddin is a good five centuries older than is commonly believed in modern science.

Academician V.A. Gordlevsky believed that the image of Nasreddin came out of the anecdotes created among the Arabs around the name of Juhi, and passed to the Seljuks, and later to the Turks as its extension.

An interesting hypothesis was put forward by Azerbaijani scientists. A number of comparisons allowed them to assume that the famous Azerbaijani scientist Haji Nasireddin Tusi, who lived in the 13th century, was the prototype of Nasreddin. Among the arguments in favor of this hypothesis is, for example, the fact that in one of the sources Nasreddin is called by this name - Nasireddin Tusi.

In Azerbaijan, Nasreddin's name is Molla - perhaps this name, according to researchers, is a distorted form of the name Movlan, which belonged to Tusi. He had another name - Hassan. This point of view is confirmed by the coincidence of some motifs from the works of Tusi himself and anecdotes about Nasreddin (for example, ridicule of soothsayers and astrologers). The considerations are interesting and not without persuasiveness.

Thus, if you start looking in the past for a person similar to Nasreddin, it will very soon become clear that his historicity borders on legendary. However, many researchers believe that the traces of Khoja Nasreddin should be sought not in historical chronicles and grave crypts, which, judging by his character, he did not want to get into, but in those parables and anecdotes that twenty-three peoples told and still tell the Middle East and Central Asia, and not only them.

Folk tradition draws Nasreddin truly many-sided. Sometimes he appears as an ugly, unsightly man in an old, worn dressing gown, in the pockets of which, alas, there are too many holes for something to be stale. Why, sometimes his dressing gown is simply greasy with dirt: long wanderings and poverty take their toll. At another time, on the contrary, we see a person with a pleasant appearance, not rich, but living in abundance. In his house there is a place for holidays, but there are also black days. And then Nasreddin sincerely rejoices at the thieves in his house, because finding something in empty chests is real luck.

Khoja travels a lot, but it is not clear where is his home after all: in Akshehir, Samarkand, Bukhara or Baghdad? Uzbekistan, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Armenia (yes, she too!), Greece, Bulgaria are ready to give him shelter. His name is declined in different languages: Khoja Nasreddin, Jokha Nasr-et-din, Mulla, Molla (Azerbaijani), Afandi (Uzbek), Ependi (Turkmen), Nasyr (Kazakh), Anasratin (Greek). Friends and students are waiting for him everywhere, but there are also enough enemies and ill-wishers.

The name Nasreddin is spelled differently in many languages, but they all derive from the Arabic Muslim personal name Nasr ad-Din, which translates as "Victory of the Faith." Nasreddin is addressed in different ways in the parables of different peoples - it can be the respectful address “Khoja”, and “Molla”, and even the Turkish “efendi”.

It is characteristic that these three appeals - Khoja, Molla and Efendi - are in many respects very close concepts. Compare yourself. “Khoja” in Farsi means “master”. This word exists in almost all Turkic languages, as well as in Arabic. Initially, it was used as the name of the clan of the descendants of Islamic Sufi missionaries in Central Asia, representatives of the “white bone” estate (Turk. “ak suyuk”). Over time, “Khoja” became an honorary title, in particular, Islamic spiritual mentors of Ottoman princes or teachers of Arabic literacy in a mekteb, as well as noble husbands, merchants or eunuchs in ruling families, began to be called this way.

Mulla (molla) has several meanings. For Shiites, a mullah is the leader of a religious community, a theologian, an expert in interpreting issues of faith and law (for Sunnis, these functions are performed by the ulema). In the rest of the Islamic world, in a more general sense, as a respectful title, it can mean: “teacher”, “assistant”, “owner”, “protector”.

Efendi (afandi, ependi) (this word has Arabic, Persian, and even ancient Greek roots) means "one who can (in court) defend himself"). This is an honorary title of noble people, a polite treatment with the meanings of "master", "respected", "master". Usually followed the name and was given mainly to representatives of scientific professions.

But back to the reconstructed biography. Khoja has a wife, son and two daughters. The wife is a faithful interlocutor and eternal opponent. She is grumpy, but sometimes much wiser and calmer than her husband. His son is completely different from his father, and sometimes he is just as cunning and troublemaker.

Khoja has many professions: he is a farmer, a merchant, a doctor, a healer, he even trades in theft (most often unsuccessfully). He is a very religious person, so his fellow villagers listen to his sermons; he is fair and knows the law well, therefore he becomes a judge; he is majestic and wise - and now the great emir and even Tamerlane himself want to see him as his closest adviser. In other stories, Nasreddin is a stupid, narrow-minded person with many shortcomings and is even sometimes reputed to be an atheist.

One gets the impression that Nasreddin is a manifestation of human life in all its diversity, and everyone can (if he wants) discover his own Nasreddin. It is more than enough for everyone, and even left! If Hodge had lived in our time, he probably would have driven a Mercedes, worked part-time at a construction site, begged in subway passages ... and all this at the same time!

It can be concluded that Khoja Nasreddin is, as it were, a different outlook on life, and if certain circumstances cannot be avoided, no matter how hard you try, then you can always learn something from them, become a little wiser, and therefore much freer from these very circumstances! And maybe, at the same time, it will turn out to teach someone else ... or teach a lesson. Well, since life itself has taught nothing! Nasreddin will definitely not rust, even if the devil himself is in front of him.

For the Arab tradition, Nasreddin is not an accidental character. It is not at all a secret that every fable or anecdote about him is a storehouse of ancient wisdom, knowledge about the path of a person, about his destiny and ways of gaining a true existence. And Hoxha is not just an eccentric or an idiot, but someone who, with the help of irony and paradox, tries to convey high religious and ethical truths. It can be boldly concluded that Nasreddin is a real Sufi!

Sufism is an internal mystical trend in Islam that developed along with official religious schools. However, the Sufis themselves say that this trend is not limited to the religion of the prophet, but is the seed of any genuine religious or philosophical teaching. Sufism is the striving for Truth, for the spiritual transformation of man; this is a different way of thinking, a different view of things, free from fears, stereotypes and dogmas. And in this sense, real Sufis can be found not only in the East, but also in Western culture.

The mystery that Sufism is shrouded in, according to its followers, is connected not with some special mysticism and secrecy of the teaching, but with the fact that there were not so many sincere and honest seekers of truth in all ages. “To be in the world, but not of the world, to be free from ambition, greed, intellectual arrogance, blind obedience to custom or reverent fear of superiors - this is the ideal of the Sufi,” wrote Robert Graves, an English poet and scholar.

In our age, accustomed to sensations and revelations, these truths pale before stories of mystical miracles and world conspiracies, but it is about them that the sages speak. And with them Nasreddin. The truth is not far away, it is here, hidden behind our habits and attachments, behind our selfishness and stupidity. The image of Khoja Nasreddin, according to Idris Shah, is an amazing discovery of the Sufis. Khoja does not teach or rant, there is nothing far-fetched in his tricks. Someone will laugh at them, and someone, thanks to them, will learn something and realize something. Stories live their lives, wandering from one nation to another, Hodge travels from anecdote to anecdote, the legend does not die, wisdom lives on. Indeed, it was hard to find a better way to convey it!

Khoja Nasreddin constantly reminds us that we are limited in understanding the essence of things, and therefore in their assessment. And if someone is called a fool, there is no point in being offended, because for Khoja Nasreddin such an accusation would be the highest of praises! Nasreddin is the greatest teacher, his wisdom has long crossed the borders of the Sufi community. But few people know this Hodja. In the East, there is a legend that says that if you tell seven stories about Khoja Nasreddin in a special sequence, then a person will be touched by the light of eternal truth, giving extraordinary wisdom and power. How many were those who from century to century studied the legacy of the great mockingbird, one can only guess. A lifetime can be spent in search of this magical combination, and who knows if this legend is not another joke of the incomparable Hoxha?

Generations changed generations, fairy tales and anecdotes were passed from mouth to mouth throughout all the tea and caravanserai of Asia, the inexhaustible folk fantasy added to the collection of stories about Khoja Nasreddin all new parables and anecdotes that spread over a vast territory. The themes of these stories have become part of the folklore heritage of several peoples, and the differences between them are explained by the diversity of national cultures. Most of them depict Nasreddin as a poor villager and have absolutely no reference to the time of the story - their hero could live and act in any time and era.

For the first time, the stories about Khoja Nasreddin were subjected to literary processing in 1480 in Turkey, being recorded in a book called "Saltukname", and a little later, in the 16th century, by the writer and poet Jami Ruma Lamiya (died in 1531), the following manuscript with stories about Nasreddin dates back to 1571. Later, several novels and stories about Khoja Nasreddin were written (Nasreddin and his wife by P. Millin, Rosary from cherry stones by Gafur Gulyam, etc.).

Well, the 20th century brought the stories about Khoja Nasreddin to the movie screen and the theater stage. Today, the stories about Khoja Nasreddin have been translated into many languages and have long become part of the world's literary heritage. Thus, 1996-1997 was declared by UNESCO the International Year of Khoja Nasreddin.

The main feature of the literary hero Nasreddin is to get out of any situation as a winner with the help of a word. Nasreddin, masterfully mastering the word, neutralizes any of his defeats. Hoxha's frequent tricks are feigned ignorance and the logic of the absurd.

The Russian-speaking reader knows the stories about Khoja Nasreddin not only from collections of parables and anecdotes, but also from the wonderful novels by Leonid Solovyov "Troublemaker" and "The Enchanted Prince", combined into "The Tale of Khoja Nasreddin", also translated into dozens of foreign languages.

In Russia, the “official” appearance of Khoja Nasreddin is associated with the publication of the “History of Turkey” by Dmitry Cantemir (Moldovan ruler who fled to Peter I), which included the first historical anecdotes about Nasreddin (Europe met him much earlier).

The subsequent, unofficial existence of the great Hoxha is shrouded in mist. Judge for yourself. Once, leafing through a collection of fairy tales and fables collected by folklorists in Smolensk, Moscow, Kaluga, Kostroma and other regions in the 60-80s of the last century, researcher Alexei Sukharev found several anecdotes that exactly repeat the stories of Khoja Nasreddin. Judge for yourself. Foma says to Yerema: “My head hurts, what should I do?”. Yerema replies: "When I had a toothache, I pulled it out."

And here is Nasreddin's version. “Afandi, what should I do, my eye hurts?” a friend asked Nasreddin. “When I had a toothache, I couldn’t calm down until I pulled it out. Probably, you need to do the same, and you will get rid of the pain, ”advised Hoxha.

It turns out that this is nothing unusual. Such jokes can be found, for example, in the German and Flemish legends about Thiel Ulenspiegel, in Boccaccio's Decameron, and in Cervantes' Don Quixote. Similar characters among other peoples: Sly Peter - among the southern Slavs; in Bulgaria there are stories in which two characters are simultaneously present, competing with each other (most often - Khoja Nasreddin and Sly Peter, which is associated with the Turkish yoke in Bulgaria).

The Arabs have a very similar character Jokha, the Armenians have Pulu-Pugi, the Kazakhs (along with Nasreddin himself) have Aldar Kose, the Karakalpaks have Omirbek, the Crimean Tatars have Akhmet-akai, the Tajiks have Mushfiks, the Uighurs have Salai Chakkan and Molla Zaydin, Turkmens - Kemine, Ashkenazi Jews - Hershele Ostropoler (Hershele from Ostropol), Romanians - Pekale, Azerbaijanis - Molla Nasreddin. In Azerbaijan, the satirical magazine Molla Nasreddin, published by Jalil Mammadguluzade, was named after Nasreddin.

Of course, it is difficult to say that the stories about Khoja Nasreddin influenced the appearance of similar stories in other cultures. Somewhere for researchers this is obvious, but somewhere it is not possible to find visible connections. But it is difficult not to agree that there is something unusually important and attractive in this. Knowing nothing about Nasreddin, we also know nothing about ourselves, about those depths that are reborn in us, whether we live in Samarkand of the XIV century or in a modern European city. Truly, the boundless wisdom of Khoja Nasreddin will outlive all of us, and our children will laugh at his tricks just as our grandfathers and great-grandfathers once laughed at them. Or maybe they won’t… As they say in the East, everything is the will of Allah!

Of course, there will definitely be someone who will say that Nasreddin is incomprehensible or simply outdated. Well, if Hodge happened to be our contemporary, he would not be upset: you can’t please everyone. Yes, Nasreddin did not like to get upset at all. The mood is like a cloud: it ran and flew away. We get upset only because we lose what we had. But it is worth considering: do we really have so much? There is something wrong when a person determines his dignity by the amount of accumulated property. After all, there is something that you can’t buy in a store: intelligence, kindness, justice, friendship, resourcefulness, wisdom, finally. Now, if you lost them, then there is something to be upset about. As for the rest, Khoja Nasreddin has nothing to lose, and this, perhaps, is his most important lesson.

So what, after all, in the end? At the moment, there is no confirmed information or serious grounds to talk about the specific date or place of Nasreddin's birth, so the question of the reality of the existence of this character remains open. In a word, whether Khoja was born or not born, lived or did not live, died or did not die, is not very clear. A complete misunderstanding and misunderstanding. Don't laugh or cry, just shrug. Only one thing is known for certain: many wise and instructive stories about Khoja Nasreddin have come down to us. Therefore, in conclusion, a few of the most famous.

Once at the bazaar, Khoja saw a fat teahouse owner shaking a beggar tramp, demanding payment for lunch from him.

- But I just sniffed your pilaf! - justified the tramp.

- But the smell also costs money! - answered the fat man.

- Wait, let him go - I'll pay you for everything - with these words Khoja Nasreddin went up to the teahouse owner. He released the poor man. Khoja took out a few coins from his pocket and shook them over the ear of the teahouse keeper.

- What is this? - he was amazed.

“Whoever sells the smell of dinner gets the sound of coins,” Hodge replied calmly.

The following story, one of the most beloved, is given in the book by L.V. Solovyov "Troublemaker" and in the film "Nasreddin in Bukhara" based on the book.

Nasreddin says that he once argued with the emir of Bukhara that he would teach his donkey theology so that the donkey would know him no worse than the emir himself. This requires a purse of gold and twenty years of time. If he does not fulfill the conditions of the dispute - the head off his shoulders. Nasreddin is not afraid of the inevitable execution: “After all, in twenty years,” he says, “either the shah dies, or I, or the donkey dies. And then go and figure out who knew theology better!”

An anecdote about Khoja Nasreddin is given even by Leo Tolstoy.

Nasreddin promises a merchant for a small fee to make him fabulously rich through magic and sorcery. To do this, the merchant had only to sit in a bag from dawn to dusk without food or drink, but the main thing: during all this time he should never think about a monkey, otherwise everything will be in vain. It is not difficult to guess whether the merchant became fabulously rich ...

The article uses materials from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (article "Khodja Nasreddin"), from the book "Good Jokes of Khoja Nasreddin" by Alexei Sukharev, from the book "Twenty-four Nasreddin" (Compiled by M.S. Kharitonov)

Leonid Solovyov: The Tale of Hodja Nasreddin:

TROUBLESHOOTER

CHAPTER FIRST

Khoja Nasreddin met the thirty-fifth year of his life on the road.

He spent more than ten years in exile, wandering from city to city, from one country to another, crossing seas and deserts, spending the night as he had to - on bare ground near a meager shepherd's fire, or in a cramped caravanserai, where in dusty darkness until morning camels sigh and itch and tinkle dully with bells, or in a fumed, smoky teahouse, among the water carriers lying side by side, beggars, drovers and other poor people, who, with the onset of dawn, fill the market squares and narrow streets of cities with their piercing cries. Often he managed to spend the night on soft silk pillows in the harem of some Iranian nobleman, who just that night went with a detachment of guards to all the teahouses and caravanserais, looking for the tramp and blasphemer Khoja Nasreddin in order to put him on a stake ... Through the bars through the window one could see a narrow strip of sky, the stars were growing pale, the pre-dawn breeze rustled lightly and gently through the foliage, on the windowsill merry doves began to coo and clean their feathers. And Khoja Nasreddin, kissing the weary beauty, said:

It's time. Farewell, my incomparable pearl, and do not forget me.

Wait! - she answered, closing her beautiful hands on his neck. - Are you leaving completely? But why? Listen, tonight, when it gets dark, I'll send the old woman for you again. - No. I have long forgotten the time when I spent two nights in a row under the same roof. I have to go, I'm in a hurry.

Drive? Do you have any urgent business in another city? Where are you going to go?

Don't know. But it is already dawn, the city gates have already opened and the first caravans have set off. Can you hear the camel bells ringing! When I hear this sound, it's like genies are infused in my legs, and I can't sit still!

Leave if so! the beauty said angrily, trying in vain to hide the tears glistening on her long eyelashes. - But tell me at least your name in parting.

Do you want to know my name? Listen, you spent the night with Khoja Nasreddin! I am Khoja Nasreddin, a disturber of the peace and a sower of discord, the very one about whom heralds shout every day in all squares and bazaars, promising a big reward for his head. Yesterday they promised three thousand fogs, and I even thought about selling my own head myself for such a good price. You laugh, my little star, well, give me your lips for the last time. If I could, I would give you an emerald, but I don’t have an emerald - take this simple white pebble as a keepsake!

He pulled on his tattered dressing gown, burned in many places by the sparks of road fires, and moved away slowly. Behind the door, a lazy, stupid eunuch in a turban and soft shoes with upturned toes snored loudly - a negligent guardian of the main treasure in the palace entrusted to him. Farther on, stretched out on carpets and felt mats, the guards snored, resting their heads on their naked scimitars. Khoja Nasreddin would tiptoe past, and always safely, as if becoming invisible for the time being.

And again the white stony road rang, smoked under the brisk hooves of his donkey. Above the world in the blue sky the sun shone; Khoja Nasreddin could look at him without squinting. Dewy fields and barren deserts, where camel bones half covered with sand, green gardens and foamy rivers, gloomy mountains and green pastures, heard the song of Khoja Nasreddin. He drove farther and farther away, not looking back, not regretting what he had left behind, and not fearing what lies ahead.

And in the abandoned city, the memory of him forever remained to live.

The nobles and mullahs turned pale with rage, hearing his name; water carriers, drovers, weavers, coppersmiths and saddlers, gathering in the evenings in teahouses, told each other funny stories about his adventures, from which he always emerged victorious; the languid beauty in the harem often looked at the white pebble and hid it in a mother-of-pearl chest, hearing the steps of her master.

Phew! - said the fat nobleman and, puffing and sniffing, began to pull off his brocade robe. - We are all completely exhausted with this accursed vagabond Khoja Nasreddin: he angered and stirred up the whole state! Today I received a letter from my old friend, the respected ruler of the Khorasan district. Just think - as soon as this vagabond Khoja Nasreddin appeared in his city, the blacksmiths immediately stopped paying taxes, and the keepers of the taverns refused to feed the guards for free. Moreover, this thief, the defiler of Islam and the son of sin, dared to climb into the harem of the Khorasan ruler and dishonor his beloved wife! Truly, the world has never seen such a criminal! I regret that this despicable ragamuffin did not try to enter my harem, otherwise his head would have stuck out on a pole in the middle of the main square a long time ago!

The beauty was silent, secretly smiling - she was both funny and sad. And the road kept ringing, smoking under the hooves of the donkey. And the song of Khoja Nasreddin sounded. For ten years he traveled everywhere: in Baghdad, Istanbul and Tehran, in Bakhchisaray, Etchmiadzin and Tbilisi, in Damascus and Trebizond, he knew all these cities and a great many others, and everywhere he left a memory of himself.

Now he was returning to his native city, to Bukhara-i-Sherif, to Noble Bukhara, where he hoped, hiding under a false name, to take a break from endless wanderings.

CHAPTER TWO

Having joined a large merchant caravan, Khoja Nasreddin crossed the Bukhara border and on the eighth day of the journey he saw the familiar minarets of the great, glorious city in the distance in a dusty haze.

The caravaners, exhausted by thirst and heat, shouted hoarsely, the camels quickened their pace: the sun was already setting, and it was necessary to hurry to enter Bukhara before the city gates were closed. Khoja Forward din rode at the very tail of the caravan, shrouded in a thick, heavy cloud of dust; it was native, sacred dust; it seemed to him that it smelled better than the dust of other distant lands. Sneezing and clearing his throat, he said to his donkey:

Well, we are finally home. I swear by Allah, good luck and happiness await us here.

The caravan approached the city wall just as the guards were locking the gates. "Wait, in the name of Allah!" shouted the caravan-bashi, showing a gold coin from afar. But the gates were already closed, the bolts fell with a clang, and sentries stood on the towers near the cannons. A cool wind blew, the pink glow faded in the foggy sky and the thin crescent of the new moon clearly appeared, and in the twilight silence from all the countless minarets the high, drawn-out and sad voices of the muezzins called Muslims to evening prayers.

The merchants and caravaners knelt down, and Khoja Nasreddin with his donkey moved slowly aside.

These merchants have something to thank Allah for: they had lunch today and are now going to have dinner. And you and I, my faithful donkey, have not had lunch and will not have dinner; if Allah wants to receive our gratitude, then let him send me a bowl of pilaf, and you - a sheaf of clover!

He tied the donkey to a roadside tree, and he himself lay down beside him, right on the ground, putting a stone under his head. Shining plexuses of stars were opened to his eyes in the dark transparent sky, and each constellation was familiar to him: so often in ten years he had seen the open sky above him! And he always thought that these hours of silent wise contemplation make him richer than the richest, and although the rich man eats on golden dishes, he must certainly spend the night under a roof, and it is not given to him at midnight, when everything calms down, to feel the flight of the earth through blue and cool star mist...

Meanwhile, in the caravanserais and teahouses adjoining the battlements of the city outside, fires lit up under large cauldrons and rams bleated plaintively, which were dragged to the slaughter. But the experienced Khoja Nasreddin prudently settled down for the night on the windward side, so that the smell of food would not tease or disturb him. Knowing the Bukhara order, he decided to save the last money in order to pay a fee at the city gates in the morning.

He tossed and turned for a long time, but sleep did not come to him, and hunger was not at all the cause of insomnia. Khoja Nasreddin was tormented and tormented by bitter thoughts; even the starry sky could not console him today.

He loved his homeland, and there was no greater love in the world for this cunning merry fellow with a black beard on a copper-tanned face and crafty sparks in his clear eyes. The farther from Bukhara he wandered in a patched robe, greasy skullcap and torn boots, the more he loved Bukhara and yearned for her. In his exile, he always remembered the narrow streets, where the cart, passing, harrowed clay fences on both sides; he remembered the tall minarets with patterned tiled hats, on which the fiery brilliance of dawn burns in the morning and evening, the ancient, sacred elms with huge nests of storks blackening on the branches; he remembered the smoky teahouses above the ditches, in the shade of murmuring poplars, the smoke and fumes of taverns, the motley hustle and bustle of the bazaars; he remembered the mountains and rivers of his homeland, its villages, fields, pastures and deserts, and when in Baghdad or Damascus he met a compatriot and recognized him by the pattern on his skullcap and by the special cut of his robe, Khoja Nasreddin's heart sank and his breath became shy.

When he returned, he saw his homeland even more unhappy than in the days when he left it. The old emir was buried long ago. The new emir managed to completely ruin Bukhara in eight years. Khoja Nasreddin saw destroyed bridges on the roads, poor crops of barley and wheat, dry ditches, the bottom of which was cracked from the heat. The fields grew wild, overgrown with weeds and thorns, orchards were dying of thirst, the peasants had neither bread nor cattle, the beggars sat in strings along the roads, begging for alms from the same beggars as themselves. The new emir placed detachments of guards in all the villages and ordered the inhabitants to feed them free of charge, founded many new mosques and ordered the inhabitants to finish building them - he was very pious, the new emir, and twice a year he always went to worship the ashes of the most holy and incomparable Sheikh Bogaeddin, the tomb which rose near Bukhara. In addition to the previous four taxes, he introduced three more, set a fare across each bridge, increased trade and judicial duties, minted counterfeit money ... Crafts fell into decay, trade was destroyed: Khoja Nasreddin was sadly met by his beloved homeland.

... Early in the morning, muezzins again sang from all the minarets; the gates opened, and the caravan, accompanied by the dull ringing of sleigh bells, slowly entered the city.

Outside the gate the caravan stopped: the road was blocked by guards. There were a great many of them - shod and barefoot, dressed and half-naked, who had not yet managed to get rich in the Emir's service. They pushed, shouted, argued, distributing the profit among themselves in advance. Finally, the toll collector came out of the tea house - fat and sleepy, in a silk dressing gown with greasy sleeves, shoes on his bare feet, with traces of intemperance and vice on his swollen face. Casting a greedy glance on the merchants, he said:

Greetings, merchants, I wish you good luck in your business. And know that there is an order from the emir to beat with sticks to death anyone who hides even the smallest amount of goods!

The merchants, seized with embarrassment and fear, silently stroked their dyed beards. The Collector turned to the guards, who had long been dancing in place with impatience, and wiggled his thick fingers. It was a sign. The guards with a boom and a howl rushed to the camels. In a crush and haste, they cut hair lassos with sabers, ripped bales loudly, threw brocade, silk, velvet, boxes of pepper, tea and amber, jugs with precious rose oil and Tibetan medicines onto the road.

From horror, the merchants lost their language. Two minutes later, the inspection ended. The guards lined up behind their leader. Their robes were bristling and puffy. The collection of duties for goods and for entry into the city began. Khoja Nasreddin had no goods; he was charged a duty only for entry.

Where did you come from and why? asked the assembler. The scribe dipped a quill pen into the inkwell and prepared to write down Khoja Nasreddin's answer.