How the prophetic Oleg is now going

Take revenge on the unreasonable Khazars...

A. S. Pushkin

The Khazars, which the great Russian poet mentions in The Song of the Prophetic Oleg, is another mystery of history. It is known that the prince of Kyiv had good enough reasons for revenge: at the beginning of the 10th century, the Khazars defeated and imposed tribute on many Slavic tribes. The Khazars lived east of the Slavs. The Byzantines write about Khazaria as a state allied to them (even the henchman of the kagan, i.e. the king, Leo Khazar, sat on the throne in Constantinople): "Ships come to us and bring fish and skin, all kinds of goods ... they are with us in friendship and we eat ... possess military force and power, hordes and troops". Chroniclers speak of the greatness of the capital Itil. Surrounded by large settlements, castles that stood on trade routes grew into cities. Itil was such a city that grew out of the kagan's castle, which, as we know from sources, was located somewhere in the delta of the Volga. Many attempts to find its ruins for a long time did not lead to anything. It seems to have been completely washed away by the frequently changing course of the river. Several fairly detailed, although sometimes contradictory, ancient descriptions of this city have come down to us (mostly Arab authors). Itil consisted of two parts: a brick palace-castle built on an island, connected to the castle by floating bridges and also fenced with a powerful wall made of mud bricks. The fortress of the kagan was called al-Bayda, or Sarashen, which meant "white fortress". It had many public buildings: baths, bazaars, synagogues, churches, mosques, minarets and even madrasahs. Randomly scattered private buildings were adobe houses and yurts. Merchants, artisans and various common people lived in them.

Khazars - in Arabic Khazar - the name of the people of Turkic origin. This name comes from the Turkish qazmak (to wander, move) or from quz (country of the mountain turned to the north, shady side). The name "Khazars" was known even to the first Russian chronicler, but no one really knew who they were and where the "core" of Khazaria was, no archaeological monuments remained of it. Lev Nikolaevich Gumilyov spent more than one year studying this issue. In the late 50s - early 60s, he repeatedly traveled to the Astrakhan region as the head of the archaeological expedition of the Russian Academy of Sciences, wrote in his writings that the Khazars had two major cities: Itil on the Volga and Semender on the Terek. But where are their ruins? The Khazars were dying - where did their graves go?

The historically educated reader knows that the Khazars were a powerful people who lived in the lower reaches of the Volga, professed the Jewish faith and in 965 were defeated by the Kyiv prince Svyatoslav Igorevich. The reader - historian or archaeologist - poses many questions: what was the origin of the Khazars, what language did they speak, why did their descendants not survive, how could they profess Judaism when it was a religion, conversion to which was forbidden by its own canons, and, most importantly, how did the Khazar people themselves, the country inhabited by them, and the huge Khazar kingdom, which covered almost the entire South-Eastern Europe and was inhabited by many peoples, correlate with each other?

L.N. Gumilyov. Discovery of Khazaria.

Found the legendary city of Itil...

And now archaeologists announced that they managed to make a long-awaited discovery: to discover the capital of the ancient Khazar Khaganate - the legendary city of Itil ... This was announced by one of the leaders of the expedition of the Russian Academy of Sciences, candidate of historical sciences Dmitry Vasiliev.

According to the scientist, a joint expedition of archaeologists from the Astrakhan State University and the Institute of Ethnology of the Russian Academy of Sciences worked on the Samosdelsky settlement near the village of Samosdelki, Kamyzyaksky district of the Astrakhan region. The researchers came to the conclusion that this settlement is the ancient capital of Khazaria.

"Our scientific team, we are now publicly declaring this at scientific conferences says the archaeologist. - We found a very powerful cultural layer.

There are about three and a half meters, and not only the Khazar time, but also the pre-Mongolian and Golden Horde times. A large number of brick buildings were found, the contours of the citadel, the island on which the central part of the city stood, and less prosperous quarters were revealed.

According to him, archaeologists have been working on the settlement for ten years already - since 2000, a large number of interesting finds have been made there. "We donate them to our Astrakhan museum, every year 500-600 items. This is the 8th-10th centuries of our era," Vasiliev added.

However, it will never be possible to prove "100%" that the found city is Itil, the scientist believes. "There are always some doubts - after all, we will not be able to find a sign with the inscription "City of Itil".

There are a lot of indirect signs on which we are based," he explains. Firstly, archaeologists pay attention to the presence of a brick fortress: "Brick construction in Khazaria was a royal monopoly, and we know only one brick fortress on the territory of the Khazar Khaganate.

This is Sarkel, which was built directly by the royal decree. "Secondly, using the radiocarbon method, the lower layers of the Samosdelsky settlement were dated to the VIII-IX centuries - that is, the Khazar time.

The large size of the city also speaks in favor of the hypothesis of archaeologists. "Investigated, or rather explored, famous area- more than two square kilometers, according to the Middle Ages - this is a giant city. We do not know the density of the population, but we can assume that its population was 50-60 thousand people," Vasiliev said.

He added that the last mention of the Khazars dates back to the 12th century, after which they disappeared into the mass of other peoples and lost their ethnic identity. However, Itil continued to exist in the Golden Horde era and disappeared in the XIV century due to the rise in the level of the Caspian, it was simply flooded.

Astrakhan archaeologists are sure they have found the legendary Itil

A joint expedition of archaeologists from the Astrakhan State University and the Institute of Ethnology of the Russian Academy of Sciences at the Samosdelskoye settlement near the village of Sasmadeki, Kamyzyaksky district of the Astrakhan region, found confirmation that the settlement, on which excavations scientists have been working for more than one year, is the legendary Itil.

Employees of the archaeological laboratory took a panorama of the settlement from the air. It turned out that in ancient times in this now arid place there was an island surrounded on all sides by deep channels. The island was small, and people also settled along the banks of the river. This coincided with medieval descriptions of the city of Itil, which are found among Arab historians and geographers.

Based on materials from the media of the Astrakhan region - AIF

Vladimir Yakovlevich Petrukhin - Doctor of Historical Sciences,

Leading Researcher, Institute of Slavic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences,

professor at RSUH.

When it comes to the Khazars, the first thing that comes to mind is Pushkin's "Song of the Prophetic Oleg", familiar from the school desk:

How the prophetic Oleg is now going

Take revenge on the unreasonable Khazars.

Their villages and fields for a violent raid

He doomed swords and fires ...

The plot of Pushkin's "song" is not at all connected with the Khazars - after all, it tells about the death of Oleg from his beloved horse, but the beginning of any story is always remembered in the first place. At the time of Pushkin, they did not really know who the Khazars were, but they remembered that the beginning of proper Russian history was connected with them.

Nestor the chronicler, who told at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries. about the first Russian princes and the death of Oleg, begins Russian history with a mention of the tribute that the Khazars collected from the Slavic tribes of the Middle Dnieper, and the overseas Varangians from the tribes of Novgorod land back in the middle of the 9th century. Nestor tells in the Primary Chronicle - "The Tale of Bygone Years", how the steppe-Khazars approached the land of the meadows - the inhabitants of Kyiv and demanded tribute from them, and the meadows gave them tribute with swords. The Khazar elders saw in this tribute an unkind sign: after all, the Khazars conquered many lands with sabers sharpened on one side, and the swords were double-edged. And so it happened - Nestor completes his story about the Khazar tribute, the Russian princes began to own the Khazars.

The annals say nothing about revenge on the Khazars by the prophetic Oleg - this is a poetic "reconstruction" of history: in fact, it was "unreasonable" to oppress the Slavs and make "violent raids". The chronicle describes the relationship between Oleg and the Khazars in a different way. Oleg was a Varangian, heir Prince of Novgorod Rurik. He was called from across the sea with his Scandinavian (Varangian) squad, nicknamed Rus, to the Novgorod land to rule there according to Slavic customs - "in a row, by right." An outstanding domestic orientalist A.P. Novoseltsev even believed that the Slavs called the Viking Varangians to Novgorod in order to avoid the Khazar threat. One way or another, the first prince sent to the south - to Tsargrad, along the famous path from the Varangians to the Greeks, his warriors, who settled in Kiev, and after the death of Rurik, Oleg went there with the young Igor Rurikovich. He appeared in Kyiv in the 880s, proclaimed the new capital "the mother of Russian cities" and agreed with the Slavic tribes - tributaries of the Khazars, that they would pay tribute to the Russian prince. It was still far from “revenge” here - the Khazars were already “avenged” by Igor’s heir Svyatoslav, who in the 960s defeated the Khazar state, and only the remains of the Khazar cities - settlements on the Don and Seversky Donets, in the North Caucasus and in the Crimea - remind of once powerful Khazar state.

Archaic mythological plot with the World Tree.

Drawing from a vessel found in a burial ground on the Lower Don.

Publication by S.I. Bezuglov and S.A. Naumenko.

Real history is incomparably richer and more interesting than this old official doctrine. The Khazars were by no means the first inhabitants of the Eurasian steppe who sought to impose tribute on farmers and townspeople. At the end of IV-V century. Europe was shocked by the Hun invasion: the ancient cities of the Northern Black Sea region were destroyed, nomadic hordes rushed to Central Europe, to Rome and Constantinople, the centers of the Roman Empire. But the huge Hunnic state collapsed by the 6th century, and the Huns from Central Asia a new wave of conquerors came - the Turks, who created their own "empire" - the Turkic Khaganate. The title of the lord of this "empire" - kagan, "khan of khans", was equated with the imperial title. Then, in the 6th century, Slavs began to settle from Central Europe to the Danube and to the east - to the Dnieper and Volkhov.

.

The Khazars are first mentioned in a certain historical and geographical context as a people living in the "Hunnic limits" north of the Caspian Gates - Derbent (Bab al-abwab). The very name Khazars most researchers correlate with traditional Turkic ethnonyms such as Kazakh denoting a nomad (it is assumed that Chinese sources called them Ko-sa). Syrian Christian author of the middle of the VI century. Zechariah Rhetor in his "Chronicle" first lists the five Christian peoples of the Caucasus, to which he also refers the Huns, then gives a description of the barbarian nomads. "Anvar, Sebir, Burgar, Alan, Kurtagar, Avars, Khasar, Dirmar, Sirurgur, Bagrasik, Kulas, Abdel, Eftalit - these 13 peoples live in tents, exist on the meat of cattle and fish, wild animals and weapons." The "Hun limits" of Zechariah are given extremely broadly, if he also includes the Central Asian Ephthalites ("White Huns"), but the Khazars, obviously, close the list of nomadic peoples of the Black Sea steppes: Sebirs - Savirs, Burgars - Bulgarians, Alans - Alans, Kurtagars - Kutrigurs, Avars - Avars, Khasar - Khazars.

In the VI century. after the Huns lost their power in the Eurasian steppes, a new state association arose in Central Asia, created by the Turks, headed by their ruler - a kagan from the Ashina clan - the Turkic Khaganate. His possessions stretched from Central Asia to the Black Sea steppes and included big number peoples. Since then, the Turkic peoples have replaced Iranian-speaking nomads in the steppes - Sarmatians, Alans. In the 7th century The Turkic Khaganate broke up into warring groups of Turks. On the western outskirts of the Khaganate, the Turks subjugated the Hephthalites and began to threaten Iran, including in Transcaucasia, which was subject to it - it was not for nothing that the Iranian rulers of the Sassanids began to fortify Derbent in the Caspian so that the Turks would not break into Iran-controlled Armenia through the Caspian gates.

In 626, when the Avars Turks, who migrated to Central Europe in the 6th century, and their allies, the Slavs, besieged Constantinople, the Khazars were already included in the general geopolitical system - the situation of the struggle of two great powers - and acted in Transcaucasia on the side of Byzantium, then Iran. In Armenian sources, the ruler of the Khazars is called jebu hakan and is recognized as the second person in the hierarchy of the ruling layer of the Turkic Khaganate. In the era of the collapse of the Turkic Khaganate, the Bulgarian association of tribes, headed by the noble Dulo family, supported one of the Turkic groups that fought for power in the Khaganate, the Khazars supported the other; It is believed that after the collapse of the Turkic Khaganate in the middle of the 7th century. a “prince” from the Ashina clan fled to them, which gave the rulers of the Khazars the right to be called khagans (khakans).

Khazaria and neighboring regions in10th century

Map from the book: Golb N., Pritsak O.

Khazar-Jewish Documents10th century

Moscow - Jerusalem, 1997.

The nomadic Bulgarians (proto-Bulgarians) in the process of disintegration of the state of the Huns, pressed by other Turkic nomadic Aquarians, in interaction with Iranian and Ugric tribal elements from the second half of the 5th century BC. invaded the Black Sea region. Tribes of Kutrigurs, Utigurs, Saragurs, Onogurs, Ogurs (Urogs, Ogors), Barsils, Savirs, Balanjars in the 5th-7th centuries. inhabited the territory from the Lower Danube to the Eastern Sea of Azov, lived in the North Caucasus, in the Caspian Sea; they fought with the Avar and Turkic Khaganates. In the first third of the 7th c. during the collapse of the Turkic Khaganate, the Onogurs, part of the Kutrigurs and others, led by Khan Kubrat (Kuvrat) from the Dulo clan, formed the association of Great Bulgaria with a center in Phanagoria (on Taman), which included the territory between the Don and Kuban and to the west up to the Middle Dnieper.

Khazar warrior. Drawing by Oleg Fedorov.

The Khazars roamed the fertile lands of the foothills of the North Caucasus - in the country of the Savirs and, no less important, were familiar with the life of ancient cities. Like any nomads, they quickly found profit in the political struggle, which, as always, was waged in the Caucasus by the great powers: in those days it was Byzantium and Iran. In the 7th century the Khazars became so strong that they began to claim dominance not only in the Black Sea steppes, but also in the Byzantine cities of Taman and the Crimea, and in Transcaucasia. A new "empire" was being formed - the Khazar Khaganate: many peoples and lands began to obey the Khagan, the ruler of the Khazars. In the North Caucasus, the Alans, the Iranian-speaking descendants of the ancient Scythians and Sarmatians, became allies and vassals of the Khazars.

In the second half of the 7th c. The Khazars, in alliance with the Alans, who settled in the Caspian steppes and in the North Caucasus, invaded the Sea of \u200b\u200bAzov and defeated Great Bulgaria. After that, part of the Bulgarians, incl. who switched to a settled and semi-settled way of life, remained under the rule of the Khazar Khaganate, making up, along with the Alans, most of the population of Khazaria. Another part of the Bulgarians - a horde led by Khan Asparukh, migrated to the Balkans to Byzantium (681). There, together with the Balkan Slavs, they created a new state - Danube Bulgaria. Another group of Bulgarians retreated to the interfluve of the Volga and Kama: there, by the 9th century. Volga Bulgaria (Bulgaria) was formed, nominally recognizing the power of the Khazar Khagan. In the forest-steppe, the Slavs began to pay tribute to the Khazars, who settled from the Dnieper region to the Oka and Don, including in those regions where farmers did not dare to settle until the time the Cossack villages were created. The power of the Khazars contributed to the Slavic agricultural colonization - after all, the Khazars needed bread and furs obtained in the forests of Eastern Europe.

Having subjugated the Alans, Bulgarians and other peoples of Eastern Europe, the Khazars clashed with Byzantium in its possessions in the Northern Black Sea region. At the end of the 7th-8th centuries. they captured the Bosporus, Eastern Crimea, even claimed Chersonese. But soon the Khazars and Byzantium had a common enemy - the Arab conquerors. The Arabs captured Central Asia, ousted the Khazars from the countries of Transcaucasia, and in 735 invaded the Caspian steppes. The ruler of Khazaria was forced to leave his headquarters in Dagestan - the cities of Belenjer and Semender and found a new capital in the inaccessible Volga delta. It received the same Turkic name as the Volga River: Itil, or Atil. "Jihad" has approached the borders of the current Russian state at the time of the rise of Islam.

The Arabs, however, could not hold out for long in the steppes: they retreated to Transcaucasia, and Derbent remained their outpost - and the outpost of Islam. Kagan restored his power in the North Caucasus and other areas.

This power needed to be strengthened, and the construction of fortifications began in the kaganate. Fortress systems arose in the North Caucasus and on the axial river highway of Khazaria - in the Don basin. For the construction of fortresses, the traditions of both Iranian and Byzantine fortification were used. Around 840, the Byzantine engineer Petrona erected the Sarkel fortress on the Don, excavated in the middle of the 20th century. archaeologists led by the largest researcher of the Khazars - M.I. Artamonov. On the other side of the Don, fortifications were erected that controlled the crossing across the river. A powerful fortress in Khumar controlled the Kuban basin. Settlements of the Khazar time continue to be explored by S.A. Pletneva, M.G. Magomedov, G.E. Afanasiev, V.S. Flerov, V.K. Mikheev, but research has so far affected only an insignificant part of the Khazar heritage.

Fortifications. Hillfort Humara.

The fortress controlled the Kuban basin.

IN last years(since 2000) these fortresses have been studied as part of the Khazar project, initiated by the Russian Jewish Congress (E.Ya. Satanovsky) and the Jewish University in Moscow (now the Higher Humanitarian School named after Sh. Dubnov - coordinators V.Ya. Petrukhin and I.A. Arzhantsev), but archaeologists have to deal primarily with saving dying archaeological sites and fixing the destruction of the Khazar fortresses on the Don, including the Pravoberezhny settlement near the village of Tsimlyanskaya - opposite Sarkel (V.S. Flerov). This white-stone fortress was called together with Sarkel to control the crossing over the Don - the central highway of the Khazar Khaganate. It is interesting that Kyiv, which paid tribute to the Khazars before the appearance of Russian princes there, was located, according to the Russian chronicle, on a ferry across the Dnieper. The Khazars, thus, sought to control the main river communications of Eastern Europe.

Excavations at Samosdelka. Summer 2005. Photo by E. Zilivinskaya.

But the main object of study of the Khazar project was ancient city, discovered in the Volga Delta, on the island of Samosdelka near Astrakhan. There are no such cities in the entire Lower Volga region. The capitals of the Golden Horde - Sarai-Batu and Sarai-Berke, built here by craftsmen brought by the Mongols from Central Asia, did not exist for long - their cultural layer on the main area does not exceed 0.5 m. time - VIII-X centuries. So far, a small area has been excavated (the leaders of the excavations are E.D. Zilivinskaya and D.V. Vasilyev), but it is already clear that brick was used in the construction of buildings (the kagan himself had the right to build bricks in Khazaria), and mass finds indicate that that the population of the city was Bulgarian and Oghuz - from Central Asia. Such was the population of the city in the Volga delta, mentioned by medieval sources - in the pre-Mongolian period it was called Saksin, in the Khazar period - Itil. Itil - the capital of Khazaria, was located in the delta on the island, and perhaps its remains were finally discovered by archaeologists.

Copper belt tips depicting a leopard chasing a hare and a dragon.

XI-13th century Settlement Samosdelka. Excavations by E.D. Zilivinskaya.

Published for the first time.

With the advent of years, the economy of the Khazars became multiform and depended on the traditions of the peoples that were part of the Khaganate. The Alans, who settled not only in the North Caucasus, but also in the Don and Donets basins, were experienced farmers and knew how to build stone fortresses. Agriculture was also practiced by the Khazars, who also learned gardening, winemaking and fishing. The Khazars were residents of ancient cities - Phanagoria and Tamatarkha (Tmutarakan) on Taman, Kerch in the Crimea. The Bulgarians in the steppe preserved mainly a nomadic way of life.

Archaeological monuments of Khazaria are vivid evidence of the formation of urban civilization where previously only steppes stretched and ancient burial mounds rose. But these monuments, like any archeological monuments, are “mute”: the Khazar chronicles have not been preserved, the inscriptions made in Turkic runes are few and have not yet been deciphered. What was said about the Khazar history is known from external - foreign evidence: a treatise by the Byzantine emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, descriptions of the Arab geographer al-Masudi and other Eastern authors.

A defensive system and an economy, even a prosperous one, were not enough to win recognition in the world, even in the early medieval period. And recognition, especially of the great powers, was necessary. During the war with the Muslim Arabs, the kagan faced a confessional problem directly. The Khazars were pagans, they worshiped the Turkic gods, and peaceful relations with the pagans were impossible both from the point of view of orthodox Islam and from the standpoint of Christianity, the state religion of Byzantium.

It is not clear how long and seriously the Khagan professed Islam imposed on him by the Arabs. History has preserved amazing written evidence about the religion of Khazaria, which was brought to us by the so-called Jewish-Khazar correspondence - several letters written in Jewish letters in the 60s. 10th century

Cordova.

The initiator of the correspondence was the dignitary (“chancellor”) of the powerful caliph of Cordoba, the Jewish scholar Hasdai ibn Shaprut. He learned from the merchants that somewhere on the edge of the inhabited world (and North Caucasus was considered in the Middle Ages as the edge of the ecumene) there is a kingdom whose ruler is a Jew. He wrote him a letter asking him to tell about his kingdom. Hasdai was answered by Tsar Joseph, the ruler of Khazaria. He spoke about the enormous size of his state, about the peoples that are subject to it, and finally about how the Khazars became Jews by faith. A distant ancestor of Joseph, who still bore the Turkic name Bulan, saw in a dream an angel of God, who called him to accept the true faith. The angel gave him victory over his enemies - this was an important demonstration of the power of the biblical God for the Khazars, and Bulan and his people converted to Judaism. Then ambassadors from Muslims and from Christian Byzantium came to the king to reason with him: after all, Bulan accepted the faith of a persecuted people everywhere. The king arranged a dispute between Muslims and Christians. He asked the Islamic qadi which faith he considered more true - Judaism or Christianity, and the qadi, who revered the Old Testament prophets, of course, named Judaism. Bulan asked the priest the same question about Judaism and Islam, and he replied that religion old testament more true. So Bulan established himself as the correctness of his choice.

It still remains a mystery when and where the events described in Joseph's letter took place. Therefore, of particular interest are studies within the framework of the Khazar project of new Jewish monuments on Taman, the time of the appearance of which precedes the formation of the Khaganate (S.V. Kashaev, N.V. Kashovskaya).

The letter of the Khazar king was known in the Jewish communities of Spain and was quoted as early as at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries. Entire correspondence was opened for science as early as the 16th century. Isaac Akrish, a descendant of Jews expelled from Spain in 1492, and published it in Constantinople around 1577. European science got acquainted with the correspondence in the second half of the 17th century, but it did not inspire confidence among researchers either in the 18th or even in the 19th century . indeed, in the Renaissance and subsequent centuries - in the period of formation historical science- a lot of hoaxes were created (the writers of “new stories”, such as Academician Fomenko and others like him, are still speculating on this). Moreover, a learned Jew could be suspected of a hoax, who was looking for periods of glory and power in the history of the persecuted people, it was not for nothing that he called the book itself with the publication of correspondence “The Voice of the Evangelist”.

But three hundred years after the publication of Akrish, when another scholarly enthusiast, the Karaite Abraham Firkovitch, collected a huge number of Jewish manuscripts in his expeditions, the attitude towards the Khazar documents changed. Among these manuscripts, the famous domestic Hebraist Abraham Garkavin discovered another - a lengthy edition of the letter of Tsar Joseph in a manuscript of the 13th century. This meant that the Jewish-Khazar correspondence was not a forgery.

In a lengthy version of his message, Joseph writes that he himself lives on the Itil River near the Gurgan Sea - there was the capital of the kaganate and the wintering quarters of the kaganate, from which, following the traditions of the nomadic nobility, he set off for the summer through the lands of his domain between the Volga and Don rivers . The king enumerates those subject to him " numerous nations"near the Itil River: these are Bur-t-s, Bul-g-r, S-var, Arisu, Ts-r-mis, V-n-n-tit, S-v-r, S-l-viyun. Further, in the description of Joseph, the border of his possessions turns to "Khuvarism" - Khorezm, a state in the Aral Sea region, and in the south it includes S-m-n-d-r and goes to the Caspian gates and mountains. Further, the border follows to the "sea of Kustandin" - "Konstatinople", i.e. Cherny, where Khazaria includes the areas of Sh-r-kil (Sarkel on the Don), S-m-k-r-ts (Tamatarkha - Tmutarakan on Taman), K-r-ts (Kerch), etc. from there the border goes north to the B-ts-ra tribe, which wanders to the borders of the Kh-g-riim region.

Right-bank Tsimlyansk settlement.

Many names of peoples who, according to Josephus, pay tribute to the Khazars, are quite reliably restored and have correspondences in other sources. The first of them - Burtases(Bur-t-s), whose name is sometimes compared with the ethnicon "mordens" (Mordva), mentioned by the Ostrogoth historian of the 6th century. Jordan. However, in the Old Russian "Word of the Destruction of the Russian Land" (XIII century), a strikingly close list of peoples already subject to Rus' is given, where the Burtases are mentioned along with the Mordovians: the borders of Rus' stretch "from the sea to the Bulgarians, from the Bulgarians to the Burtas, from the Burtas to the Chermis , from Chermis to Mordvi". In the context of Joseph's letter, this ethnicon is obviously tied to the Volga region, where the Burtases are followed by the Bulgarians (in Joseph's list - Bul-g-r), and then - S-var, a name that is associated with the city of Suvar in Volga Bulgaria.

Next ethnicon arisu is compared with the self-name of the ethnographic group Mordovians erzya(accordingly, in the Burtases they sometimes see another group of Mordovians - moksha). Name C-r-m-s resonates with chermis ancient Russian source: these are the Cheremis, the medieval name of the Mari, a Finnish-speaking people in the Middle Volga region. The described situation, obviously, dates back to the heyday of the kaganate: in the 60s. In the 10th century, when the letter of Tsar Joseph was compiled, it was hardly possible that the peoples of the Middle Volga region, primarily the Bulgarians who had converted to Islam, depended on the dying kaganate.

The same can be said about the next group of peoples, in which they see the Slavic tributaries of Khazaria. In ethnicon V-n-n-tit usually see the name Vyatichi/Ventichi, who, according to the Russian chronicle, lived along the Oka and paid tribute to the Khazars until the liberation by Prince Svyatoslav during a campaign against Khazaria in 964-965. The next ethnicon - S-v-r - obviously means northerners living on the Desna: they were freed from the Khazar tribute by Prince Oleg, when the Russian princes settled in the Middle Dnieper. The term S-l-viyun, which completes this part of the list of tributaries, refers to common name Slavs. Apparently, here we can mean the whole set of Slavic tributaries, including radimichi And polyan who, according to The Tale of Bygone Years, paid tribute to the Khazars before the appearance Russ in the Middle Dnieper in the 860s. In general, the list of tributaries, therefore, dates back to no later than the second half of the 9th century, rather to the middle of the 9th century, the heyday of the Khazar Khaganate and the construction of white-stone fortresses, including the one mentioned in the Sarkel letter (c. 840).

The legend about the adoption of Judaism by the Khazars explained a lot for historians. Naturally, the kagan did not want to accept Islam: after all, this made him a vassal of the enemy - the Arab caliph. But Christianity did not suit the ruler of Khazaria: after all, he captured the Christian lands of Byzantium. Meanwhile, in the cities of the Caucasus and the Northern Black Sea region, including Phanagoria and Tamatarkh, Jewish communities lived from ancient times, experienced in communicating with the surrounding peoples. These communities also existed in the cities of the Caliphate and Byzantium: Christians and Muslims could communicate with Jews - after all, they were not pagans and revered the one God. The Kagan chose a neutral religion that honored the Holy Scriptures recognized by Christians and Muslims.

Hasdai, however, was an experienced diplomat and understood that the Khazar king was recounting the official legend of the Khazar conversion. Apparently, he turned to another correspondent - a Jew who lived within the boundaries of Khazaria (in Kerch or Taman), who presented the history of the kaganate and the conversion of the Khazars in a slightly different way. It is no longer about an angel who inspired the kagan to accept the true faith - this step of the ruler of the Khazars was vouchsafed by a pious wife from a family of Jewish refugees who escaped persecution in Armenia. This letter was discovered by the English Hebraist Schechter in 1910 in the materials of the largest collection of Jewish manuscripts, which comes from the storage (genizah) of the medieval synagogue in Cairo (Fustat). These materials were transported to Cambridge, and the letter from the anonymous Jew is called the Cambridge Document.

IN modern historiography the perniciousness of the choice of the Jewish faith is usually emphasized: only the Kagan himself and the Khazars accepted Judaism, other peoples retained their "pagan" beliefs. Historians believe that the kagan and the ruling elite of the kaganate were cut off by their faith from other subjects. The reality was still more complicated: if the kagan converted to Islam or Christianity, he would have to forcefully plant a new religion among the tribes and peoples subject to him, but Judaism did not require this.

As a result, an amazing ethno-confessional situation developed in Khazaria: according to the description of al-Masudi, in the Khazar cities, including the capital Itil, different religious communities coexisted side by side: the Jews - the kagan, his commanders bek and the Khazars, who lived in brick buildings, as well as Christians (the Christian population of the Black Sea cities remained among the subjects of the kagan), Muslims (the kagan's guard consisted of Central Asian Oghuz Muslims) and pagans (Slavs and Russia). Each community had its own judges and retained autonomy. This peaceful coexistence of different religious communities was characteristic even for the ancient cities of the Northern Black Sea region and for Constantinople. In Eastern Europe, the establishment of such a tradition was also an important step towards civilization.

However, a strong state pursuing an independent policy at the junction of Europe and Asia could not but arouse opposition from neighboring countries, especially since the Khazars did not leave claims to Byzantine possessions in the Black Sea region and power over the Slavs. In 860, Konstantin (Cyril) the Philosopher himself, the future first teacher of the Slavs, went on behalf of the emperor to the headquarters of the kagan to take part in another dispute about faith: the life of Constantine says that he specifically learned the Hebrew language in Chersonese for this. Obviously, the fate of Christians who found themselves under the rule of Khazaria worried Constantinople.

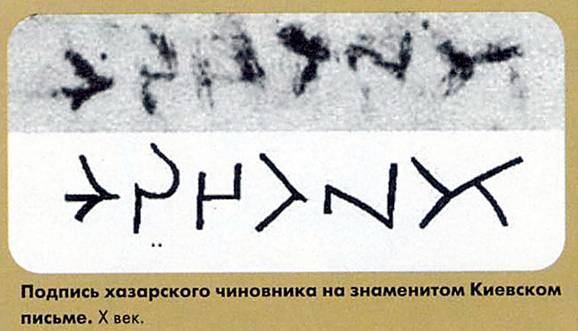

Another recently discovered Jewish document of the 10th century. (read by American Hebraist Norman Golb in 1962)

A letter about a debtor whom the community wants to redeem from debt bondage indicates that

that the Khazar Jews also appeared in the Slavic world.

This document comes from Kyiv and today remains the oldest Russian document.

The signatures of the trustees under this letter are surprising: along with typical Jewish names, a certain

Guests bar Kyabar Kogen.

Guests - Slavic name, known from Novgorod birch bark letters, Kyabar - the name of one of the Khazar tribes,

Cohen - the designation of the descendants of the priestly class among the Jews. Apparently, representatives of this community (one of whom was the son of a Khazarin - kyabara), who probably spoke Slavonic, if they had Slavic names, took part (along with Muslim Bulgarians!) And in a dispute about faith, which took place already under Kiev Prince Vladimir on the eve of the baptism of Rus' in 986

Tsar Joseph in his letter described Khazaria as a powerful state, to which almost all the peoples of Eastern Europe were subordinate, but by the 60s of the 10th century. reality was far from this picture. Already by the beginning of the X century. Islam spread in Volga Bulgaria, and Christianity spread in Alanya: the rulers of these once vassal lands of Khazaria chose their own religion and the path to independence.

Khazaria itself was threatened by new hordes of nomads from the east: the Pechenegs were pushing the Hungarians allied to the Khazars in the Black Sea region (at the end of the 9th century they ended up in Central Europe - present-day Hungary), and the Oguzes were advancing from the Trans-Volga region.

But Rus' became the most dangerous rival of Khazaria in Eastern Europe. Tsar Joseph wrote in his letter: if the Khazars had not stopped the Russians on their borders, they would have conquered the whole world. Rus' really rushed through the territory of Khazaria to the main markets of the Middle Ages - to Constantinople and Baghdad. As already mentioned, Prophetic Oleg with his Varangians and Slavs, nicknamed Rus, captured Kyiv and appropriated the Khazar tribute. In 965, Prince Svyatoslav moved on the last Slavic tributaries of the Khazars - the Vyatichi, who were sitting on the Oka. He subjugated the Vyatichi and went out with an army to the Volga Bulgaria. Rus' plundered the Bulgarian cities and moved down the Volga. The Khazar Khagan was defeated, and his capital city of Itil was taken.

Then Svyatoslav moved to the North Caucasus, to the Alans (yases) and Circassians (kasogs), imposing tribute on them. Apparently, then the Khazar Tamatarkha became a Russian city - Tmutarakan, and the North Caucasus - a "hot spot" of the Old Russian state. On the way back, the prince took Sarkel, which was renamed Belaya Vezha (Slavic translation of the name Sarkel). These Khazar lands came under the rule of Russian princes.

Tsar Joseph turned out to be right in predicting the danger from the peoples whose expansion was held back by Khazaria: the Oguzes seized part of Transcaucasia (forming the ethnic basis of the Azerbaijanis), Svyatoslav's Rus' moved from Kiev to the Balkans, conquering Bulgaria and threatening Byzantium.

The remnants of the defeated Khazars quickly disappeared into this turbulent historical space, which remained the steppes and the North Caucasus. The disappearance of the Khazars, whose mention ceases by the 12th century, gave rise to many romantic and quasi-historical conceptions about their heirs, the Karaites of Crimea. Mountain Jews of the Caucasus - up to brilliant literary hoaxes, including the famous "Khazar Dictionary" by Milorad Pavich. Of particular interest is the attempt of the English writer Arthur Koestler to see in the Khazars, who fled from Eastern Europe, the "thirteenth tribe", the ancestors of European Jews - the Ashkenazim. This historically completely unfounded concept was built on a noble impulse: to prove that anti-Semitism is devoid of any historical foundations - after all, the Khazars were not Semites, but Turks. In fact, European Jews, the ancestors of the Ashkenazim, settled in the X-XII centuries. from the traditional centers of the diaspora in the Mediterranean and knew almost nothing about the Khazars. The culture of the Volga Bulgarians became the most important component of the culture of the Golden Horde. The Volga Bulgarians formed the ethnic basis for the formation of the Chuvash and Kazan Tatars.

Many legends associated with the Khazars are associated with the largest medieval Jewish cemetery in Chufut-Kale. A. Firkovich tried to date some of the monuments to the Khazar time: within the framework of the Khazar project, a complete description of the cemetery is being carried out (A. M. Fedorchuk).

The Khazars suffered the fate of their predecessors, who created their "empires" in Eurasia - the Huns and Turks: with the death of the state, social and ethnic ties were destroyed, and the ruling people also disappeared. But the historical experience of Khazaria turned out to be in demand not only in the Jewish diaspora: it was not for nothing that Vladimir Svyatoslavovich, like his son Yaroslav the Wise, was called the title kagan in the Word of Law and Grace. In the historical sense, Khazaria turned out to be the forerunner not only of the Old Russian, but also of the Russian state as a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional entity. Those beginnings of state, ethnic and confessional development, which were laid down by the Khazars, have survived to this day in Eastern Europe. Ethnic and confessional diversity, coexistence different peoples, religions and cultures remain the key to the further development of our country.

Without pursuing any other goal, as soon as my own whim, according to which, during a walk, I suddenly wanted to combine three poets: A.S. Pushkin, V.S. Vysotsky and A.A. Galich through the prophetic Oleg, either because Providence or fate often occupied their minds and they somehow united in me through this association, or because the first two lines exist in an unchanged state in all three poems by three poets, but one way or another it happened. It seems that it is necessary to say about some distinctiveness in the imagery of these poets. If Pushkin's prophetic Oleg is written without irony and with faith in historical tradition, then Vysotsky's image of the prophetic Oleg is the bearer of a certain life rule, idea, and not a historical event as such. In Galich, the prophetic Oleg is no longer a historical character and not a moralizing idea, but rather a poetic line by Pushkin, transformed into an interpretation of history as such, history in general, and not a prophetic Oleg, and specifically directed against the Marxist approach to antiquity. Below I give all three poems, although A. Galich and V. Vysotsky call them songs and sing, however,

I don't see a significant difference between a song and a poem if there is a logical meaning to the song.

* * *

The circumstances of the death of Prophetic Oleg are contradictory. According to the Kyiv version (“PVL”), his grave is located in Kyiv on Mount Shchekovitsa. The Novgorod chronicle places his grave in Ladoga, but also says that he went "beyond the sea."

In both versions, there is a legend about death from a snakebite. According to legend, the wise men predicted to the prince that he would die from his beloved horse. Oleg ordered the horse to be taken away, and remembered the prediction only four years later, when the horse had long since died. Oleg laughed at the Magi and wanted to look at the bones of the horse, stood with his foot on the skull and said: “Should I be afraid of him?” However, a poisonous snake lived in the horse's skull, which mortally stung the prince.

Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin

Song about the prophetic Oleg

Take revenge on the unreasonable Khazars:

Their villages and fields for a violent raid

He doomed swords and fires;

With his retinue, in Constantinople armor,

The prince rides across the field on a faithful horse.

From the dark forest towards him

There is an inspired magician,

Submissive to Perun, the old man alone,

The promises of the future messenger,

In prayers and divination spent the whole century.

And Oleg drove up to the wise old man.

"Tell me, sorcerer, favorite of the gods,

What will happen in my life?

And soon, to the delight of neighbors-enemies,

Will I cover myself with grave earth?

Tell me the whole truth, don't be afraid of me:

You will take a horse as a reward for anyone."

"Magi are not afraid of mighty lords,

And they do not need a princely gift;

Truthful and free is their prophetic language

And friendly with the will of heaven.

The coming years lurk in the mist;

But I see your lot on a bright forehead.

Now remember my word:

Glory to the Warrior is a joy;

Your name is glorified by victory:

Your shield is on the gates of Tsaregrad;

And the waves and the land are submissive to you;

The enemy is jealous of such a wondrous fate.

And the blue sea is a deceptive shaft

In the hours of fatal bad weather,

And a sling, and an arrow, and a crafty dagger

Spare the winner years ...

Under formidable armor you know no wounds;

An invisible guardian is given to the mighty.

Your horse is not afraid of dangerous labors;

He, sensing the master's will,

That meek stands under the arrows of enemies,

It rushes across the battlefield,

And the cold and cutting him nothing ...

But you will receive death from your horse."

Oleg chuckled - but the forehead

And the eyes were clouded with thought.

In silence, hand leaning on the saddle,

He gets down from his horse sullen;

And a true friend with a farewell hand

And strokes and pats on the neck steep.

"Farewell, my comrade, my faithful servant,

The time has come for us to part;

Now rest! no more footsteps

In your gilded stirrup.

Farewell, be comforted - but remember me.

You, fellow youths, take a horse,

Cover with a blanket, shaggy carpet;

Take me to my meadow by the bridle;

Bathe, feed with selected grain;

Drink spring water."

And the youths immediately departed with the horse,

And the prince brought another horse.

The prophetic Oleg feasts with the retinue

At the ringing of a cheerful glass.

And their curls are white as morning snow

Above the glorious head of the barrow...

They remember days gone by

And the battles where they fought together...

"Where's my comrade?" Oleg said,

Tell me, where is my zealous horse?

Are you healthy? Is his run still easy?

Is he still the same stormy, playful?"

And listens to the answer: on a steep hill

He had long since passed into a sleepless sleep.

Mighty Oleg bowed his head

And he thinks: "What is fortune-telling?

Magician, you deceitful, mad old man!

I would despise your prediction!

My horse would still carry me."

And he wants to see the bones of the horse.

Here comes the mighty Oleg from the yard,

Igor and old guests are with him,

And they see: on a hill, near the banks of the Dnieper,

Noble bones lie;

The rains wash them, their dust falls asleep,

And the wind excites the feather grass above them.

The prince quietly stepped on the horse's skull

And he said: "Sleep, lonely friend!

Your old master has outlived you:

At the funeral feast, already close,

It's not you who will stain the feather grass under the ax

And drink my ashes with hot blood!

So that's where my death lurked!

The bone threatened me with death!"

From dead head coffin snake

Meanwhile, hersing crawled out;

Like a black ribbon wrapped around the legs:

And suddenly the stung prince cried out.

Ladles are circular, foaming, hissing

At the feast of the deplorable Oleg:

Prince Igor and Olga are sitting on a hill;

The squad is feasting at the shore;

Fighters commemorate past days

And the battles where they fought together.

V.Vysotsky

Song about the prophetic Oleg (How the prophetic Oleg is now gathering ...)

How the prophetic Oleg is now going

Shield nailed to the gate,

When suddenly a man runs up to him

And well, lisp something.

"Oh, prince," he says for no reason at all, -

After all, you will accept death from your horse!

Well, he was just about to go to you -

Take revenge on the unreasonable Khazars,

When suddenly the gray-haired magi came running,

In addition, smashing with a fume.

And they say all of a sudden

That he will accept death from his horse.

"Who are you, where did you come from? -

The squad took up the whips. -

Drunk, old man, so go hang out,

And nothing to tell stories

And speak for nothing

"

Well, in general, they did not demolish their heads -

You can't joke with princes!

And for a long time the squad trampled the Magi

With their bay horses:

Look, they say out of the blue,

That he will accept death from his horse!

And the prophetic Oleg bent his line,

Yes, so that no one made a sound.

He only once mentioned the Magi,

And he chuckled sarcastically.

Well, you have to chat for no reason at all,

That he will accept death from his horse!

"And here he is, my horse, - he has rested for centuries,

Only one skull remained! .. "

Oleg calmly laid his foot -

And he died on the spot:

An evil viper bit him -

And he accepted death from his horse.

Each Magi strives to punish,

And if not, listen, right?

Oleg would have listened - another shield

Nailed to the gates of Constantinople.

The Magi said something from this and from this,

That he will accept death from his horse!

1967

Proposed text of my proposed speech at the proposed congress of historians of the countries of the socialist camp, if such a congress were held and if I were given the high honor to make an opening speech at this congress

Alexander Galich

Half the world is in the blood, and in the ruins of the century,

And it was rightly said:

"How is the prophetic Oleg going now

Take revenge on the unreasonable Khazars..."

And these ringing copper words

We repeated everything more than once, not twice.

But somehow from the stands a big man

He exclaimed with excitement and fervor:

"Once the traitor Oleg conceived

Take revenge on our Khazar brothers..."

Words come and words go

Truth follows truth.

Truths are changing, like snow in a thaw,

And let's say that the turmoil ends:

Some Khazars, some Oleg,

For some reason he took revenge!

And this Marxist approach to antiquity

It has long been used in our country,

He was quite useful to our country,

And your country will come in handy,

Since you are also in the same ... camp,

It will come in handy for you!

Reviews

I remembered the same Vysotsky: "And everyone drank not what he brought."

:)

In psychology, the most popular. Perhaps the test is a "non-existent animal", however, there are many similar ones, called projective. An installation is given to draw something, for example, an animal that never existed. A person sniffs, invents something like that, not suspecting that he always draws himself. Deciphering the drawing, it is very easy to tell about the artist)

So. Vysotsky and Galich wrote about themselves.

Pushkin is not about himself.

Because for a fee.

)

Something, Marigold, you wrapped up something almost psychoanalytic, so you can get to the point where you can treat poets and prose writers by interpreting their own works. Oleg, but it was just that the time was such that folk traditions and legends and, in general, the origins of the nation among the people were fashionable. The Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault, Humboldt, etc. etc. As Hegel would say, that first there was the thesis-Pushkin, then the antithesis-Vysotsky, and then the synthesis-Galich. And Kant would add that a priori there was a real historical event and then, apostoriori, the poets made their synthetic judgments.

I read here at leisure that you closed your site, due to the fact that you are no longer able to generalize something meaningful in poetry. I want to note that in poetry you don’t always need to generalize something, but rather express it privately.

"The sound is cautious and deaf,

The fruit that fell from the tree

In the midst of the silent chant

Deep silence of the forest."

O.M.

and he

"Only children's books to read,

Only children's thoughts to cherish,

Everything big is far to scatter,

Rise from deep sadness"

And finally

"And the day burned like a white page,

A little smoke and a little ash"

The ease of being, among other things, consists in the fact that a girl with a white bow does not stand on a chair to tell the guests of her parents the poem she has learned, but goes to school and sings a song that suits her mood.

In the summer of 965, Prince Svyatoslav put an end to the existence of the Khazar Khaganate.

Pushkin knows

How the prophetic Oleg is now going

Take revenge on the unreasonable Khazars:

Their villages and fields for a violent raid

He doomed swords and fires...

Thanks to the "Song of the Prophetic Oleg", written by Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin, the Russians are still in school age learn about the existence of such a people as the Khazars.

But for most acquaintance with the issue ends there. Who the Khazars are, why they are "unreasonable" and whether the claims against them from Prince Oleg were fair - the Russians are rather vaguely aware of this.

Meanwhile, the state of the Khazars was formed much earlier than the ancient Russian one, and the existence of such a concept as the “Khazar world” testifies to its influence. This term refers to the period of dominance in the Caspian-Black Sea steppes of the Khazar Khaganate, which stretched out for almost three centuries.

The Turks who took Tbilisi

As most often happens with ancient peoples, historians have several versions of the origin of the Khazars at once. The most common point of view is that the Khazars originated from a union of Turkic tribes.

Until the 7th century, the Khazars occupied a subordinate position in nomadic empires, but after the collapse of the Turkic Khaganate, they were able to form their own state - the Khazar Khaganate, which lasted more than 300 years.

Initially, the territory of the Khazars was limited to the regions of modern Dagestan north of Derbent, but then it expanded significantly, including the Crimea, the Lower Volga region, Ciscaucasia and the Northern Black Sea region, as well as the steppes and forest-steppes of Eastern Europe up to the Dnieper. IN different time The Khazar Sea was called the Black, Azov and Caspian Seas.

About the Khazars as a separate powerful military force chroniclers mention during the Iranian-Byzantine war of 602–628, during which in 627 the Khazar army, together with the Byzantines, stormed the city of Tbilisi.

These military successes, along with the weakening of the Turkic Khaganate, made it possible to create the Khazar Khaganate. A powerful army became the key to his well-being.

people of war

As a result of numerous military battles, the Khazar Khaganate turned into one of the powerful powers of the era. The most important trade routes of Eastern Europe were in the power of the Khazars: the Great Volga route, the route "from the Varangians to the Greeks", the Great Silk Road from Asia to Europe. For the passage of goods, the Khazars took a tax, which provided a steady income.

The second main source of income for the Khazar Khaganate was the receipt of tribute from the tribes conquered in the course of regularly carried out raids.

Initially, the main direction of the Khazar raids was Transcaucasia, but then, under the pressure of the ever-increasing Arab Caliphate, the Khazars began to move north, where their raids affected the Slavic tribes. Whole line Slavic tribes, which later formed the Old Russian state, were forced to pay tribute to the Khazars.

In the VIII century, the Khazars, having entered into a coalition with the Byzantine Empire, waged wars against the gaining strength of the Arab Caliphate. In 737, the Arab commander Marwan ibn Muhammad, at the head of a 150,000-strong army, completely defeated the army of the Khazar Khaganate, pursuing its ruler up to the banks of the Don, where the Khagan was forced to promise to convert to Islam. And although the complete transition of the Khazar Khaganate to Islam did not take place, this defeat seriously affected further development states. Dagestan, where the capital of the kaganate, the city of Semender, was previously located, turned into the southern outskirts, and the center of the state moved to the lower reaches of the Volga, where it was built new capital- city of Itil.

Jews from the banks of the Volga

Until the middle of the 8th century, the Khazars remained pagans. However, around 740, one of the prominent Khazar commanders, Bulan, converted to Judaism. This happened, apparently, under the influence of numerous Jewish communities living at that time in the "historical territory" of the Kaganate - in Dagestan.

Over time, Judaism became widespread among the ruling elite of the Khazar Khaganate, however, according to most historians, it did not completely become a state religion. Moreover, part of the military and commercial elite of the state opposed the ruling elite, which led to confusion and political instability.

Since the beginning of the 9th century, a kind of dual power has developed in the Khazar Khaganate - nominally the country was headed by khagans from a royal family, but the real control was carried out on their behalf by "beks" from the Bulanid clan that converted to Judaism.

It was difficult to envy the Khagans of Khazaria because of the peculiar traditions that existed among this people at the time of paganism. Despite the fact that the kagan was considered the earthly incarnation of God, when he ascended the throne, he was strangled with a silk cord. Brought to a semi-conscious state, the kagan had to name the number of years during which he would rule. After this period, the kagan was killed. Saying too many years also did not save - in any case, the kagan was killed when he reached the age of 40, because it was believed that by this time he was beginning to lose his divine essence.

Farmers versus nomads

Despite cruel morals and a religion not the most common in the region, adopted by the elite, the Khazar Khaganate remained an important player in international politics.

The Khazars actively interacted with Byzantium, participated in the political intrigues of the empire, and in 732 the allied relations of the powers were sealed by the marriage of the future emperor Constantine V with the Khazar princess Chichak.

The Khazars left a particularly deep trace in the history of the Crimea, which was under their control until the middle of the 9th century, as well as in Taman, which the kaganate controlled until its fall.

A clash between the Old Russian state and the Khazar Khaganate was inevitable. Simplistically, it can be imagined as a confrontation between settled farmers and nomadic invaders.

The Old Russian state was faced with the fact that part of the Slavic tribes turned out to be tributaries of the Khazars, which categorically did not suit the Russian princes. In addition, the regular raids of the Khazars led to the destruction of the settlements of the Russians, robberies, the withdrawal of thousands of Slavs into captivity and their subsequent sale into slavery.

In addition, the control of the Khazars over trade routes prevented the communication of the Rus with other states, as well as the establishment of mutually beneficial trade relations with other countries.

The Khazars could not refuse raids on the territory of the Slavic tribes, since robberies and the slave trade by the 9th century turned into the most important article state income.

The first fighters against the "Russian threat"

In 882, Oleg became prince of Kyiv. Having gained a foothold in Kyiv, he begins to conduct methodical work to expand the territory of the state. First of all, he is interested in the Slavic tribes that are not controlled by Kyiv. Among them were those who were tributaries of the Khazars. In 884 and 885, the northerners and Radimichi, who had previously paid tribute to the Khaganate, recognized Oleg's authority. Of course, the Khazars tried to restore the status quo, but they no longer had enough strength to punish Oleg.

During this period, the Khazars, more sophisticated in diplomacy, tried to transfer the "Russian threat" to Byzantium or the states of Transcaucasia, ensuring the unimpeded passage of the Russian troops through their possessions.

True, and here it was not without deceit. An episode that occurred after the return of the Russians after one of these expeditions to the coast of Azerbaijan is indicative. The ruler of the Khazar Khaganate, having received a previously agreed part of the booty, allowed his guard, formed from Muslims, to avenge their fellow believers. As a result, most of the Russian soldiers died.

The struggle of the Old Russian state with the Khazar Khaganate continued with varying success until Prince Svyatoslav Igorevich came to power. One of the most warlike princes of Ancient Rus' decided to put an end to the Khazar raids once and for all.

Around 960, the Khazar Khagan Joseph, in a letter to the dignitary of the Cordoba Caliphate, Hasdai ibn Shafrut, noted that he was waging a “stubborn war” with the Rus, not letting them into the sea and overland to Derbent, otherwise they, according to him, could conquer all Islamic lands to Baghdad. At the same time, Joseph was sure that he was able to fight for a long time.

And then Svyatoslav came ...

In 964, during a campaign to the Oka and the Volga, Svyatoslav freed from Khazar dependence last union Slavic tribes - Vyatichi. At the same time, it is worth noting that the Vyatichi did not want to obey Kyiv either, which resulted in a series of wars stretching for many years.

In 965, Svyatoslav with an army moved directly to the territory of the Khazar Khaganate, inflicting a crushing defeat on the troops of the Khagan. Following this, the Russians stormed the Sarkel fortress built on the banks of the Don with the help of Byzantium. The settlement came under the authority of the Old Russian state and received a new name - Belaya Vezha. Then the city of Samkerts on the Taman Peninsula was taken, which turned into the Russian Tmutarakan.

Over the next few years, Svyatoslav's army captured both capitals of the Khazar Khaganate - Itil and Semender. An end was put in the history of the once mighty state.

After Svyatoslav, the Russians retreated from the lower Volga for some time, which allowed the exiled kagan of Khazaria to return to Itil, relying on the support of the Islamic ruler of Khorezm. The payment for this support was the conversion of the Khazars to Islam, including the head of state himself.

However, this could not change the course of history. In 985, the Russian prince Vladimir again set off on a campaign against the Khazars and, having won a victory, imposed tribute on them.

From that moment on, the Khazars appear in historical annals not as representatives of a single power, but as small groups acting as subjects of other countries. Gradually, the Khazars dissolved among other, more successful peoples.

And in memory of the “first enemy of Russia”, we were left with only historical works and Pushkin’s lines about the “unreasonable”, with whom the prophetic Oleg intended to “revenge”.

PS The Khazar fortress Sarkel, aka Belaya Vezha, was planned to be flooded in 1952 during the construction of the Tsimlyansk reservoir.

660 YEARS TOGETHER AND 50 YEARS OF LIES

“How Prophetic Oleg is now going to take revenge on the unreasonable Khazars ...” Usually, it is precisely these Pushkin lines that limit all acquaintance of modern Russians with the history of Russian-Khazar relations, which goes back about 500 years.

Why did it happen so? In order to understand this, we need first of all to remember what these relationships were like.

KhAZARS AND Rus'

The Khazar Khaganate was a gigantic state that occupied the entire Northern Black Sea region, most of the Crimea, the Sea of \u200b\u200bAzov, the North Caucasus, the Lower Volga region and the Caspian Trans-Volga region. As a result of numerous military battles, Khazaria became one of the most powerful powers of that time. The most important trade routes of Eastern Europe were in the power of the Khazars: the Great Volga route, the route "from the Varangians to the Greeks", the Great Silk Road from Asia to Europe. The Khazars managed to stop the Arab invasion of Eastern Europe and restrain the nomads rushing to the west for several centuries. The huge tribute collected from numerous conquered peoples ensured the prosperity and well-being of this state. Ethnically, Khazaria was a conglomerate of Turkic and Finno-Ugric peoples who led a semi-nomadic lifestyle. In winter, the Khazars lived in cities, in the warm season they wandered and cultivated the land, and also staged regular raids on their neighbors.

At the head of the Khazar state was a kagan, who came from the Ashina dynasty. His power rested on military force and on the deepest popular reverence. In the eyes of ordinary pagan Khazars, the kagan was the personification of God's power. He had 25 wives from the daughters of rulers and peoples subject to the Khazars, and 60 more concubines. Kagan was a kind of guarantee of the well-being of the state. In the event of a serious military danger, the Khazars brought out their kagan in front of the enemy, the mere sight of which, it was believed, could put the enemy to flight.

True, in case of any misfortune - military defeat, drought, famine - the nobility and the people could demand the death of the kagan, since the disaster was directly associated with the weakening of his spiritual power. Gradually, the power of the kagan weakened, he became more and more a "sacred king", whose actions were fettered by numerous taboos.

Approximately in the 9th century in Khazaria, real power passes to the ruler whose sources title it differently - bek, infantry, king. Soon there are deputies and the king - kundurkagan and dzhavshigar. However, some researchers insist on the version that these are only the titles of the same kagan and king...

For the first time, Khazars and Slavs clashed in the second half of the 7th century. It was a counter movement - the Khazars expanded their possessions to the west, pursuing the retreating Proto-Bulgarians of Khan Asparuh, and the Slavs colonized the Don region. As a result of this clash, quite peaceful, judging by the data of archeology, part of the Slavic tribes began to pay tribute to the Khazars. Among the tributaries were glades, northerners, radimichi, vyatichi and the mysterious tribe “s-l-viyun” mentioned by the Khazars, which, perhaps, were the Slavs who lived in the Don region. The exact size of the tribute is unknown to us; various information on this subject has been preserved (squirrel skin "from the smoke", "slit from the ral"). However, it can be assumed that the tribute was not particularly heavy and was perceived as a payment for security, since there were no recorded attempts by the Slavs to somehow get rid of it. It is with this period that the first Khazar finds in the Dnieper region are associated - among them the headquarters of one of the kagans was excavated.

Similar relations persist after the adoption of Judaism by the Khazars - according to various dates, this happened between 740 and 860. In Kyiv, which was then a border town of Khazaria, around the 9th century, a Jewish community arose. A letter about the financial misadventures of one of its members, a certain Yaakov bar of Hanukkah, written at the beginning of the 10th century, is the first authentic document reporting the existence of this city. The researchers were most interested in two of the nearly a dozen signatures under the letter - "Judas, nicknamed Severyata" (probably from the tribe of northerners) and "Guests, son of Kabar Cohen." Judging by them, among the members of the Jewish community of Kyiv there were people with Slavic names and nicknames. It is highly probable that they were even Slavic proselytes. At the same time, Kyiv received a second name - Sambatas. This is the origin of this name. The Talmud mentions the mysterious Sabbath river Sambation (or Sabbation), which has miraculous properties. This turbulent, rock-rolling river is utterly impassable on weekdays, but with the onset of Sabbath rest time, it calms down and becomes calm. Jews living on one side of the Sambation cannot cross the river, as this would be a violation of Shabbos, and can only talk with their fellow tribesmen on the other side of the river when it calms down. Since the exact location of the Sambation was not indicated, members of the outlying Kyiv community identified themselves with those same pious Jews.

The very first contact between the Khazars and the Rus (by the name "Rus" I mean numerous Scandinavians, mostly Swedes, who rushed at that time in search of glory and prey) falls on the beginning of the 9th century. The latest source - "The Life of Stefan of Surozh" - records the campaign of the "Prince of the Rus Bravlin" on the Crimean coast. Since the path “from the Varangians to the Greeks” was not yet functioning, most likely Bravlin followed the then established path “from the Varangians to the Khazars” - through Ladoga, Beloozero, the Volga and the transfer to the Don. The Khazars, occupied at that moment by the civil war, were forced to let the Rus pass. In the future, the Rus and Khazars begin to compete for control of the trans-Eurasian trade route that passed through the Khazar capital of Itil and Kyiv. Mostly Jewish merchants, who were called "radanites" ("knowing the way"), cruised along it. The Russian embassy, taking advantage of the fact that a civil war was blazing in Khazaria, arrived in Constantinople around 838 and offered an alliance to the Byzantine Emperor Theophilus, who ruled in 829-842. However, the Byzantines preferred to maintain an alliance with the Khazars, having built for them the Sarkel fortress, which controlled the route along the Don and the Volga-Don portage.

Around 860, Kyiv emerged from the Khazar influence, where the Russian-Varangian prince Askold (Haskuld) and his co-ruler Dir settled. According to the deaf references preserved in the annals, it can be established that it cost Askold and Dir a lot - for almost 15 years, the Khazars, using mercenary troops consisting of Pechenegs and the so-called "black Bulgarians" who lived in the Kuban, tried to return Kiev. But he was lost forever. Around 882, Prince Oleg, who came from the north, kills Askold and Dir and captures Kyiv. Having settled in a new place, he immediately begins the struggle for the subjugation of the former Khazar tributaries. The chronicler impassively records: in 884 " go Oleg to the northerners, but defeat the northerners, and lay tribute to the light, and will not give them tribute to pay tribute". In the following year, 885, Oleg subordinated the Radimichi to Kyiv, forbidding them to pay tribute to the Khazars: “... do not give a goat, but give me. And vzasha Olgovi according to shlyag like and Kozaro dayah". The Khazars respond to this with a real economic blockade. Hoards of Arab coins, found in abundance on the territory of the former Kievan Rus, testify that approximately in the middle of the 80s of the 9th century, Arab silver ceased to flow to Rus'. New hoards appear only around 920. In response, the Rus and the Slavic merchants subordinate to them are forced to reorient themselves towards Constantinople. After Oleg's successful campaign against Byzantium in 907, peace and a treaty of friendship are concluded. From now on, caravans of Russian merchants annually arrive in the capital of Byzantium. The path "from the Varangians to the Greeks" was born, becoming the main one for trade relations. In addition, the Volga Bulgaria lying at the confluence of the Volga and Kama is flourishing, intercepting the role of the main trading intermediary from the Khazaria. However, the latter still remains a major trading center: merchants from many countries come to Itil, including the Rus, who live in the same quarter with the rest of the “sakaliba”, as the Slavs and their neighbors were called in the 10th century, for example, the same Volga Bulgars .

However, sometimes not only merchants appear. A few years after Oleg's campaign against Byzantium, most likely around 912, a huge army of the Rus, numbering almost 50,000 soldiers, demands from the Khazar king to let them through to the Caspian Sea, promising half of the booty for this. The king (some historians believe that it was Benjamin, the grandfather of Joseph, the correspondent of Hasdai ibn Shaprut) agreed to these conditions, unable to resist, since several vassal rulers rebelled against him at that moment. However, when the Rus returned and, according to the agreement, sent the king his half of the booty, his Muslim guards, who may have been on the campaign at the time of the conclusion of the agreement, suddenly became indignant and demanded permission to fight the Rus. The only thing the king could do for his recent allies was to warn them of the danger. However, this did not help them either - almost the entire army of the Rus was destroyed in that battle, and the remnants were finished off by the Volga Bulgars.

It may be that it was in that battle that Prince Oleg also found his death. One of the chronicle versions of his death reads: Oleg died "beyond the sea" (about the possible causes of several versions of the death of this statesman we will discuss below). For a long time, this episode was the only one that overshadowed the relations between Khazaria and Kievan Rus, headed by the Rurik dynasty. But in the end, thunder struck, and it was the Byzantines who apparently decided to transfer the title of their main ally in the region to someone else. Emperor Romanus Lekapinus, who usurped the throne, decided to raise his popularity by persecuting the Jews, whom he ordered to force to be baptized. For his part, the Khazar king Joseph, it seems, also carried out an action against disloyal, in his opinion, subjects. Then Roman persuaded a certain “king of the Rus” Kh-l-gu to attack the Khazar city of Samkerts, better known as Tmutarakan. (This is about the campaign against the Khazars of the Prophetic Oleg.) The revenge of the Khazars was truly terrible. The Khazar commander Pesakh, who bore the title, which various researchers read as Bulshtsi or "Balikchi", at the head of a large army, first ravaged the Byzantine possessions in the Crimea, reaching Kherson, and then headed against Kh-l-gu. He forced the latter not only to hand over the loot, but also to set off on a campaign against ... Roman Lekapin.

This campaign, which took place in 941 and is better known as the campaign of Igor Rurikovich, ended in complete failure: the boats of the Rus met ships throwing the so-called "Greek fire" - the then miracle weapon, and sank many of them. The landing force, which ravaged the coastal provinces of Byzantium, was destroyed by the imperial troops. However, Igor's second campaign, which took place around 943, ended more successfully - the Greeks, without bringing the matter to a collision, paid off with rich gifts.

In the same years, a large army of Russ reappeared on the Caspian Sea and captured the city of Berdaa. However, the uprising of the local population and epidemics led to the failure of this campaign.

It would seem that from the moment of Kh-l-gu's campaign, relations between the Rus and Khazaria are completely spoiled. The next news about them refers to approximately 960 - 961 years. The Khazar king Joseph in a letter to the court Jew of the Cordoba Caliph Abd-arRahman III Hasday ibn Shaprut categorically states that he is at war with the Rus and does not allow them to pass through the territory of his country. “If I had left them alone for one hour, they would have conquered the entire country of the Ismailis, all the way to Baghdad,” he emphasizes. However, this statement is contradicted both by the information reported by Hasdai himself - his letter to Joseph and the latter's answer proceeded through the territory of Rus' - and by the numerous mentions of the authors of the general Russian colony in Itil. Both powers are likely to maintain mutual neutrality and try on a future fight.

It turns out to be associated with the name of Prince Svyatoslav of Kyiv. Most researchers agree that the main reason for the campaign against Khazaria was the desire of the Kiev prince to eliminate the very burdensome Khazar mediation in the eastern trade of the Rus, which significantly reduced the income of merchants and the feudal elite of Kievan Rus, closely associated with them. Thus, The Tale of Bygone Years records under the year 964: “And [Svyatoslav] went to the Oka river and the Volga and climbed the Vyatichi and said to the Vyatichi: “To whom do you give tribute?” They decide: “We give Kozaram a shlyag from the ral.” In the entry under the year 965, it is noted: “Svyatoslav went to the goats, hearing the goats from the dosha against his prince Kagan and stepping down, he beats and used to fight, overcoming Svyatoslav the goat and taking their city of Bela Vezha. And defeat the yas and kasog. Record for 966: "Vyatichi defeat Svyatoslav and pay tribute to them." Combining chronicle references, information from Byzantine and Arab authors, and archaeological data, one can imagine the following picture. The Rus army, which came from Kyiv, or possibly from Novgorod, wintered in the land of the Vyatichi. In 965, the Russians, having built boats, moved down the Don and somewhere near Sarkel (annalistic Belaya Vezha) defeated the Khazar army. Having occupied Sarkel and continued his campaign down the Don, Svyatoslav subjugated the Don Alans, known as Ases-Yases. Having entered the Sea of Azov, the Rus crossed it and captured the cities on both banks of the Kerch Strait, subjugating the local Adyghe population or making an alliance with it. Thus, an important segment of the path “from the Slavs to the Khazars” passed under the control of the Kievan prince, and burdensome duties were probably reduced by the Khazars after the defeat.

In 966, Svyatoslav returned to Kyiv and never returned to the Don region again, turning his attention to Bulgaria. Returning from there, he died in 972. Thus, the Khazar Khaganate had a chance not only to survive, but also to regain its former power.

Unfortunately, trouble never comes alone. In the same year 965, the Guzes attacked Khazaria from the east. The ruler of Khorezm, to whom the Khazars turned for help, demanded conversion to Islam as a payment. Apparently, the position of the Khazars was so desperate that all of them, except for the kagan, agreed to change their faith in exchange for help. And after the Khorezmians drove away the "Turks", the Khagan himself accepted Islam.